They were young, intelligent and, thanks to their “Aryan” features, were able to slip sight unseen in and out of ghettos and Gestapo offices, while carrying out some of the most dangerous missions of the anti-Nazi Jewish resistance.

Bela Hazan Yaari, Tema Sznajderman and Lonka Korzybrodska – all members of the pioneering HeHalutz Zionist youth movement – smuggled people, documents, weapons, ammunition and money between ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe during WWII.

Though they were starved, weak, and sometimes tortured, the trio bravely risked their lives on numerous occasions to save others. But their story, and the stories of hundreds of other women who were in the Jewish resistance during the Holocaust, have long remained in the shadows.

Yoel Yaari, the son of Bela Hazan Yaari, is hoping to change that with an upcoming in-depth book that will tell the amazing untold stories of Hazan and her comrades. The story begins in 2017, when Yaari, a professor in neurodegenerative diseases at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, made a visit to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in Poland.

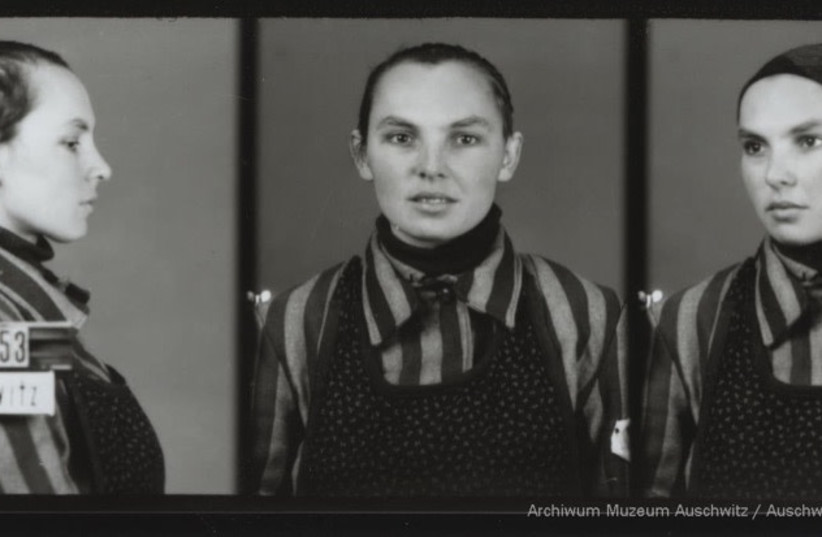

During his tour of one of the museum’s permanent exhibitions, he was surprised to find a mugshot of his mother displayed in an exhibit dedicated to Polish prisoners who had died in the camp. What’s more, the name beneath her photo was wrong.

“I had to solve this, [find out] how it happened – and then I started investigating,” Yaari told The Media Line. “I started discovering new things about my mother as well as about everything else that happened around her.”

“All my life I was really not so interested in that period,” he recounted. “My mother unfortunately didn’t talk much and we didn’t ask her, like many second-generation people who are reluctant to ask questions.”

Born in 1922 in Rozhyshche, Poland (now Ukraine), Bela Hazan escaped to Vilna in Lithuania when World War II broke out. After Nazi Germany occupied Vilna in 1941 and began murdering the city’s Jewish population, Hazan –who had Aryan-like features – assumed a Polish identity.

For the rest of the war and during her activities in the resistance, she was known as Bronislawa Limanowska. Her friends, Tema Sznajderman and Lonka Korzybrodska, also took on Polish names, becoming Wanda Majewska and Kristina Kosowska, respectively.

Together with other leading members of the underground, the three women played a critical role as couriers by smuggling critical information, weapons and more between the Jewish resistance movement’s chapters in Vilna, Lida, Grodno and Bialystok. Once news of the Nazis massacring Jews in the Vilna ghetto came to light, they also

helped to rescue some 50 Jews there.

“These three women organized an escape from the ghetto in Vilna to the ghetto in Bialystok, together with other people in the movement,” Yaari noted. “My mother was in charge of smuggling babies from Vilna to Bialystok.”

To further conceal her Jewish identity, the 18-year-old Hazan acquired a crucifix, Christian prayer book and visited church on a regular basis. She was assigned the task of finding a safe house in Grodno for couriers who were traveling from Vilna to Warsaw. “The couriers, who were mostly women, were traveling, passing information, smuggling people, arms and ammunition, as well documents,” Yaari explained.

The year was 1941. Thanks to her proficiency in a number of languages, Hazan began to work as an interpreter for the Gestapo in Grodno, a highly dangerous position that nevertheless afforded her the opportunity to steal official papers and documents that she then relayed to her comrades. The resistance used these precious items to create

forged documents, travel papers and IDs for their members.

One of the Gestapo members where the young woman worked became infatuated with her and invited her to the Gestapo headquarters’ Christmas party. Tema Sznajderman and Lonka Korzybrodska tagged along.

It was during that party that the Gestapo took the trio’s picture, an iconic black-and-white photo that now hangs on the wall of Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial, in a section dedicated to female couriers.

“Of these three women, only my mother survived; the other two women perished during the Holocaust,” Yaari said.

In June 1942, Hazan was sent to Warsaw to track her friend Lonka, who had disappeared while carrying out a mission for the resistance. During this trip, she was also asked to smuggle weapons and information. However, at the Malkinia border crossing on the way to Warsaw she was found out and arrested by the Gestapo, who suspected her of being a member of the Polish underground.

Hazan was tortured, interrogated and sent to a notorious nearby prison known as Pawiak, where she at last found her longtime friend Lonka.

It was not long before the two young women were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Yaari’s mother, who had some experience in medical settings, became a nurse in the women’s camp hospital. From there, she smuggled medicines to treat Jewish inmates.

“The hospital in Birkenau, as well as in the main camp Auschwitz, was also the center of the resistance groups,” Yaari related. “I don’t want to generalize, but my mother says that, in her barracks, the Polish nurses did not treat the Jewish women who were sick.” One of Hazan’s greatest acts of resistance came a short while later.

Both Hazan and Kozybrodska became ill with typhus, a common ailment in the camp, and were hospitalized in the same bunk. While Hazan managed to recover, her friend was not so lucky and her illness gradually worsened. She died on April 13, 1943. “Lonka died in my mother’s arms,” Yaari said. “Her last words that she told my mother were ‘you will survive and you will tell our story.’”

Others in the women’s camp, who were unaware of Lonka’s hidden Jewish identity, recited Christian prayers for her and placed an icon of Jesus on her corpse.

Risking her life once more, Hazan went to the chief SS doctor and begged him to be able to carry her friend’s body to the morgue herself so that it would not be disposed of in the usual unceremonious way. After the SS doctor reluctantly agreed to her request, Hazan carried Lonka’s corpse on a stretcher to the morgue and waited until she was alone.

“My mother couldn’t bear that her best friend was dying as a gentile, not as a Jew,” Yaari said. “My mother stayed with her, immediately removed the icon of Jesus and said Kaddish so that she could die as a Jew.” Kaddish is the Jewish mourners prayer. It may sound incredible, but this was not the end of Hazan’s heroic exploits during the

war.

In the spring of 1945, Hazan and 1,000 other women were sent from the Birkenau camp to the Taucha women’s forced labor camp near Leipzig, which was part of Buchenwald. As the Allied forces made their approach, the SS evacuated the camp and took all able inmates on a death march.

Hazan was left behind with Dr. Alexander Herman, a Jewish doctor from Prague, to tend to 140 sick inmates in the infirmary.

But the Nazis were not finished with Taucha yet. A mobile killing squad was headed straight for the remaining inmates in order to ensure that none of them made it to the Allied forces alive.

Hazan, Herman and other prisoners quickly put a plan into action, managed to rescue the 140 sick inmates and facilitate their escape into nearby American-held territory. Months after liberation, Hazan wrote about her experiences and provided one of the earliest testimonies of Jewish resistance against the Nazis, but it was not published until decades later in 1991 in Hebrew as a book titled “They Called Me Bronislawa.”

“She was so courageous; it’s just unbelievable,” Yaari said. “But she never spoke about it. These stories are unknown and, people like my mother, only now are these stories coming [to light].”

Hazan died in 2004 in Jerusalem, having never received recognition for her bravery. It was only in 2019 that she was posthumously awarded B’nai B’rith International’s Jewish Rescuer’s Citation, which honors Jews who rescued other Jews during the Holocaust.

Many other young women also were part of Jewish resistance groups during WWII.

Dalia Ofer, a professor emeritus of Holocaust and East European studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, is one of the leading scholars with expertise on women in the Holocaust, and has published several important books on the topic.

“When you talk about younger women, many of them were part of the resistance,” Ofer told The Media Line. They started as couriers to find and bring information. It was not easy to get information about what was going on from one ghetto to another. These women, because they were young and some of them were beautiful, could go out of the ghetto more easily, posing as Poles or Ukrainians.”

According to Ofer, in many ways it was simpler for women to get around during WWII because they were not as immediately identifiable as Jewish.

For his part, Yaari hopes that his book will be published by December this year, in time for what would have been his mother’s 100th birthday. Initially it will be in Hebrew, though he plans to have it translated into English as quickly as possible.

“It describes the portrait of my mother and also many other women,” he said. “There are many women whose function in the camps is absolutely not known in the standard historiography of Auschwitz. I’ve read almost 1,000 testimonies over the years and [examined] different stories to bring out a completely unknown story.”