| More about: | International Atomic Energy Agency, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Harry S. Truman |

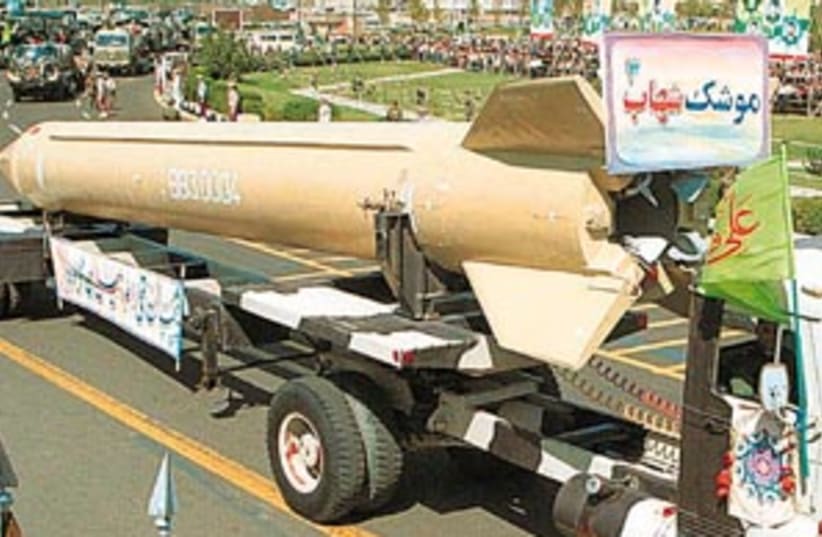

Storm clouds gathering

Iran's nuclear defiance may be forcing Israel towards a showdown.

| More about: | International Atomic Energy Agency, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Harry S. Truman |