Chaim Topol recalled that the first time he ever saw Fiddler on the Roof, “I nearly fled from the theatre with my hands to my ears.”

It wasn’t a two-bit off-Broadway version of Fiddler Topol had seen, either. He was in New York not long after the show opened and saw the original Tevye, Zero Mostel, in action. Though Topol remembered feeling that he was “in the presence of a genius” when he saw Mostel’s Tevye on a different occasion, that first show was an “off-day” for Mostel in Topol’s opinion. The veteran American actor had cracked inappropriate jokes off the cuff, turning Anatevka into “the shtetl Madison Avenue style,” according to Topol, who described it in his autobiography as:

“…reek[ing] both of the old golah (diaspora) as represented by the Russian Pale of Settlement, and the new one, as represented by New York: it seemed to reflect some of the worst features of both…”

His overall feeling regarding the show at the time? “Ugh!”

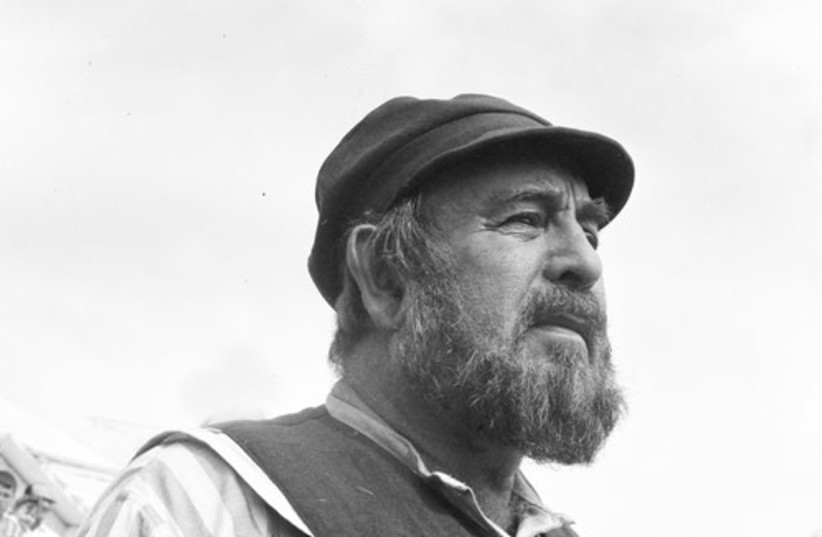

He also didn’t think it would work in Israel where, he assumed, the sensitivities and propensities were more in line with his. It wasn’t until seeing veteran Russian-born Israeli actor Shmuel Rodensky in the role of Tevye (known as “Tuvia” in Hebrew) that Topol was moved by the story and reconsidered a previous request he had rejected to take on the role in the Tel Aviv production of Fiddler.

Topol gets the role of Tevye

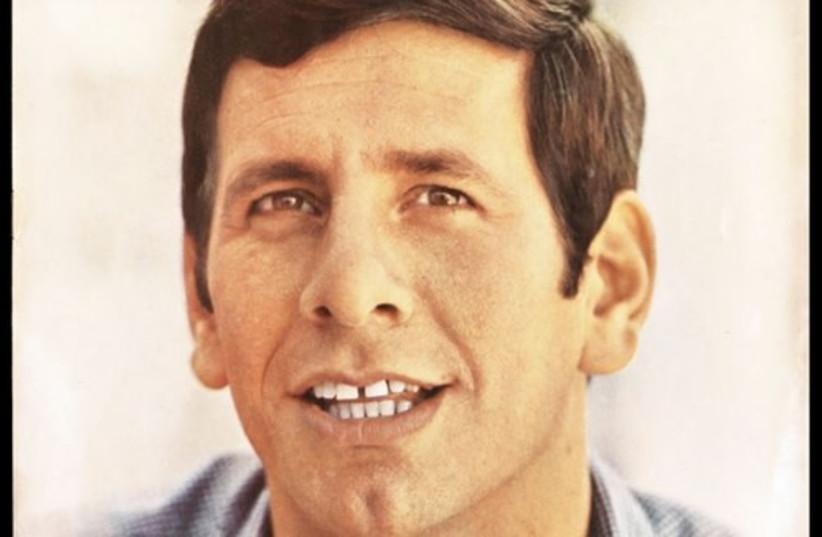

“I didn’t speak English and had a vocabulary of about fifty words – most of them swear words; but I managed to get by and I was told at the end of the day that the part was mine.”

Chaim Topol

Rodensky’s portrayal was more authentic and less comical, and when the older actor could no longer do all of the weekly shows, Topol – then in his late 20s – assumed the role.

Not long after, Topol was called to audition for the role of Tevye in the London production of the show. He had memorized the songs and much of the choreography for the audition, but his English was very poor.

“I didn’t speak English and had a vocabulary of about fifty words – most of them swear words; but I managed to get by and I was told at the end of the day that the part was mine,” he later recalled.

After months of practice and private English tutoring, Fiddler on the Roof, starring 31 year-old Chaim Topol as Tevye the Milkman, opened at Her Majesty’s Theatre in London on February 16, 1967.

Just about three months into the successful run, tensions began to build in the Middle East and war increasingly seemed imminent. Every night after his performance, Topol would rush to his dressing room to listen to the news.

His contract had specified that he would not work on Rosh Hashana or Yom Kippur, yet there was no “war clause”. After hearing the news that war had in fact finally erupted, Topol nonetheless told the show’s producer that he needed to take leave, and he “fled” to Israel.

Topol of course didn’t know that the war would only last six days. After reporting for duty in Tel Aviv and then finding himself in Jerusalem following its reunification and then in the Golan Heights, he promptly went back to being Tevye at Her Majesty’s Theatre, after only being absent for about a week. Following the war, Topol recalled how Israelis “suddenly began to think of themselves and speak of themselves as Jews,” while Jews abroad took pride in the war’s miraculous results.

“Jews who had seen Fiddler once came back to see it a second and third time, and some of the performances in June and July 1967 took on the character of a victory celebration,” he recounted.

A few years later, when preparations were being made to create a film version of Fiddler on the Roof, Chaim Topol was cast as Tevye, beating out legendary stars including Walter Matthau, Danny Kaye, Richard Burton and even Frank Sinatra.

According to the film’s director, Norman Jewison, Topol possessed “that don’t-mess-with-me pride that the Tevye of my imagination had”.

“Chaim Topol was made for this part. Not only is he a fine actor, but there was a strain of dignity. It was the Israeli in him, the pride of being Jewish that really struck me. When he said, ‘Get off my land,’ you could see him stiffen up and stand as tall as he could. There was a strength that epitomized the hope that these people would somehow create a country of their own.”

This article originally appeared on The Librarians, the official online publication of the National Library of Israel dedicated to Jewish, Israeli, and Middle Eastern history, heritage and culture.