In 1991, pianist Ellis Marsalis sent me a letter that I’ve held onto ever since.

In fact, I framed it, so that I would see it every day, to remind myself of what he wanted me to know.

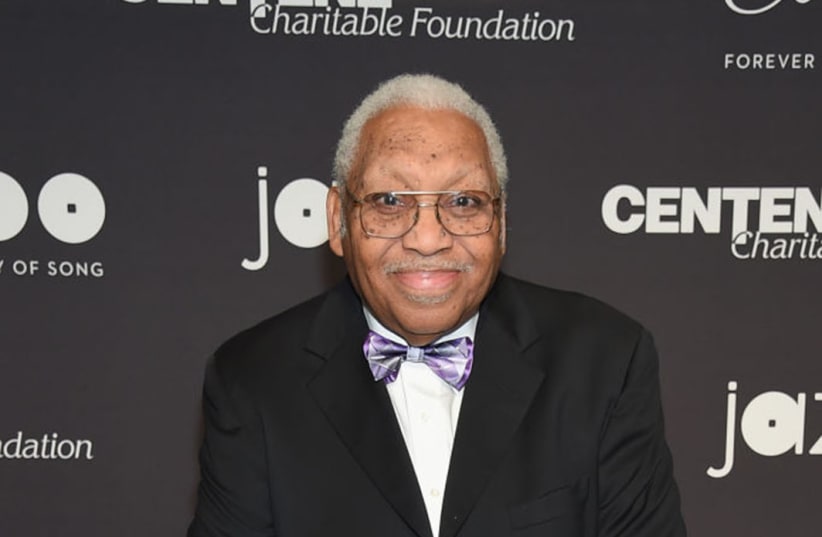

Marsalis, who died April 1 at age 85 of complications of the coronavirus, told me that I should “keep up the good work” so that others “may recognize you as a significant model of jazz criticism.”

But it occurs to me now, as the jazz world mourns one of its most revered elders, that in those words the eminent musician encapsulated what he himself had spent a lifetime doing – at significant personal cost. For he had served as a model for what jazz is and ought to be, and how we shouldn’t lower our standards to suit popular tastes and fashions.

He certainly didn’t. In the 1960s, when Ellis L. Marsalis Jr. – his full name – was emerging as a pianist and saxophonist, the jazz world he aspired to enter was imploding. Youth-oriented rock music was destroying everything in its path in the marketplace, and extraordinarily accomplished jazz musicians were finding clubs closing, record labels shuttering or shunning them, the broader audience turning away.

None of which escaped Marsalis’ notice, nor deterred him from a life in jazz.

“Let’s put it this way – there wasn’t much work you could get, except maybe on the Fourth of July and Christmas,” he told me in a 1991 interview.

So Marsalis supported his family playing assorted dives, touring with trumpeter Al Hirt, taking low-paying teaching gigs and otherwise subsisting in a jazz world that was crumbling around him.

“It was rough on daddy all the way,” trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, one of Ellis and Dolores Marsalis’ six sons, told me that year. “There was hardly anyplace to play the music. And it wasn’t easy sitting behind screens on buses.”

Meaning that in addition to the economic hardship of the jazz life, there was the brutal weight of pervasive racism.

“We went to a Catholic school with 1,500 kids in which 20 were black, and it was strange,” saxophonist Branford Marsalis, another Marsalis son, told me at the time.

“The teachers weren’t openly hostile, but their ignorance was even more detrimental to us than if they had been. To them, (N-word) was an accepted part of the English language.”

Against this backdrop, Ellis Marsalis pushed forward, refusing to compromise his art or aspirations. Instead, he and his wife developed a strategy that appears to have influenced their high-achieving sons and the generations of jazz musicians who followed his artistic lead.

“They taught us that whatever you do, if you’re not going to be the best, don’t do it,” trombonist Delfeayo Marsalis, another son, told me in 1991. “That was how you survived – by being the best.

“And we did it with music because of my dad.”

LONG BEFORE the Marsalis name became internationally known – thanks to the acclaim won by the Marsalis progeny – Ellis Marsalis toiled for small change while creating great art.

You could hear it on several superb but little-heralded recordings, such as Solo Piano Reflections, a 1978 album he reissued as a CD on his own label, ELM Records. The recording shows that at an early stage in his career, Marsalis was embracing the influence of the greatest of all jazz pianists, Art Tatum. The running scales, florid arpeggios and other technically expansive devices affirmed Marsalis’ virtuosity, while his profoundly lyrical playing in John Lewis’ Django and Chick Corea’s Spain illuminated the substance beneath the glitter.

His 1997 reissue of his 1983 recording Syndrome: Ellis Marsalis (ELM Records), attested to the man’s harmonic adventurousness and orchestral conception in a small-group setting, with bassist Bill Huntington, drummer James Black and flutist Kent Jordan.

But over time, like many great artists, Marsalis distilled his work to its essence, in his case via carefully chosen notes and succinctly stated gestures. That was apparent in 2008’s An Open Letter to Thelonious (ELM Records), with its tough and unvarnished approach to Monk landmarks such as “Straight, No Chaser,” “Crepuscule with Nellie” and “Epistrophy.”

You could savor Marsalis’ work in live performance, as well, especially at Snug Harbor, on Frenchmen Street in New Orleans. For decades, Marsalis played the landmark club once a week, and tickets were hard to come by. He last performed there in December.

Marsalis appeared often in Chicago, offering crisp, concise playing at the Chicago Jazz Festival in 1995; shimmering pianism at the Chicago Cultural Center in May of that year; and unmistakable integrity and reverence for jazz fundamentals during a concert at the College of Du Page Arts Center in Glen Ellyn in 1991.

“Consider his characteristically suave version of the old standard ‘Someday My Prince Will Come,’” I wrote in my review of that performance. “In just the opening bars, Marsalis spelled out the hallmarks of his pianism: warm tone, articulate touch, gently swinging rhythm, an unusually sophisticated sense of harmony and an elegant way of shaping a melody. Through the course of the evening, these elements remained constant, even if the historical reference points were in flux.”

Marsalis’ frequent visits to the Chicago area reflected his affinity for this city and its deeply held jazz traditions.

“In 1953, Jesse Bell, my friend and schoolmate at Dillard University in New Orleans, decided to go to Chicago,” Marsalis wrote in the foreword to my book “Let Freedom Swing: Collected Writings on Jazz, Blues, and Gospel.”

“It was August and, just before starting our junior year, we thought it would be a good idea to take the City of New Orleans train to Chicago. We had many classmates from Chicago and Detroit, and we timed it so we would all come back to school together. This was the year that Chicago became one of my favorite cities for all time.

“I was eighteen and looked and acted sixteen, which caused me to get tossed from the Crown Propeller nightclub with a poorly doctored draft card. However, we were more successful getting to hear Nat ‘King’ Cole downtown.”

Marsalis’ love for life and music in Chicago never waned, a bond nurtured by Wynton Marsalis, whose uncounted performances here with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra always are sold out. Like his father, Wynton Marsalis has built his career on the ethos of upholding jazz standards and yielding no ground to the commercial interests of the pop music industry.

As he put it to me in 1991, “I’m not for the use of the name of jazz to co-sign anything that doesn’t truly represent jazz.”

Wynton Marsalis has been criticized for this stance by those more willing to make artistic concessions, a fact that has had zero influence on his music, just as was the case with his father.

Nor is there any doubt as to where Wynton Marsalis acquired his reverence for what jazz musicians have fought, bled and died to create during the past century-plus.

“I suppose he picked up some of that from my classes,” Ellis Marsalis told me, referring to the many future artists the elder Marsalis taught at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, including Wynton and Branford Marsalis, singer-pianist Harry Connick Jr., and trumpeters Nicholas Payton and Terence Blanchard.

So Ellis Marsalis’ legacy endures not only through his recordings and through the memories of those lucky enough to have heard him in performance, but also through the work of his sons and other musicians who have tried to live up to his example.

“I only ever wanted to do better things to impress HIM,” wrote Wynton Marsalis on his blog the day after his father’s death (Dolores Marsalis died in 2017).

“He was my North Star, and the only opinion that really deep down mattered to me was his, because I grew up seeing how much he struggled and sacrificed to represent and teach vital human values that floated far above the stifling segregation and prejudice that defined his youth but, strangely enough, also imbued his art with an even more pungent and biting accuracy.”

“For me,” concluded Wynton Marsalis, “there is no sorrow only joy. He went on down the Good Kings Highway as was his way, a jazz man, ‘with grace and gratitude.’

“And I am grateful to have known him.”

So am I.(Chicago Tribune/TNS)