Two thousand years ago, deep in ancient upper Egypt, some 200 km. from the great city of Luxor, students were being made to repeat their writing lessons over and over and over again on pieces of broken pottery until their letters were written correctly. Apparently, this is much like students have been made to do the whole world over for centuries.

Evidence of these written “punishments” was discovered among a cache of 18,000 inscribed pottery sherds uncovered by a team of German and Egyptian archaeologists in recent excavations of the ancient city of Athribis, located about seven km. southwest of the city of Sohag on the west bank of the Nile River.

Also among the sherds, known as ostraca, were remains of vessels and jars used as writing materials documenting lists of names, purchases of food and other everyday objects, providing a variety of insights into the daily life of the residents of Athribis.

The ostraca were recovered during excavations led by Prof. Christian Leitz of the Institute for Ancient Near Eastern Studies at the University of Tübingen in Germany, in cooperation with Mohamed Abdelbadia and his team from the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, who have excavated there since 2003-2019.

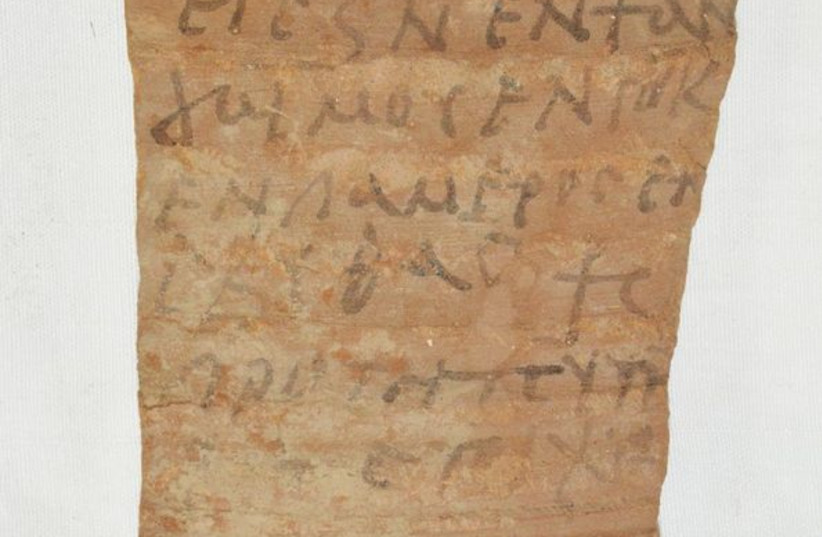

In ancient times, these ostraca were used in large quantities as writing material, using ink and a reed, or a hollow stick called a calamus, to inscribe the pottery.

“Papyrus was expensive, so people used the ostraca for daily use,” Leitz said. “They would write on the broken pottery for bills, or receipts if they gave someone three buckets of oil, or a sack of lentils. Or it could be used for writing material in school. You can copy on it and take notes, and save it for some time and keep it like we do today. Then when they didn’t need it anymore, they threw it away.”

The archaeological zone of Athribis, which is almost entirely unexcavated, extends over 30 hectares (74 acres) and consists of the temple district, the settlement, the necropolis and the quarries.

A 15-year project funded by the German Research Foundation began in 2005 to excavate and publish research about a large temple in Athribis built by Ptolemy XII, the father of the famous Cleopatra VII. With the completion of the project, the temple is now open to visitors.

The sanctuary was built about 2,000 years ago for the lion goddess Repit and her consort Min and was converted into a nunnery after pagan cults were banned in 380 CE.

SINCE SPRING 2018, excavations have been underway west of the temple at another sanctuary, and the team came across the numerous ostraca in the rubble. The excavations are ongoing.

It is very rare to find such a large quantity of ostraca, and this is only the second such large hoard ever found in Egypt. The first was a store of medical ostraca found in the workers’ settlement of Deir el-Medineh, near the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, in French excavations between 1922 and 1951.

“The number of the finds will allow us to know much about daily life in the ancient city of Athribis, but analyzing and translating all these texts will take years,” Leitz said.

Around 80% of the sherds are inscribed in Demotic, the common administrative script in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, which developed after 600 BC from Hieratic, the ancient Egyptian cursive writing used from the first dynasty until about 200 BC. Among the second-most common finds are ostraca with Greek script.

The team also found inscriptions in hieroglyphics and, in a smaller quantity, inscriptions in Coptic, which is associated with the early Christian church in Egypt and Arabic script – all attesting to the multicultural character of the city.

“Egypt at that time was for a good part bilingual,” Leitz said. “The native people were speaking Egyptian and writing in Demotic, but if you [wanted] to make a career, knowledge of Greek was necessary.”

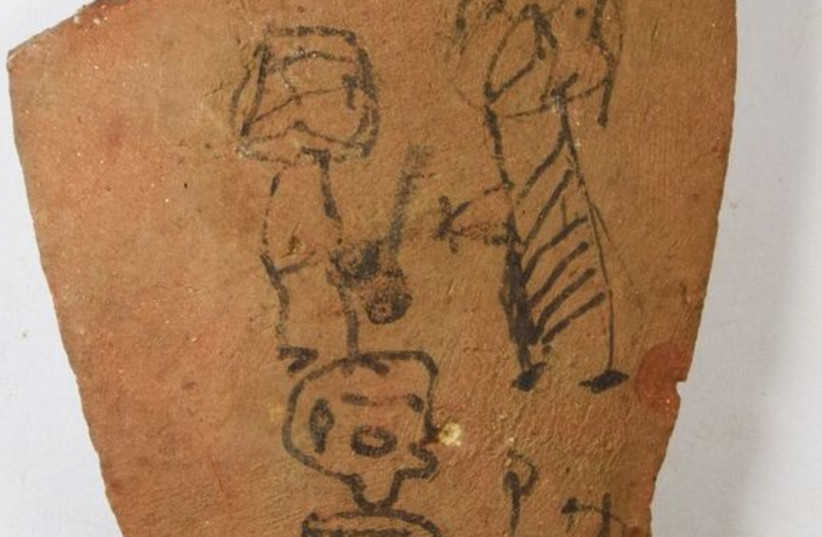

The archaeologists also discovered pictorial ostraca that show various figurative representations, including animals such as scorpions and swallows, humans, gods from the nearby temple and geometric figures, he said.

One ostracon that was found with the motif of a baboon and an ibis, and sacred animals of Toth, the ancient Egyptian god of wisdom, may have been associated with the school that is thought to have been located near the temple, Leitz said.

Hebrew University Egyptology Prof. Orly Goldwasser, who was not connected to the dig, said the finds were from the later Egyptian period, which is from when many finds have been excavated.

“The amount found is very big, and maybe when they go over all the material, they may find something interesting,” she said. “There may be administrative things for those who are interested in this period.

“Even if it is from the late period, to find such a huge amount of ostraca can be promising. At least we will have details of everyday life, which is always interesting. They may find other things, but they still need to do more studies.”

The contents of the ostraca are largely mundane lists of various names, different foods and other items of daily use. The team said it was surprised by an especially large number of the sherds, which seem to have come from an ancient school.

“There are lists of months, numbers, arithmetic problems, grammar exercises and a ‘bird alphabet’ – each letter was assigned a bird whose name began with that letter,” Leitz said.

Some of the hundreds of samples of ancient school work are inscribed with the same one or two characters, on both the back and front of the sherds, the researchers said, and that led them to believe these were sorts of “punishment” or practice exercises for students who did not know their letters correctly.

Leitz said the discovery of these texts that may prove the temple was part of the school was especially intriguing for him.

“Kids were sent to the temple to make copies of hieroglyphic texts,” he said.