Taking her seat on the last plane out of Beirut to Israel, Sarah Shammah let out a sigh of relief. The year was 1947, just days after the United Nations had declared the partition of the Land of Israel and she had barely escaped from Aleppo where riots broke out against the Jews of the city and the Great Synagogue had been torched.

In her possession were 50 precious photographs and their negatives of the ancient synagogue, for which she had risked her life. But the risk had been worth it.

In a real-life drama that could compete with any episode from the modern TV shows of Fauda or Tehran, Shammah, a young Syrian Jew who had immigrated in 1932 to what was then Mandatory Palestine under British rule, had returned in the autumn of 1947 to Aleppo, the city of her birth, to work on a project commemorating her father’s life and work by recording the Great Synagogue of Aleppo in a memorial photographic album. A premonition of approaching danger had propelled the young mother to make the return trip to Syria even as tensions rose in the region, leaving her son in Jerusalem.

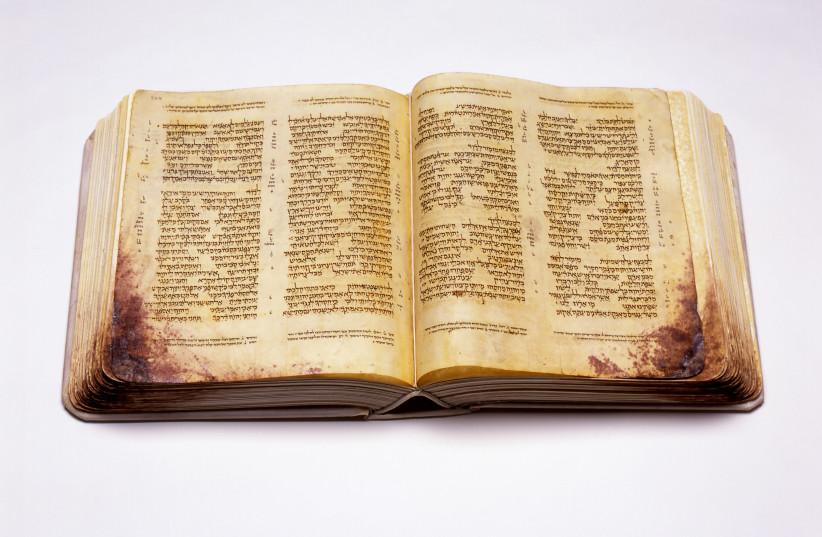

In Aleppo, once the center of a thriving Jewish community, she had hired a local Armenian photographer to meticulously photograph the Grand Synagogue building, the treasure of the Aleppo Jewish community where the sacred Aleppo Codex—considered to be the most accurate existing manuscript of the Masoretic text which was written at the beginning of the 10th century CE and is listed on the UNESCO’s World Heritage list—was kept carefully protected in what was known as “Elijah’s Cave.” They photographed every corner of the building, including the adjacent cemetery and garden.

As fate would have it, as they completed their work the UN made the partition declaration, the riots broke out in Aleppo and the synagogue was burned and with that the Aleppo Codex disappeared. The Armenian photographer realized the value of the negatives he had taken as the last images of the ancient synagogue, and demanded Shammah return them and the photographs to him, threatening to turn her in as a Zionist spy. That is when she, together with her brother, made their escape to the Lebanon border with the help of a Syrian Muslim friend.

Seventy-five years later, those images served as the base for an innovative exhibition of the synagogue which just opened at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Using the advanced technology of virtual reality to produce a digital 3D model of the synagogue, the exhibit brings back to life a community and a period long since vanished.

“In 1947, knowing that the borders might close, and that a war could break out, Sarah Shammah used the best technology of her time, which was photography, to do what no one else had done taking 360 degree photographs of the synagogue,” said Avi Dabach, who together with Judith Manassen Ramon, Mike Robbins and Harmke Heezen created the VR experience. “Now we are using the best technology of our time to present her work.”

While working on a documentary film on the mystery of the lost Aleppo Codex, Dabach and Manassen Roman came across Shammah’s story, and were given access to the photographs by her son Avraham Hever.

Dabach’s great-grandfather, Ezra Dabach, was the caretaker of the Aleppo synagogue and he had grown up hearing stories of the wondrous synagogue from his grandfather. He and Manassen Roman decided to move forward with a VR project suggested by their German partners.

Through discussions with the museum on how to present the one-thousand-year history of a synagogue, they decided to base the VR experience, five years in the making, solely by remaining faithful to the photographic images, thus the VR represents the synagogue as it looked at one specific time, on one specific day, he said.

“When we saw (the initial version) the first time it was so impressive and we felt the difference. This is not a film. This is being present in a place, being present at a special time,” said Dabach.

The VR exhibit reconstructed the synagogue through photogrammetry, mapping, and archival photographic information dating back to the early 1900s. The VR experience, which enables visitors to enter the synagogue and explore its impressive interior, extends the museum’s Synagogue Route, featuring four reconstructed synagogues brought to Jerusalem from three continents. The Back to Aleppo exhibit offers two “tours” including Shammah’s story as well as a virtual tour of the synagogue.

“This is a different experience,” noted Revital Hovav, curator of the Back to Aleppo exhibit. “We are trying to connect to a younger audience and we can do this through high tech. We don’t do this for every synagogue, only for one that does not exist. It is a mixture of the old world and the future world.”

The Great Synagogue of Aleppo was built between the fifth and seventh centuries CE and in its last form included seven heikhalot, the Sephardic Jewish term for Torah arks. The synagogue was destroyed and rebuilt twice—first in 1400 by the Mongol armies that conquered Aleppo and then in the 1947 riots. It was destroyed once again in 2016 during the Syrian civil war and has since been abandoned and lain in ruins.

In a separate and fascinating turn of events, part of the ancient Aleppo Codex ultimately found its way, hidden inside a washing machine, to Israel and is now at the Israel Museum’s Shrine of the Book. Thought to have been made up of some 410 pages, only 294 pages of the codex have been recovered, noted Dr. Adolfo Roitman, Curator of the Dead Sea Scrolls and Head of the Shrine of the Book. Where the remaining pages are remains a mystery, though a burnt fragment of the codex which had been kept in the wallet of an Aleppo Jew living in Brooklyn as an amulet surfaced and was donated to the museum about 15 years ago.

Shammah’s photographs have allowed VR experience creators to recreate the rich heritage of the proud Aleppo community, the “big and great and beautiful” synagogue of Dabach’s grandfather’s memory, noted Manassen Roman.

“Only because of (Shammah’s) courage and decision to do something without fear do we have these pictures and we can do something with them,” said Manassen Roman. “We owe a lot to Sarah.”

The exhibition was made possible thanks to a dedicated gift from the Moise Y. Safra Foundation, New York to honor the history and contributions of the Aleppo community and the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation, New York.

Pre-registration for tickets for the VR exhibit, which runs through December 31, 2023, is required. https://www.imj.org.il/en/exhibitions/back-aleppo

Sydney Cohen contributed to this report.