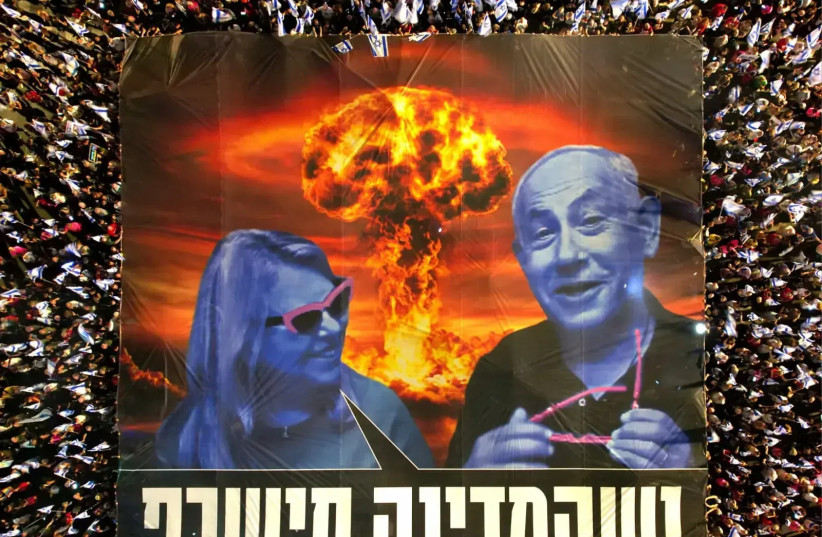

Even amid the chaos of Israel's war against Hamas in Gaza, one story stood out as particularly bizarre: Research by US law professors Robert Jackson Jr from New York University and Joshua Mitts of Columbia University, claimed that someone with advance knowledge of the October 7 massacre made billions — NIS 3.2 billion ($862 million), to be exact— by shorting shares of Bank Leumi.

It was a sensational tale by any measure.

The assumption was that Hamas or its affiliates, as the ones behind the attack, were the ones with exclusive knowledge.

The researchers based their claim on unusual short transactions they observed in the Israeli capital market, which they believed indicated the use of insider information about the possibility of a war and the subsequent drop in stock prices, particularly in Israel's financial sector. This revelation sent shockwaves through even those who are usually uninterested in economic news, leaving them to wonder: Can you profit from tragedy?

Some conspiracy theorists, lurking on the fringes of online discussion, saw this as evidence to bolster their claims. Here was a fact: Someone knew, someone prepared, someone profited — not only from the carnage, but also from a great stock market heist.

How do you short stocks?

To unravel this incredible story, let's delve into the mechanism of short-selling stocks in the capital market. Essentially, these transactions involve predicting a that a certain asset, such as a security, will decrease in valuable, becoming worth less money. In a short sale, the buyer pays the seller for the future right to purchase the asset on a specified day, allowing them to trade it at a higher value.

Confused? Let's break it down further: Imagine I believe that the value of a stock will sharply decline in a few days. I can "borrow" shares from someone who holds them for a small fee, with a promise to return them at their current value on a specific day, let's say a week from now. In the meantime, I sell the shares (which I don't actually own) at their high value, pocketing the proceeds, and then pay back the shares' owner on the agreed-upon day. If my hunch or the information I have is accurate, I only need to return, for example, NIS 80 for shares I sold at NIS 100.

The difference, in this case, would be my profit — NIS 20 (minus the commission). You might think this just sounds like a legal form of gambling — and you wouldn't be far off. Trading stocks and currencies often involve calculated risks based on information and analysis, but they also have an element of gambling. In fact, many respectable companies offer trading platforms that allow their members to bet on various assets, from oil prices to stock values, with just an account and a desire to turn hunches into money, all while paying a commission to the platform.

Some trades are based on data and in-depth analysis, while others rely solely on that hunch, much like a gambler betting on a roulette wheel landing on either black or red.

Now, let's connect the worlds of politics and finance. In the business realm, there are limitations on the use of "insider information." For example, a CEO who knows that their company is about to sign a contract that will significantly increase their capital is not allowed to buy shares (which would cause their value to skyrocket).

Conversely, a board member who realizes that the situation is deteriorating cannot sell their shares to avoid losses. These transactions are usually carried out through a third party to obscure the connection between the source of the information and those benefiting from the deal.

In the political world, the equivalent would be insider information from a cabinet member about a decision to initiate a war, which would likely cause a significant drop in stock prices on the local stock exchange.

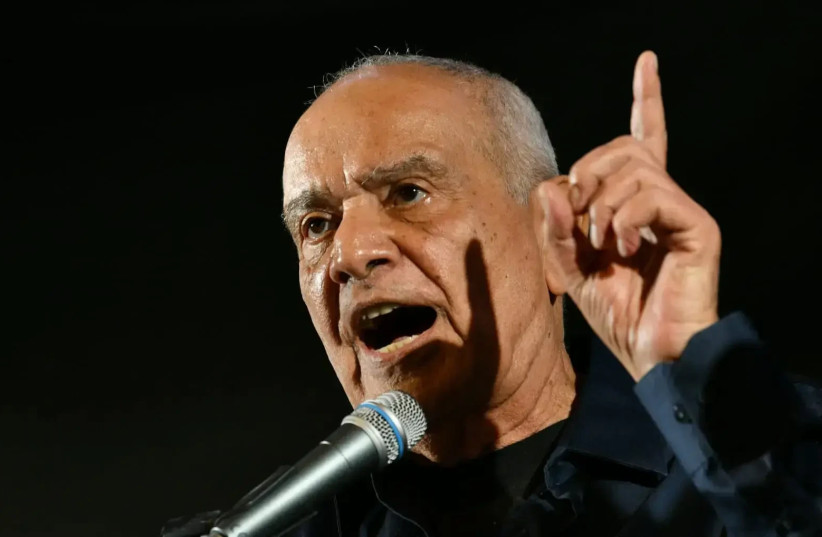

One well-known case in Israel is that of former IDF chief of staff Dan Halutz, who sold his stock portfolio a few hours before the outbreak of the Second Lebanon War (as reported by Maariv at the time). While the story created a stir, it was ultimately claimed to be a coincidence and involved a relatively small amount of money.

Halutz's total stock portfolio was valued at NIS 120,000 and at worst, the savings he made by selling them at that time were only about NIS 20,000 — a fraction of the total value. Thus, any allegation of insider trading remained nothing more than speculation.

Of course, there are also cases where prominent traders in the capital market suffer losses due to changes in the value of financial assets. In 2006, Eliezer Fishman lost a significant fortune after trading Canadian dollars for Turkish lira. Tempted by the higher return offered by the lira, Fishman sold his stable currency holdings, only to see the value plummet, leaving him impoverished. This demonstrates the close relationship between the political and security situation and the status of the market. Whether by hunches or solid information, someone can rake in billions.

Israel-Hamas war stock shorting conspiracy: What the research got wrong

Back to the strange mystery of Hamas and Bank Leumi shares: The US study claimed implicitly that someone with advance information about the Hamas massacre, executed an unusual short trade on Leumi shares (which indeed fell in value, like all Israeli shares, in the first days of the war).

How much did this dealmaker earn? According to the professors: NIS 3.2 billion! Not a bad amount for a day's work... but this isn't actually true. The reason why this is wrong, by the way, is nothing less than astounding: The study did not take into account that stock prices in Israel are denominated not in shekels, but agorot (NIS 1=100 agorot)... therefore, even if the claim is (allegedly) true, the profit must be divided by a hundred. In other words, rather than NIS 3.2 billion, this short only resulted in a profit of NIS 32 million ($8.6 million). Not a bad amount for a single operation, but already much less significant when it comes to corporations and large-scale stock trading.

What did we learn from the "Heist of the Century" that may not have even happened? Mainly things that are not related to finance, but to wartime psychology: Perhaps the desire to hurry, research, and publish something that corresponds with conspiracy theories; perhaps the unbearable ease with which academic papers are written that are supposed to be based, as is the way of science, solely on a collection of observations (that is, about reliable and accurate information); perhaps about our need for such stories, whether they are about get-rich-quick schemes, political-economic conspiracy, or even proof of the evil of Israel's enemy (as if we needed a story about a financial scheme to know that).

Those who still want to learn some lesson about the relationship between politics and the economy could find it in the position papers of the credit rating agencies, the ones that until October 7 engaged us in everything related to Israel's credit rating. There was not a single position paper that ignored the intensifying security threat within Israel's borders.

The section that hovered as a cautionary note above the rating agencies' assessments was almost identical for assessment bodies. It is true that it is not wise to estimate that a country like Israel is always under the threat of a regional flare-up, but here is another important lesson from these reports: We have examined them, at least since January 2023, in the context of a potential link between judicial reform and credit rating. We focused on these warnings and overlooked the security clause in these reports. In other words, because of our preoccupation with the judicial reform controversy, we did not see the real danger that lay before us.

Here we have an important lesson about economics and security. It's just a shame that this is wisdom after the fact.