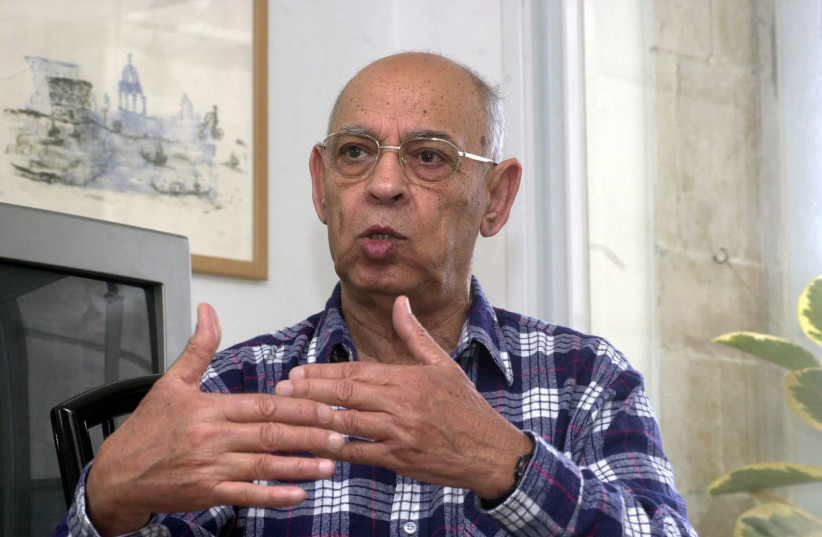

Sami Michael, the writer and civil rights activist whose novels explored prejudices and inequalities between Israeli Jews of different backgrounds as well as between Jews and Arabs, died on Monday aged 97.

Michael’s books have been translated into many languages and have won dozens of literary awards in Israel and around the world, including the Prime Minister’s Prize for Hebrew Literary Works in 1981 and the Agnon Prize in 2018. In 2002, Michael was awarded a Key to the City of Haifa, and throughout his career, the writer was awarded honorary doctorates from four major Israeli universities.

He was celebrated not only for his literary works but also for his social activism and work on behalf of human rights and coexistence in Israel. An avowed atheist, Michael was a fierce critic of religious extremism in Israel, as well as prejudices he saw among the state’s original Ashkenazi establishment against Jews from the Middle East and North Africa as well as against Arabs. He was also a candidate for the Knesset in 1992 and 1996, on the Meretz list.

Born in Iraq, Michael immigrated to Israel in 1949

Michael was born Kamal Salah in Baghdad in 1926. At 15, during his high school studies and following the rise of the pro-Nazi regime in Iraq and the 1941 pogrom in Baghdad known as the Farhud, Michael joined the Iraqi Communist Party.

In 1948, still bearing his birth name, a warrant was issued for his arrest. His father arranged for a smuggler to sneak Michael across the border with Iran, where he was forced to change his name.

In 1949, partly out of fear that the government in Iran would hand him over to the Iraqi authorities, Michael turned to the Jewish Agency and immigrated to Israel, despite an offer by the Communist Party to resettle him in the Soviet Union.

Michael first settled in Jaffa, then moved to Haifa, following an offer to join the editorial board of al-Ittihad, the only nongovernmental Arab newspaper published under the Israeli Military Governorate (1948-1966.)

The move was initiated by the author Emil Habibi after Michael sent two articles to the newspaper that prompted reactions upon publication. In Haifa, Michael lived in the mixed neighborhood of Wadi Nisnas, which later became the subject of his 1987 novel Trumpet in the Wadi. There, Michael wrote articles and stories for al-Ittihad and al-Jadid, with a regular column under the pen name Samir Mard.

"All Men are Equal - But Some are More"

In 1974, Michael published his first novel, All Men are Equal – But Some Are More (in Hebrew: Shavim v’Shavim Yoter), about the lives of immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa in transit camps in Israel in the 1950s. The title became a well-known phrase in Israel to speak of social inequality between Jews of different lineages as well as between Jews and Arabs.

In 1975, Michael published his first children’s book, A Storm Between the Palms, about the adventures and heroism of Jewish boys and girls in Iraq during World War II. In 1977, Michael published his second novel, Hasut, which revolves around a group of Jewish and Arab left-wing workers during the Yom Kippur War.

In the years 1981-1987, he translated the Cairo Trilogy, a series of three historical novels, which were written between 1957 and 1956 in Egypt by the Egyptian writer and intellectual Nagib Mahfouz.

In 1987, Michael published Hatsotsra Ba’wadi, which was adapted into a successful play a year later by Shmuel al-Safari. In 2001, the book was adapted into a film that won the best feature film award at the Haifa International Film Festival.

In 2001 he was elected to serve as the president of the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, a position he held until 2023.

Eulogized as "Israel at its best"

Michael’s death prompted words of praise from across Israeli society, and in particular from leaders of the political Left.

President Isaac Herzog eulogized the writer as “a giant among giants” who “made our bookshelf rich and spectacular.”

Zehava Galon, the leader of Meretz, wrote that Michael “was a political activist and a wonderful writer who knew how to see what Israelis insisted on missing, but above all, he was someone overflowing with humanity.”

Yair Lapid, leader of the opposition, spoke of Michael as “a warrior for peace,” and Merav Michaeli, of the Labor Party, eulogized the late writer as “Israel at its best.”