Artificial intelligence-generated art cannot be protected by copyright, a US federal judge ruled on Friday, in a piece of legislation that may codify intellectual property rights regarding creative works made by AI as opposed to those made by humans.

The ruling was made by US District Court Judge Beryl A. Howell and backed up findings made by Shira Perlmutter, the register of copyrights and director of the US Copyright Office, ruling against the plaintiff, Stephen Thaler.

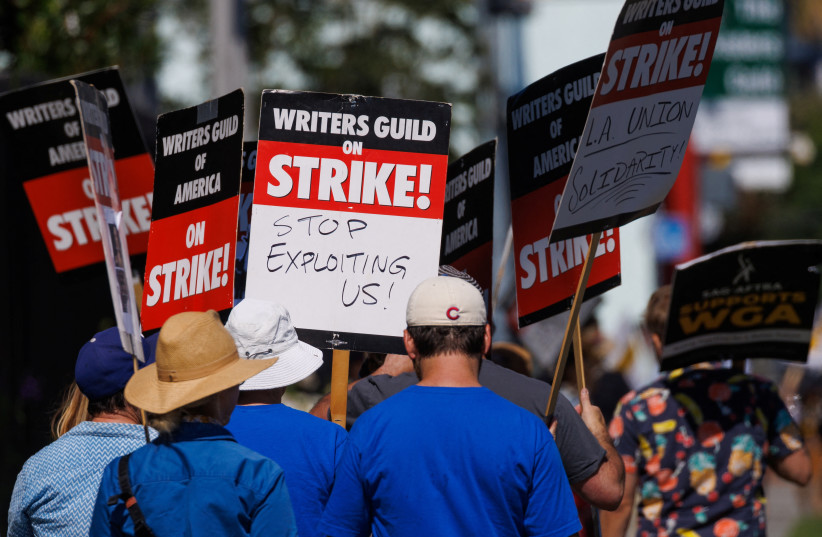

The significance of the ruling comes amid the ongoing writers' and actors' strikes in Hollywood, which centers on fears that Hollywood studios will use AI-generated work to avoid having to pay writers and eventually actors.

Sorry to AI generative art: No copyright shall be given to art not made by humans

The background to the ruling goes back to before the Hollywood strikes. Thaler, who heads the neural network firm Imagination Engines, has been trying to get AI recognized as being able to author creative works for years.

Note that despite being AI all the same, Thaler's "Creativity Machine" AIs, which he has been working on since the 1990s, far different than something like ChatGPT, with a greater emphasis on replicating human cognition rather than relying on thorough user input.

Thaler's achievements eventually resulted in the creation of a complex and powerful AI that he dubbed the Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience (DABUS).

According to an article in the Economist's 1843 Magazine, Thaler truly believes his AI is creative and that DABUS has feelings and experiences loneliness.

In 2018, Thaler attempted to list his Creativity Machine as the sole author of the artwork A Recent Entrance to Paradise, which his AI created and listed himself as the owner of the copyright as the artwork was considered a work-for-hire piece.

The US Copyright Office denied this application due to the artwork not having been made by a human, prompting Thaler to sue. He had argued that US copyright law is meant to be malleable so it can adapt to the times, specifically citing a number of court cases to that effect, including the case Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, which upheld that copyright includes photographs.

But Judge Howell sided with the Copyright Office.

What is especially significant about this ruling isn't just how it wouldn't give authorship to the AI, but that the AI's users, in this case, Thaler, wouldn't be granted ownership of a copyright under the work-for-hire doctrine.

The work-for-hire doctrine states that if someone were hired by someone to create something, the copyright for that creation would belong to the one who paid the author to make it, though authorship itself would still belong to the creator.

This itself is a now widespread exception to standard copyright law, which supposes that a creator owns the copyright to what they create.

This is no mere accepted tradition but is enshrined in the American legal system, such as in the US Copyright Act of 1976.

Interestingly, it also differs from traditional copyright in terms of length, with work-for-hire copyright being protected for 120 years after creation or 95 years after publication, depending on which comes first. By contrast, the typical copyright protection only lasts for the lifetime of the author plus 70 years.

If the Copyright Office had accepted that Thaler's AI authored an artwork and that Thaler, therefore, owned the copyright, it could mean that anyone who used an AI to make something could claim ownership of its copyright.

However, Perlmutter refused to grant this copyright protection, something Howell agreed with.

"United States copyright law protects only works of human creation," the judge wrote in her ruling.

The reason for this, and the reason why the court disagreed with Thaler's argument, is "a consistent understanding that human creativity is the sine qua non at the core of copyrightability, even as that human creativity is channeled through new tools or into new media."

Howell also cited some other precedents in this regard, including the cases Urantia Found v. Kristen Maaherra, where the court ruled that the book supposedly created by divine celestial beings and not humans needed to at least have some degree of human creativity and involvement to be copyrighted.

But what may be the most relevant case cited was Naruto v. Slater. This case referred to an incident when a crested macaque monkey named Naruto managed to get its hands on a camera and take pictures of itself. A lawsuit had been filed on the monkey's behalf by PETA after the pictures were included in a book.

At the time, the court ruled against Naruto because while Naruto objectively did take the picture, he was still a monkey and not a human, and thus ineligible to author any creative work.

An AI was denied authorship of creative work: What does this mean for Hollywood?

With generative AI becoming more prevalent around the world, the question of its copyrightability has become increasingly relevant.

Back in March, the US Copyright Office said that most works made by AI can't be copyrighted, but works where the AI assistant can sometimes be copyrighted depending on the degree of human involvement.

This is also due to the spotlight placed on the issue by the ongoing Hollywood writer's strike, which has since passed 100 days as unionized writers attempt to fight against what they claim are studio efforts to sideline them in favor of more affordable AI.

At the same time, entertainment and media companies have been drastically boosting their spending in generative AI to the point of becoming global leaders in the field, according to Forbes, citing a report from the search and insights firm Lucidworks.

According to Nina Schick, an author and generative AI adviser who was speaking at a SAG-AFTRA panel at CES back in January, by 2025, 90% of all content may be, at least in part, AI-generated.