We waited the requisite 10 minutes after the last “Boom!” and then climbed back up the stairs to our apartment. I congratulated them on their bravery while I changed Eitan’s pajamas and tucked them back into their beds. Then I went into the living room, fell onto the couch, and burst into tears. Then I couldn’t have known that this scene would repeat itself countless times over the 28 days that followed.

The phone rang. It was my husband Moshe, calling from Switzerland, on a business trip. “Are you ok?” he asked. “Yes,” I said. “I have good news and bad news,” he said. Whenever he said that I knew it was really just bad news. “The good news is I am getting on a flight now and I will be home in a few hours.”

“And the bad news?” “I won’t be able to stay very long. I have been called up.”

Moshe arrived at 3 a.m. Dropped his suitcases and picked up his army duffel. Changed into fatigues. Kissed the kids. Kissed me. And walked out the door.

The next day Eitan and Noa’s summer camp announced that they were closing, as they didn’t have an adequate bomb shelter. The kids and I found ourselves at home with limited options. There was a shelter at the nearby playground. I estimated that we could make it to the shelter under our building or to the one at the playground from any point in between within 90 seconds, which is the amount of time it takes for a rocket fired from the Gaza Strip to land in the Greater Tel Aviv area.

I couldn’t comprehend the measly 7-15 second deadline for the citizens of Sderot and other Israeli towns bordering the Gaza Strip, who had lived with a constant stream of rockets for more than 10 years.

Moshe’s parents, Saba and Safta’s house was also an option. But even the 10-minute drive was nerve-wracking. If the siren went off, I would get the kids out of the car and cover them with my own body to protect from falling shrapnel. The thought of this was too traumatizing to risk for a change of scenery. It would be my last resort only if the kids got too stir-crazy.

Of course, after a few days between home and the playground, the kids did go stir crazy, so we ventured out to Saba and Safta’s house, where we stayed for five days. They helped tremendously, entertaining the kids, calming me with their lifetimes of experience in such wars, and helping to carry the kids down to the bomb shelter when a rocket siren, or “piyu”, as the kids began to call them, went off.

After four nights, I decided it was time to return home and in my state of panic to be between shelters, ended up in a fender bender, bumping the car in front of me. I got out of the car. “Are you OK?” I asked the woman who I had hit before bursting into tears. She put her arms around me. “I see you’re not OK.”

“I’m so sorry,” I sobbed. “It’s this situation. I’m so nervous.” We exchanged information quickly. “It’s okay, darling,” she said. “Everyone is nervous now. We will get through this. You will get through this. It’s all part of being Israeli.” It was the first of three fender-benders I got into during the war.

It turns out our local pool had a shelter, so that became an option. I would just have to drive two minutes to get there. We went to the pool almost every day. We had many “piyus” there. Each time, I scooped up the kids– their little hands losing their grasp on the toy they were playing with poolside, or the ice cream cone they were eating – and ran down to the shelter. Each time, the two of them burrowed into me.

I tried to make the time at home as fun for them as I could. Whenever Safta came for a few hours, I rushed out to the local market to pick up food and always brought back big paper and paint, new coloring books, videos, puzzles, stickers. I pitched a little tent for them in the living room and the two of them started to play a game where one would shout “Piyu!” then both would run into the tent. The first time they played that game I went to the bathroom and cried.

It was the kids, and spending time with them, that kept me in one piece. Without them I would fall apart. Which I did. Every night after they went to bed. Then my mind could wander, undistracted, to Moshe.

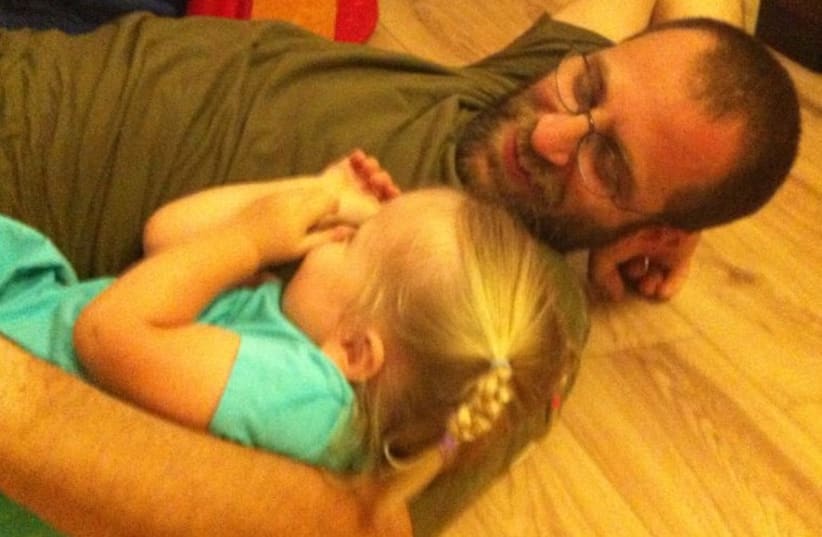

My Moshe, who feeds and waters the street cats. My Moshe, who turns the kids upside-down to make them giggle. My Moshe, who has endless patience for my shenanigans, who makes me laugh a dozen times a day and kisses me when (he thinks) I’m sleeping. My Moshe was there, somewhere, in Gaza.

Every night after the kids went to bed I sat up with my laptop, compulsively refreshing the news. Every time a soldier was killed or injured I panicked and called Moshe’s dad, no matter the hour. “What if…?”

“You have to relax, Jenny. You have to have faith,” came his familiar response. But I couldn’t relax. I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t do anything but wait. And refresh. Until finally they published the name. Then I’d cry while I read about the soldier who died and the family that had been blown apart. But who was not, thank G-d, my Moshe.

He was without his phone. Only a few times, in 28 days, did I receive some sort of update. Once or twice it was Moshe, or one of his soldiers, or the wife of one of his soldiers. When I did hear from him, it was a short conversation or a text message. Just long enough for me to know he was alive. As soon as I got a message, I called everyone – his parents, his siblings, my parents in Canada, his friends, and the other soldiers’ wives, who, like me, were waiting to breathe between signs of life.

Once, near the end of the operation, Moshe was able to Skype with us for a few minutes. Until then, Eitan had barely mentioned Moshe in his absence. Noa, on the other hand, talked about Moshe constantly. Every morning she ran to our bed looking for Abba and every night she lulled herself to sleep with the mantra, “Abba, Abba, Abba”. When Moshe’s face appeared on Skype, Eitan wailed, “ABBA!” He couldn’t stop crying. He was inconsolable.

While the war gripped our little family in emotional throws, another war raged on - in the press, on Facebook and in email chains, among my closest friends and family. At best, they had a remote academic take on the conflict; at worst, an oversimplified regurgitation of the foreign news. Both begged to be contested.

And contest I did. I defended Israel’s right to defend itself against the constant slew of rocket attacks and the construction of tunnels built to murder our civilians. We were fighting because we had no other choice; because our lives were being threatened.

I stood by the IDF’s devastating but necessary destruction of buildings in Gaza – the tragic ruin of homes, schools, hospitals, and even UNWRA facilities, which Hamas militants used to shelter their operatives, weapons, and tunnels, thereby putting civilians strategically in front of military targets and sacrificing innocent Palestinians in order to raise the world’s ire against Israel.

Two million Palestinian people are suffering unspeakable losses at the behest of 12,000 militant thugs who run the Gaza Strip like the Mafia, oppressing, intimidating, brainwashing and murdering them for suspected “treason”. Instead of building bomb shelters for their people, Hamas leadership built terror tunnels into Israel. While these terrorists lined their own pockets with funds from their oil-rich Israel-hating supporters - at the top of Hamas are 1,700 millionaires - the Gazan GDP per capita rings in at an abysmal $876 (in Canada it’s $52,177).

The Palestinians are victims. They are victims of the IDF, but only as a byproduct of victimization by their own leadership; a leadership whose declared intention is to wipe Israel off the map, and who initiated and refused to stop launching rockets and building tunnels to kill Israelis. Hamas started a war with Israel, then pushed Palestinian civilians to the front lines.

Contrary to popular belief, we in Israel grieve for the Palestinians. We know that our suffering is nothing compared to theirs. We value all human life. We treat Palestinians in our hospitals and set up field hospitals on the Gaza border to treat injured Gazans. Since the start of this war, Israel’s COGAT agency has sent a total of 4,191 trucks of humanitarian aid into Gaza. We mourn the Palestinian civilian losses as we mourn our own.

We didn’t want to send our husbands, our sons, our brothers, to fight in Gaza. We didn’t want to pay the $20,000 per Iron Dome interception. We are not a people who want war, and we certainly didn’t want this one.

I denounced the foreign media for incorrectly terming the war a “genocide”; for being intimidated into silence by Hamas; for not doing due diligence on the casualty numbers tallied by the Hamas-run Palestinian Ministry of Health; for their reductive and incorrect assumption that moral equivalency can be drawn by number of civilian casualties (of course Palestinians have more casualties, because Hamas uses them as human shields. Israel’s numbers, on the other hand, are low because of the Iron Dome, a miracle piece of locally-developed technology that Israel shouldn’t have to apologize for using); and finally, for misleading the public with an oversimplified and inaccurate version of the conflict that reduces it to some sort of amorphous Israeli aggression versus an equally amorphous Palestinian victimization.

I railed against the idea of “proportional response”. What is a proportional response to terrorists launching rockets in a continual stream into Israel's most densely populated civilian centers?

I decried the United States’ $11 billion weapons deal with Qatar, and laughed off US Scertary of State John Kerry’s untenable Qatar and Turkey–brokered ceasefire propositions (the former being one of Hamas’ primary funders, the latter a supporter of the Muslim Brotherhood). I was appalled at US President Barack Obama’s lukewarm public support for Israel. Where was our greatest ally in our time of need?

My various defenses cost me a 20-year-friendship, when a very close friend of mine from Toronto said we had irreconcilable differences of political opinion given Moshe’s participation in the IDF and my support of it.

That was the last straw. I was trying to hold back a tidal wave and my arms were tired. I stopped defending. I stopped commenting. I stopped caring what anyone outside of Israel had to say about the war.

I decided that until they had a violent population of terrorists launching rockets and building tunnels under their houses, intent on ambushing and murdering them; until they had a husband who left to fight, and whose absence traumatized their children and ate them up with worry so that they couldn’t sleep or eat for a month; until they had 90 seconds to drag their kids into a bomb shelter at 3 am; until they lived in a country that is threatened, existentially, by hostile neighbors, I would not be compelled to justify Israel’s actions.

And then, just like that, I got a call on August 4 from Moshe’s phone. It was Day 28. He was finally coming home.

All three of us jumped on him when he walked through the door. For days, Noa ran around the house giggling and shrieking “Abba! Abba! Abba!” Finally, I could breathe again. Our family was reunited and we were happy.

Moshe returned from Operation Protective Edge with some surprising stories. The kind you don’t read about in the news. Like how his unit altered plans in their sector to minimize potential damage to property.

Or his soldiers’ sadness at the abandoned Palestinian homes. Nearby one of their military positions was an abandoned house. The residents had left behind a few chickens, sheep, and goats. Every day the soldiers were at that position, on their own initiative they did what they called “farm chores”. They came out from their cover, endangering their lives, to feed and water the animals.

The IDF developed a system for tanks called “Trophy” that senses when anti-tank missiles are launched at the tank and, as a countermeasure, blows up the missile before it hits the tank. Subsequently, the system automatically turns the tank’s gun toward the place it identifies as the missile’s launching spot (it doesn’t fire automatically, of course). On many occasions, Moshe’s tanks automatically redirected to mosques.

He’s full of stories like these.

We will never be the same again after these 28 days. Not Moshe. Not me. Not Eitan. Not Noa. I cannot know the long-term impact this experience will have on us. Every time I hear a motorcycle rev its engine (which sounds uncannily like the start of the rocket siren) my stomach jumps into my throat. Every time I take Noa down the stairs in our building she turns to me and asks “Piyu?” I can’t begin to imagine what this war has done to Moshe.

No Israeli will be the same again. We will add these scars to the others we have collected over the years, throughout the wars. These scars remind us that we have neighbors who fantasize about our death in ways we cannot begin to understand; that we could find ourselves in a situation where those who we think are our best friends can turn their backs on us.

They also remind us to be grateful that we were born to a people that love life, rather than to a people that celebrate death. They remind us that we have been strong. And we can be strong again. They remind us that even if we don’t have anyone else, we have each other. From the teenage girls next door who came to our apartment to help me with the kids whenever a siren went off instead running straight to the bomb shelter to the stranger who hugged me after I crashed into her car, to the in-laws whose support deepened my love for them, to the soldiers who lost or risked their lives for my safety. We in Israel have each other. And that is really enough.Jenny Hazan made aliya from Canada in 2001.