After their honeymoon, a young couple sometimes begin to quarrel. Because it turns out that before the wedding, they didn’t really know who their spouse was. And in general, they didn’t know anything about what it means to live with a family. They didn’t know that each family has its own weaknesses and shortcomings. Principles from which no compromises are allowed. In modern society, such clarification very often ends in divorce, either de jure or de facto.

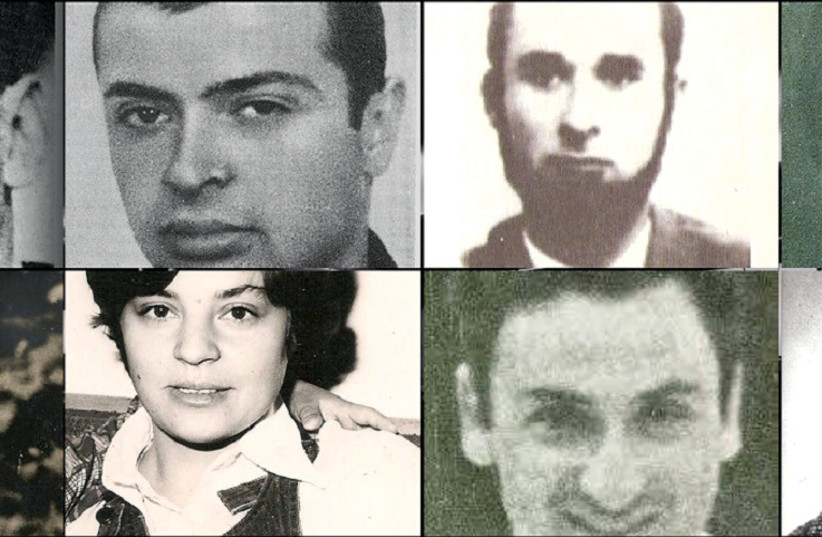

Let’s see what happened after the “Wedding” (the conditional name for the operation to hijack a Soviet plane by members of the Jewish underground movement in Russia) in 1970, later dubbed the Dymshits–Kuznetsov hijacking affair after its leaders, Mark Dymshits and Edouard Kuznetsov.

Operation 'honeymoon'

The “honeymoon” of this operation is quite well known: the arrest of its participants and accomplices; the “defeat” of the Jewish national movement in the USSR. The unexpected reaction of American Jewry was the organization of mass protests that swept many countries of the world.

The unexpected reaction of the Soviet authorities was the issuance of exit permits to hundreds of thousands of Jews. It must be admitted that such a reaction attested to the ability of the Soviet government to take a sober look at things.

They had no other choice. There, at the top, they knew something that the inhabitants of the USSR and observers from outside the Soviet Union had no idea about – the non-Soviet government was on the verge of collapse, and it could not afford a confrontation with the West. On the other hand, the Soviets believed that there were not many who wanted to leave the USSR and that the enthusiasm of the Jews of America and those who joined them would soon diminish.

The absence of national aspirations of Soviet Jews is evidenced by the fact that three to four years after the start of the departure, the “sub-advisers” for the departure began to get stuck in Austria and Italy, hoping to get to the US.

That was how the “honeymoon” after the “Wedding” was supposed to end. The struggle for exit began to stagnate.

In this situation, Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev had to “close the shop,” declaring that there were no more people who wanted to go “to the national motherland.” However, this turned out to be impossible.

Why? Firstly, due to the fact that for some reason, the enthusiasm of the Jews in the West did not diminish but, on the contrary, only grew and intensified.

It can be said that the struggle for Soviet Jews gave Western Jews an outlet for feelings of guilt for the betrayal of European Jewry in the years of WW II.

The end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s symbolized the interest of public opinion in the struggle for human rights and against war. Humanity recovered from the WW II shock. It was the fight against the Vietnam War, the fight for the rights of Blacks in the US, and so on. In this atmosphere, the struggle for Soviet Jews and their rights was an integral part of Western thinking.

Paradoxically, it can be argued that these anti-American movements, which were applauded by the leadership of the USSR, supported and financed by them, retroactively ran into the Soviet system, which, unlike the flexible Western system, was unable to withstand structural change and eventually fell apart. What happened inside the USSR? The big miscalculation of the Soviet government was the expectation that Zionism was over and the steam was released from the boiler.

Jews didn't want to go to Israel

The Jews did not want to go to Israel. But then the “first” department intervened, which was in charge of secrecy and could not deviate from the principle of “hold and not let go.”

The KGB destroyed the Soviet power. People who were refused exit permits for reasons of secrecy became “refuseniks.” The value of “secrecy” is evidenced by the case of Vladimir Slepak, who at the end of the 1950s worked in a research institute.

He said to the head of the Secrecy Office, “You do not have any secret developments that it makes sense to hide. Soviet science is 30 years behind the West.”

“Comrade,” the official answered, “that is the secret.”

Whatever it was, the West turned out to have enough reasons to continue the fight for the rights of refuseniks. And those, as intellectuals, did not sit idly by but created all kinds of scientific and cultural seminars that attracted the interest of the international press.

And besides, for Western Jews the argument that the councils could resort to saying that Jews do not want to go to Israel anymore and therefore the exit is closed would be ridiculous.

The struggle for freedom was important to American Jews. They were less interested in Zionism. Wanting to crush the movement of refuseniks, the KGB carried out repressive actions against circles for the study of Hebrew. Searches, arrests, trials provided new fuel for the continuation of the struggle.

However, here there is a contradiction between the interests of Western states, primarily the United States, and unorganized “protesters.”

The concept of the American administration was “rapprochement” and “convergence” – that is, the gradual erosion of the Soviet ideology. American leaders continued to fear the Soviet superpower, fearing that pushing the Soviets too hard might create friction again. They were against the creation of a demonstrative antagonism.

The establishment was looking for calm. The Jewish establishment in the United States, which was closely connected with the highest authorities – the monetary and political system – reacted in the same way.

At the initial stage, the Jewish establishment simply wanted to put the brakes on the enthusiasm of the masses. Their demagogy was the need to conduct “quiet negotiations” with Brezhnev. This is, they say, the only way to get something from the Russian bear.

However, the inflamed Jewish activists did not calm down.

The ideologue and founder of the movement for the liberation of Soviet Jews, Yaakov Birnbaum, believed that activism should force the establishment to accept their active policy of struggle and opposition. In his opinion, the participation of the establishment in the struggle was necessary in order to force the US administration to take a more active position.

Not being able to put a damper on the heat of the struggle, the Jewish establishment resorted to the favorite method of creating organizations that declaratively fought for the freedom of Soviet Jews, but in fact sought reconciliation with the Soviet regime.

In this they were supported by the State of Israel, which went in the wake of the American administration. In addition, Israel feared a nervous reaction from the Soviet giant, which was a major player in the Middle East theater of operations.

Israel was forced to make a decision: What is more important – the fight for Soviet Jews or the stabilization of the situation in the Middle East? And such a decision was made.

In the United States, the National Conference for Soviet Jewry was created, which, in its financial and political capabilities, surpassed self-made organizations of enthusiasts, crushing them with the authoritative opinion of “Israeli specialists.”

The controversy between organizations involved in emigration from the USSR became particularly clear during the efforts of the American administration to repeal the Jackson-Vanik amendment, which restricted trade with countries that did not allow freedom of emigration.

After the appointment of Mikhail Gorbachev as head of the USSR, American president Ronald Reagan sought to soften the relationship between the two countries.

One of the obstacles was the Jackson-Vanik amendment. Gorbachev informally asked Reagan to lift the restriction on trade. He stated that an ultimatum of this kind humiliated the Soviet Union and that it would never make concessions. On the other hand, if the Jackson-Vanik amendment was repealed, the Soviet Union would pursue a policy of free exit.

In order to put pressure on Jackson, Reagan turned to the Israeli government, headed by Menachem Begin.

However, nothing helped; Jackson did not concede. He did not believe the promises of the communists, which were violated many times. Jackson was supported by Jewish organizations for the freedom of Soviet Jews such as Student Straggle for Soviet Jewry; Public Councils for Soviet Jewry; and the organization of former refuseniks in Israel, which I headed.

Then, at the request of the Israeli government, a delegation of the American Jewish establishment was sent to the Soviet Union to meet with the refuseniks.

It is amazing that the KGB allowed this meeting to take place. Moscow refuseniks declared a resounding “no” to the Jewish establishment. The Israeli government failed to fulfill the order of the Americans. From that moment on, the refuseniks, who were not ready to submit to the will of the Israeli government, fell into the rank of enemies of state interests. As history has shown, the position of informal organizations actually met the interests of the whole world.

Faced with the tough and uncompromising position of opponents of Soviet power, Mikhail Gorbachev could no longer limit himself to cosmetic maneuvers. A few years later, the Soviet Union collapsed.

This article was translated from the original Hebrew by David Herman. ■