But the film about the removal and sale of a graffiti work on a concrete wall by anonymous British street artist Banksy in Bethlehem also serves to put a human face on an area beset by violence, said director Marco Proserpio.

"Most of the things I have seen about Palestine was picturing them as victims – not just victims but not human beings," the 33-year-old Italian filmmaker told Reuters.

"It's not the common story you tell about Palestine," he added. "The Banksy artwork was the right occasion to picture them as human beings."

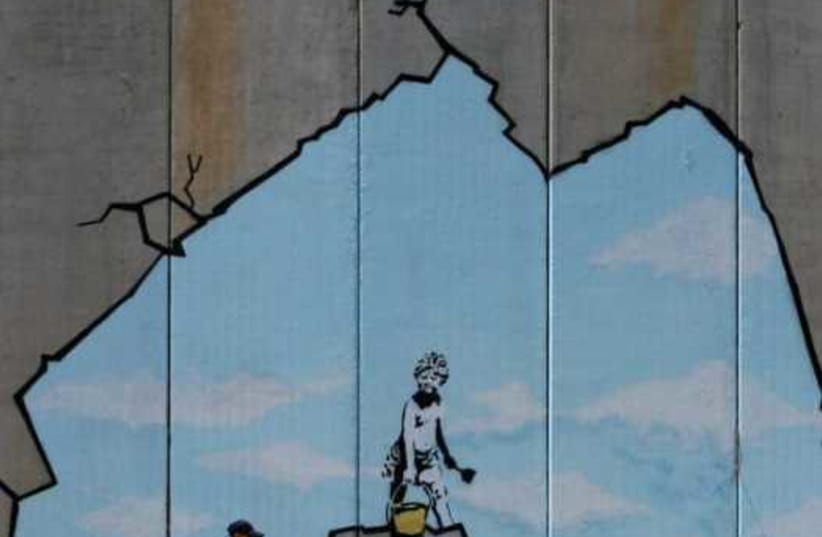

Banksy, who works in secret and whose artwork has fetched six-figure sums at auction, traveled to Bethlehem in the West Bank in 2007 and painted six images in the birthplace of Jesus.

The film focuses on one work - a black spray-painted donkey whose documents are checked by an Israeli soldier in an ironic twist on the Jewish state's strict security - and how one day it went missing from its concrete wall.

A main player Proserpio encounters is taxi driver and amateur bodybuilder Walid the Beast, who with the help of a well-off local businessman has the work removed and listed on eBay for $100,000.

A Danish collector buys the work but has so far been unable to resell it, and it now sits in European storage as a commodity, removed from its original context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

"I wanted to investigate the different consequences of this action," Proserpio said.

The film, narrated by punk rocker Iggy Pop, dives into questions of ownership, theft and the sale of street art, whose creators may never see a penny when their public displays are taken into private hands.

While Banksy's works are public sensations in Europe and the United States, the film shows ambivalence among many in Bethlehem.

Older residents are insulted by the implication they are donkeys, which is like calling someone an idiot in Palestinian society.

At one point, Walid declares, "Banksy can't change anything."

But the documentary shows the effect on younger Palestinians, who understand the attention and power street art can give to individual expression amid the ongoing conflict.

It is, in fact, a universal story, Proserpio believes.

"It's a primal need to write on walls to communicate with the people around you," he said.