Approximately 1.5 million children were murdered in the Holocaust; thousands who survived disappeared into convents, monasteries and Christian and Catholic foster homes.

“Hidden children” were given up out of love by desperate Jewish parents who wanted their children to survive what they foresaw to be unsurvivable. The children had to change their names, their histories and their religion to blend in, leaving them feeling lost and confused, struggling to make sense out of the fragmented pieces of their lives for years to come.

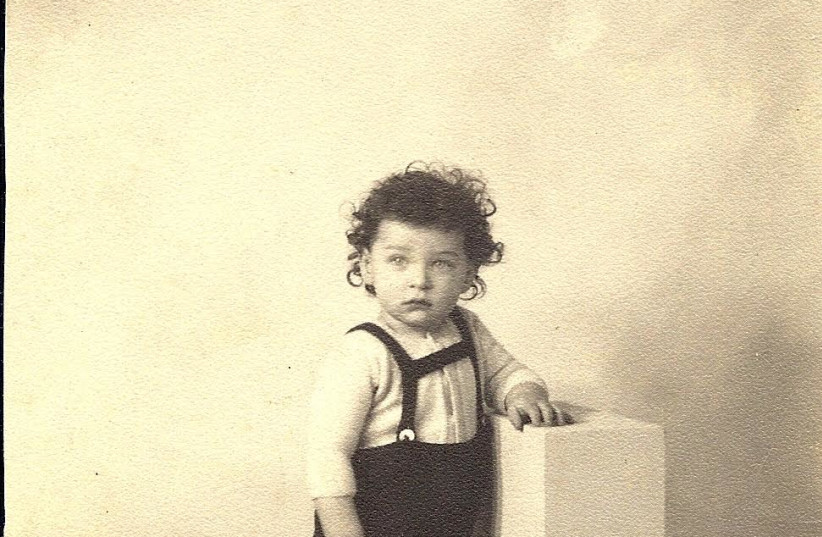

Hidden child survivor Tswi Josef Herschel was given to a Christian family when he was four months old. With International Holocaust Remembrance Day falling today, January 27, he tells the Magazine, “Although I was a little baby, my first trauma was the separation from my biological parents.”

After the war, hidden children continued to live in the shadows, forbidden from speaking about the past and eclipsed by stories of survivors of concentration camps. Herschel explains, “No one wanted to listen to us, and we needed to talk. We needed to express ourselves because it was a necessity to tell our story, our grief, but the hidden child survivors were swept under the rug… We are children of muteness.”

“No one wanted to listen to us, and we needed to talk. We needed to express ourselves because it was a necessity to tell our story, our grief, but the hidden child survivors were swept under the rug… We are children of muteness.”

Tswi Josef Herschel

The story of Tswi Josef Herschel: A hidden child Holocaust survivor

Herschel was born on December 29, 1942, in Zwolle, a town with a small Jewish community of about 800 people in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands. His young parents, Ammy and Nico, were forced to relocate to the Amsterdam ghetto that served as a collection point before Jews were deported to the Westerbork concentration camp, and then to an extermination camp afterward. They feared for their lives and the life of their child.

Nico, an accountant, contacted his close friend and boss, Piet Schwenke, who was part of the resistance, for help. Schwenke arranged for his wife and 17-year-old daughter, Christina, to smuggle Herschel out of the Amsterdam ghetto. Christina carried him in her arms – as though he was her own baby – back to their home in Oosterbeek, an eastern village in the Netherlands. Because Mr. Schwenke had just been arrested for opposing the Germans, it was too risky for Herschel to stay with them, so he was taken into hiding by the family of a friend of his, Willem de Jongh, head of the resistance of Oosterbeek, and his wife, Margje.

The de Jonghs were already hiding two Jewish teenagers, one of whom was extremely ill. They were a kindhearted, altruistic family who had five children of their own and “just wanted to save lives, “ Herschel explains. “The risk that people took for taking in Jews to put them in hiding was as high as to be a Jew in those days, and the fate of them was exactly the same, not only for one person, but for the whole family.”

Herschel spent the next three years as Henkie de Jongh because his birth name, Tswi, was a Jewish name, Hebrew for “Herman.” Later in life, he discovered that he had been named after his paternal grandfather, who had been murdered in a gas chamber in Auschwitz a few months before Herschel was born.

Herschel remembers with fondness how the de Jonghs made him feel part of their close-knit family. “I was taken care of with love. I was taken in as their own child,” he says. “My (foster) siblings were my brothers and sisters.” They were a religious Christian family, and Herschel had no idea that he was really Jewish. Herschel describes how “every day there was the Bible at the table; after lunch, they read a chapter…I was Christian, I went to church, even the prayers I know today.”

On September 17, 1944, Operation Market Garden, a famous World War II battle, commenced. For 10 days, the Allies fought against the Germans and succeeded in liberating two Dutch cities and several towns but did not fulfill their main objectives, such as liberating all of the Netherlands.

Herschel vividly recalls, “We saw gliders landing around our house, and the parachutes came down. It was a magnificent sight, to tell you the truth.” His foster father hid everyone in the basement just in time – his sisters screamed as a bomb hit the house, and it went up in flames. Herschel and the de Jonghs were evacuated to Spankenburg, a Dutch village near Amsterdam, where a charitable family offered them shelter in their home, along with other evacuees.

AFTER THE liberation of the Netherlands in May 1945, Herschel’s paternal grandmother, who had also been in hiding, showed up in Spankenburg, determined to take him back to Rotterdam with her. Herschel’s father had told her where Herschel’s hiding place was, and she hitchhiked to Oosterbeck to find him. She was shocked to see their decimated house, and neighbors informed her of where the family was staying.

Herschel never got to say goodbye to his foster parents. He felt like his entire life and everyone he loved was ripped away from him. “It was the most devastating moment and trauma after the bomb fell on our house, but at least I had my [foster] mother and father. I was snatched away; forced to go with a strange woman to a totally new surrounding.”

Herschel’s grandmother forbade him from having any contact with the de Jonghs. When he became so distraught, she recognized her grave mistake. “After six months of nagging and crying, she arranged to meet with my foster parents. Since then, I saw them more often, but it was never, ever the same.“ Herschel adds, “Up till today, I have contact with their grandchildren, and I’m still Uncle Henk, Henkie de Jongh.” The de Jongh family has been honored at Yad Vashem’s Righteous Among the Nations.

In Rotterdam, Herschel became someone else with a new name (Herman) and a new religion with a new language. Even when his grandmother was in hiding, she kept kosher, and it was crucial to her that Herschel be raised to do the same. She forced Herschel to go to Hebrew school twice a week. He describes feeling like he was living two lives. “I didn’t want to be Jewish… I came from a background that was totally different; I had to learn all these [new] things.”

Adding to Herschel’s distress were his classmates at public school who were children of Nazi collaborators. They beat and taunted him, saying he should have been gassed. Herschel remembers, “I was ‘the stinking Jew,’ ‘dirty Jew.’ I had to fight… Even my teachers were antisemites. In high school, it was the same. Early on, I went to learn Judo so I could defend myself, and then they had more respect for me.”

“I was ‘the stinking Jew,’ ‘dirty Jew.’ I had to fight… Even my teachers were antisemites. In high school, it was the same. Early on, I went to learn Judo so I could defend myself, and then they had more respect for me.”

Tswi Josef Herschel

It was a dark time of unimaginable grief for the Dutch Jewish community. Herschel describes the Jewish people he encountered, as well as his Hebrew school teachers, as being “all traumatized because they were survivors. Everyone lost their families.” Despite their anguish “the community was very resilient. They wanted to live and to build up their lives,” Herschel says.

Herschel was eight years old when he discovered that he, too, shared the terrible trauma of losing his family. He learned that he was an orphan and his birth name was “Tswi” when a family tree his father sketched came tumbling down off a bookshelf he was forbidden to look through, confronting him with a past he didn’t know existed.

HERSCHEL REVEALS, “How I found out about my real name is that my grandmother said, ‘You are not allowed to touch the top bookshelves.’ I took a chair one day and took one of the 10 diaries. My father wrote 10 diaries starting in 1932, and in 1941 he stopped. I took one of his diaries, and out fell a family tree… There was my name, and it was connected to Nico Herschel, who I knew was my father.”

It was not until he was 35 years old that Herschel could bring himself to read his father’s diary entries. “I couldn’t touch it – it was too emotional,” Herschel says. He wanted to wait until he felt strong enough to bear the immense emotional undertaking of living through his father’s wartime experiences.

Even though Herschel’s father had a heightened awareness of the perilous times they were in, his outlook remained unwaveringly optimistic, an attitude Herschel inherited. His father drew a life calendar with pictures illustrating what he believed would happen. His visions for the future were documented as though they had already occurred, and “90 percent came true,” Herschel states.

One of the pictures is captioned “In August 1964 we arrived in Israel” with a hopeful Star of David. Tiny hand-drawn Magen Davids also decorate the pages of his diary, like reminders to keep looking forward. One entry reads “A people without a country doesn’t have a future.”

Herschel’s parents were members of Naharut Israel, a Zionist youth movement in the Netherlands, and they dreamt about making aliyah. While separated for a year in 1941 due to work circumstances, they corresponded through letters almost every day. Herschel describes his parents as “already in love when they were teenagers. You can see it in the way my father writes about my mother.” They kept professing their love for each other and for their homeland. “Their hopes, their dream to go on aliyah were indescribable.” Herschel says, “My father wrote to my mother that chas v’chaliliah [God forbid], if something happens, if we’re going to be separated, that we will find each other in the harbor of Haifa. And then I stopped reading.”

The last entry of Herschel’s father’s diary, dated August 14, 1941, states, “Officials of Jewish blood [the Netherlands] are called upon to perform services in labor camps. Maybe I’ll manage to stay out of harm’s way. However, a Jew imprisoned in Europe has few chances.”

Instead of two young people in love making plans to spend the summer together with their child, in July of 1943 Herschel’s parents were forced into cattle cars with 2,200 other Jews headed to the Sobibor extermination camp. It was the last deportation from the Westerbork concentration camp in the Netherlands to Sobibor in German-occupied Poland. Herschel’s words are heavy with sorrow when he says, “All the passengers, all the Jews were gassed upon arrival.” His father was 27 and his mother 24.

Herschel describes feeling the presence of his parents guiding him like an angelic force throughout his life. “The moment I started to realize that I am an orphan, my parents were always looking from above and guiding me. Sometimes I was very alone, and I didn’t know what to do, and so somehow, I don’t know my parents, I never heard their voices, [but] there was a voice in my head saying, ‘You have to go this way to do that.’”

Herschel founded a manufacturing company which produced smooth metal parts and machinery. It was a great success. After he sold the company, he fulfilled his childhood dream to emigrate from the Netherlands to Israel with his wife in 1986, following his two daughters who already lived there. Overcome by emotion, he expresses how proud he is that his grandchildren are born in Israel and serve in the IDF.

Herschel says that for many years, he struggled to understand why his parents gave him up. It was not until he became a father himself that he truly understood it was an act of the deepest kind of love intertwined with faith and hope for the future. “I was born out of love, and out of love I was given away,” he says.

HERSCHEL BEGAN speaking publicly about his life on International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Washington, DC in 2004, where he was a candle lighter at the memorial ceremony on Capitol Hill. After he participated in an interview hosted by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Elie Wiesel approached him and said, “Mr. Herschel, we are both survivors. Your [story] is totally different than how I survived, but you can convey a message, especially for the young generation. Please do it!” Herschel has been telling his story ever since.

Herschel’s youngest daughter, Natali, remembers finding her father in his dark office with the reading light on. “I never knew what he was doing in the middle of the night,” she says. “20 years ago, when he started lecturing, I found out he was reading my grandfather’s diaries at night.”

Today, Herschel and Natali travel together across Europe and Israel to lecture at schools, religious institutions, police academies and Holocaust museums, such as Yad Vashem and The Anne Frank Center Berlin, about the dangers of antisemitism, populism and intolerance. Natali focuses on the impact of the Holocaust on the next generations.

In 2019, Herschel was awarded The German Order of Merit by German President Frank Walter-Steinmeier, and in July 2022, the German President of the Police of Lower Saxony honored them for lecturing at police academies. Herschel will be awarded with the 2022 Simon Wiesenthal Prize for his work in March.

Last year, Herschel and Natali were featured in a documentary, WiederGut (Is It All Right?), which examines how Holocaust education is taken much more seriously in schools in Germany than in the Netherlands, even though the Netherlands had the highest number of Jewish Holocaust victims in Western Europe.

They also converse with descendants of Nazis, who Natali says frequently come up to her after her lectures, crying. “They feel so ashamed… Since their childhood, it was an issue. They’re embarrassed. It hindered them in their growth; they’re frustrated, they’re angry… it’s taboo to talk about.”

“They feel so ashamed… Since their childhood, it was an issue. They’re embarrassed. It hindered them in their growth; they’re frustrated, they’re angry… it’s taboo to talk about.”

Natali

Herschel and Natali believe we are on the verge of another foreboding time. “We have to be thankful that we have our own country,” Herschel states, “because we are in this situation, and I see its gathering clouds, and when you close your eyes, then all of a sudden you wake up and say, ‘How is it possible?’”

Tswi Herschel’s website: tswiherschel.net/ WiederGut by Ruben Gischler and Tobias Muller will be available for public viewing until February 14: vimeo.com/715293206/c49be14b8b