A new link may have been found between the early modern humans of Britain and those of mainland Europe that can answer questions about early human evolution, who the direct ancestor of the Homo Sapien is, and why no other species of early human survived, according to a new study conducted by the UK Natural History Museum.

Published in the Journal of Human Evolution, the study examines the connection between the oldest known human remains in the UK and a collection of early human fossils found in Spain known as the Sima de Los Huesos (pit of bones) hominins.

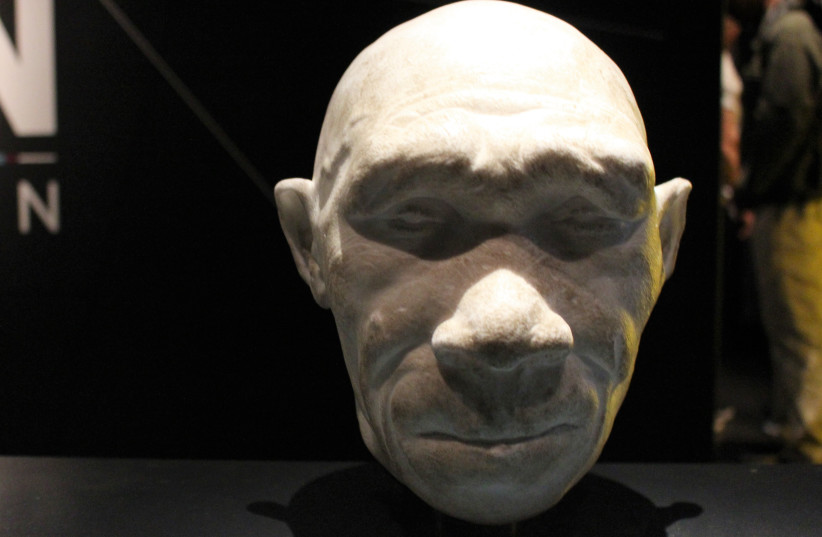

The earliest human remains in the UK date back to around 480,000 years ago and are located in Boxgrove, West Sussex. Consisting of part of the lower leg bone and two incisor teeth, the fossils were, until recently, considered part of the Homo Heidelbergensis, who most likely existed at the same time as both the Homo Neanderthalensis and the Homo Sapien.

However, since 1997, more than 5,500 human skeletal remains have been uncovered in the Atapuerca archeological site in Spain. This collection of early human remains has become known as the Sima de Los Huesos, and although they were at one point also classified as belonging to the Homo Heidelbergensis, they are now commonly believed to be early Homo Neanderthalensis - or Neanderthals.

Comparing the three fragmented fossils in Boxgrove to the extensive collection in Atapuerca, scientists and researchers from the Natural History Museum set out to try and understand if they had perhaps misclassified the Boxgrove fossils as H.Heidelbergensis, and thus missed the connection between evolution on mainland Europe and on the British Isles.

Examining the teeth and tibia of the Boxgrove fossil

The role that teeth play in understanding evolution is a crucial one, as the two tissues that they are composed of - enamel and dentine - survive long after all other natural tissue has decayed into nothing. This means that they are able to depict their genetically inherited patterns and their evolutionary history with much more accuracy than any other organ.

Comparing the two incisors from the Boxgrove fossil to those found in the Sima de Los Husesos, the researchers found extensive similarities between the two, including the length of the incisor root and a narrower root diameter.

These findings, the research states, reveal "that Boxgrove and Sima de Los Huesos are different from late Neanderthals, which share with other Early and Middle Pleistocene groups a more robust conformation."

Unlike the teeth, however, an in-depth comparison of the partial lower leg bone contradicts the theory that the two hominin groups of Spain and Britain were one and the same.

While the Boxgrove tibia fragment was determined to have thicker bone walls than the modern human - in line with the Sima de Los Huesos and Neanderthals - the midsection of the bone (known as the tibial shaft) was straighter than that of a Neanderthal's and more similar to that of a modern Homo Sapien.

Is the Boxgrove human connected to the Sima de Los Huesos after all?

According to the study's findings, it is unlikely that the Boxgrove remains are as closely linked to the Sima de Los Huesos or Neanderthals as had been theorized.

"Although the enhanced robusticity of the Boxgrove tibia could reflect a greater body mass and elevated activity levels, shape and surface feature contrasts between Boxgrove and Sima de los Huesos suggest a level of population difference, whether recognized specifically or not," write the study's authors.

However, this doesn't mean that they are content with the current classification of the Boxgrove human either and are still unsure as to whether or not it actually does belong in the Homo Heidelbergensis category.

"When the Boxgrove finds were made and described in the 1990s, there was much less material known and published from the Middle Pleistocene of Europe, and the provisional assignment of the Boxgrove fossils to H. Heidelbergensis was made more on chronological than morphological grounds," they write in the conclusion of the study.

"We are fortunately in a much better position now in terms of fossil material," they continue, "but the intervening years have also led to a growing realization of the complexity of human evolution in the Middle Pleistocene era with the apparent co-existence of different human lineages/species."

The trouble with understanding evolution

Regarding the difficulty with categorizing early human fossils, Natural History Museum evolution expert and co-author of the study Professor Chris Stringer explains the changes that evolutionary sciences have gone through in recent years, using the new research as an example.

"The whole Heidelbergensis story has become much more complicated,' says Stringer. "Since the Boxgrove discovery, many more fossils have been attributed to Heidelbergensis and they show a lot of variation. When the fossils at Sima de Los Huesos started to be found in the 1990s, they were also called Homo Heidelbergensis.

"If a fossil didn't appear to belong to Homo Erectus, Homo Sapiens or Neanderthals, it was often placed into the category of Homo Heidelbergensis. But more work has since been done on the Sima sample, which showed it was much more likely to be early Neanderthal based on physical features and DNA analysis."

Despite the difficulties, the researchers are hopeful that the insight gained on the Boxgrove fossil, and the similarities and differences of its various fragments will help to further the understanding of human evolution.

Study co-author Dr. Matthew Pope addressed these hopes with the Natural History Museum, saying that "this research brings us a step closer to understanding how the Boxgrove people were related to other European populations in the Pleistocene."

"The picture is complex, given the teeth appear close to those from Sima [de Los Huesos] and the tibia a little more distant. But we must remember that they were found in different sediments at the Boxgrove site. Establishing how separated in time these sediments are from each other is now an important research question for science to address."