In Germany, scientists believe the earliest human footprints in mankind have been uncovered. Found in the roughly 300,000-year-old Schöningen Paleolithic site in the Lower Saxony region, the prints have helped scientists learn more about the history of the world's ecosystem hundreds of thousands of years ago.

In this peer-reviewed study, scientists learned that footprints are believed to belong to Homo heidelbergensis, which was the first human species to live in cold weather and the first species to build shelters, creating simple dwellings out of wood and rock, according to the Smithsonian Institute.

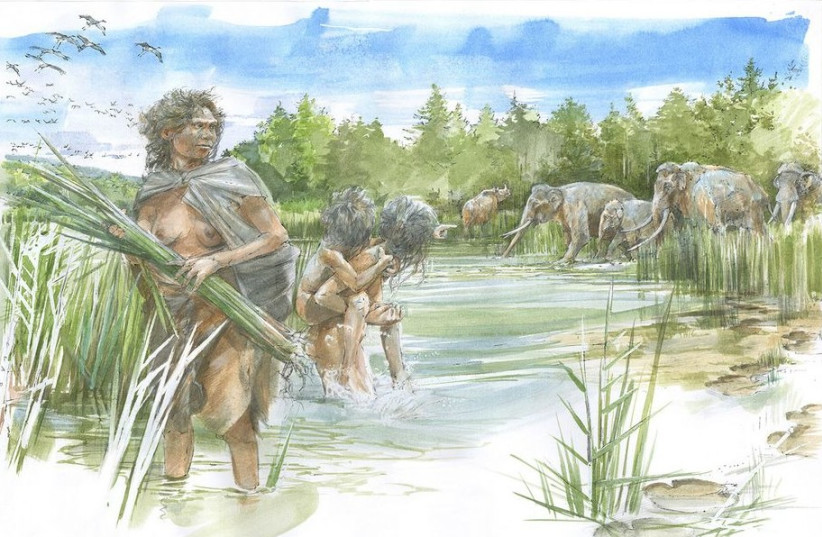

Scientists believed that a small family of "Heidelberg people" lived in what later became the Lower Saxony region. The group lived amongst wildlife like elephants, rhinoceroses, and other wildlife that would not be associated with the area today.

Scientists believe these footprints helped depict the ecological makeup of the area at the time.

In the newly published stud, Dr. Flavio Altamura, who is currently a fellow at the participating university's Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment, made crucial observations. “This is what it might have looked like at Schöningen in Lower Saxony 300,000 years ago,” Altamura explained.

“These tracks, together with information from sedimentological, archaeological, paleontological, and paleobotanical analyses, provide us with insights into the paleoenvironment and the mammals that once lived in this area. Among the prints are three tracks that match hominin footprints – with an age of about 300,000 years, they are the oldest human tracks known from Germany and were most likely left by Homo heidelbergensis.”

Not all traced tracks were human

According to the investigation, scientists connected two of the three traced tracks to individuals who were young and used the previously-existent lake for edible plants and fruits. Scientists believed the tracks found also shed light on the daily lives of early hominin groups, as well as their coexistence with large elephant herds and other small mammals.

“Based on the tracks, including those of children and juveniles, this was probably a family outing rather than a group of adult hunters,” Altamura said.

The human tracks were not the only ones recovered, according to participating archaeologists. Some belonged to the extinct species Palaeoloxodon antiquus, an ancient relative of the elephant. Dr. Jordi Serangeli, the excavation supervisor at Schöningen, stated that “There is also one track from a rhinoceros – Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis or Stephanorhinus hemitoechus – which is the first footprint of either of these Pleistocene species ever found in Europe.”