Archaeologists from the University of Haifa and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have found silver coins made in Anatolia (Turkey) in the 17th century BCE, the Middle Bronze Age, at archaeological digs from the beginning of the Late Bronze Age, a century later.

The coins, which were used in regional trade, including with ancient Israel, were discovered at Tel Shiloh near Jerusalem, Tel Gezer on the western slopes of the Judean Hills and Tell al-Ajjul in the Gaza Strip.

Their discovery proves the use of silver coins as money in the southern Levant and precedes by 500 years what was thought to be the use of such coins.

The identification of Anatolia as the source of the money indicates continuous and long-term trade with Asia Minor.

“Moving to an economic method based on silver coins, which do not spoil and have a small volume and weight compared to grain brings with it many advantages and new possibilities that will surely contribute to the urban and economic development of the entire area.”

Dr. Tzilla Eshel

“Moving to an economic method based on silver coins, which do not spoil and have a small volume and weight compared to grain, brings with it many advantages and new possibilities that will surely contribute to the urban and economic development of the entire area,” said Dr. Tzilla Eshel of the University of Haifa, who led the study.

It also showed that the silver coins continued to arrive frequently and are evidence of long and stable trade relations with Anatolia that were unknown to researchers until now.

The history of coins being used as money

The use of coins as a means of payment was known in Mesopotamia as early as the third millennium BCE. However, in the southern Levant region, known in the Bible as the Land of Canaan, it was thought that such use was common only in the Iron Age, starting from the 12th century BCE.

Silver trading between Hazor and Mari, an ancient Semitic city-state in what is today Syria, is mentioned in financial documents found in Hazor from the Middle Bronze Age.

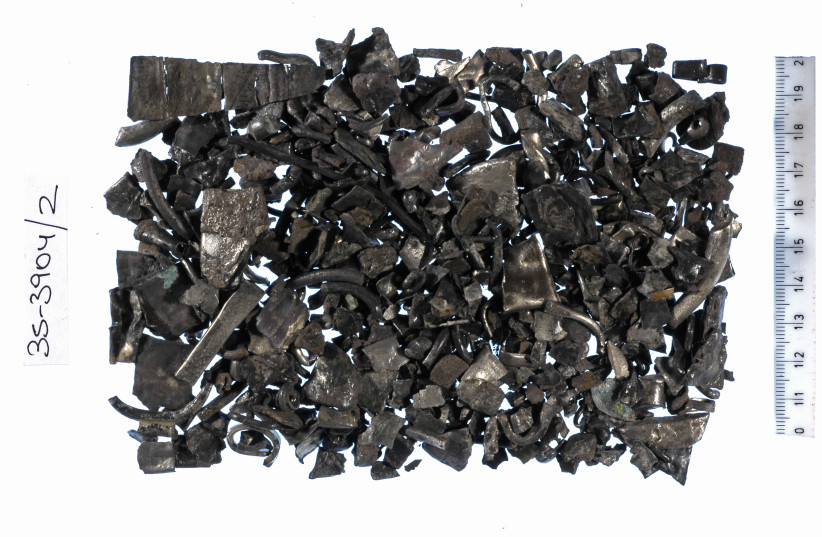

The silver coins are pieces of silver whose unpolished form clearly indicates that they are not jewelry or ornamental objects. That they were usually found together, wrapped in cloth and kept in pottery, indicates that they were used as a means of payment.

Previous studies by the team of researchers – Eshel, Prof. Yigal Erel and Prof. Naama Yahlom-Mack from Hebrew University and Prof. Ayelet Gilboa from the University of Haifa – dealt extensively with silver hoards from the Iron Age and located their origin.

However, the research on the silver traces revealed in previous excavations, some from recent years and some even decades ago, found that the silver hoards were from earlier periods, the end of the Middle Bronze Age and the beginning of the Late Bronze Age.

Until now, there was no comprehensive research on the subject. The concept that the use of silver coins in the southern Levant began in the Iron Age continued to dominate.

In the current study, the researchers examined silver hoards from Tel Shiloh and Tel Gezer.

“We had to establish that these were indeed silver coins used for payment,” the researchers wrote in their report. “Their shape, the fact that many of them looked like bracelets made in different sizes – that is, not for ornamental use – and the fact that they were found in public areas, inside a warehouse or near the city gate, led us to assume that they were indeed silver coins used for trade.”

The second step was to see if it was a large enough amount to assume that it was a comprehensive phenomenon and not a random case. According to the researchers, the amount of money found in the hoards in Shiloh and Gezer was not small. In addition, in old excavation reports of Tel Gezer, another significant number of silver hoards from the Middle and Late Bronze Ages were published, which indicated a large distribution of silver traces in the settlement.

“The researchers’ perception was that the use of money as a means of payment was a phenomenon that characterizes the Iron Age, but as soon as we examined it in depth, we saw that the use of silver coins had already existed since the Middle Bronze Age,” they wrote. “The number of silver coins in the hoards at Tel el-Ajjul can illustrate this very well: In these hoards, there were gold ornaments that attracted most of the attention of the researchers, but when we examined their composition, it turned out that there were many more pieces of silver and that gold objects were the minority.”

After reaching the conclusion that the quantities of silver coins indicated their widespread use as a means of payment, the researchers next looked to find out where they originated.

To identify the source of silver, an isotopic test was performed and compared with the isotopic composition of ores of known origin, as well as to other silver objects. In the examination carried out by the researchers, a similarity was found to ores originating in Anatolia, as well as to ancient silver objects found in excavations in Anatolia.

In addition, other things found in the vicinity of the hoard, such as an axe head or a pendant that apparently originated from Anatolia, led the researchers to the conclusion that the most likely source of the money was from there.

“We know for sure that in the Iron Age, this trade existed, but our findings move the beginning of such trade in metals back at least 500 years,” they concluded. “The significance is that we discovered the first evidence that there was a continuous and long-term trade of metals from the Levant region to Anatolia already in the 17th century BCE.”