As we head toward Purim, the festival in which we celebrate the triumph of Queen Esther who saved the Jews from the evil Haman in ancient Persia, we look at those Soviet Jewish women whose remarkable modern-day achievements have helped shape the face of Israel today.

Not free to live as Jews, these women risked their lives to escape the Soviet Union, where they faced imprisonment for engaging in Zionist activity. Despite this, they stood up for their rights and were a beacon of hope for many in the struggle to free Soviet Jews from oppressive Soviet life.

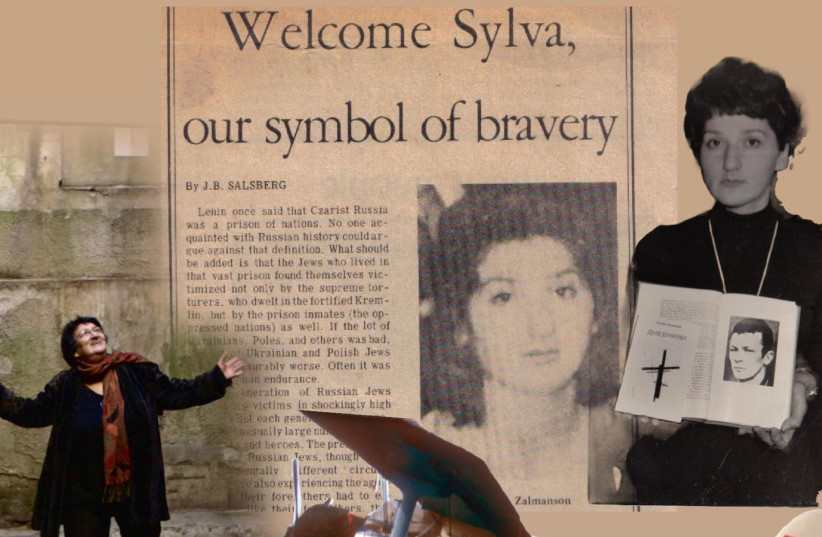

Sylva Zalmanson

Soviet-born Jew Sylva Zalmanson is one such woman. The courage and tenacity shown by this ardent human rights activist, artist, and engineer, who settled in Israel in 1974, is a testament not just to all women but to everyone who believes in “A world free of bias, stereotypes, and discrimination” (International Women’s Day website).

Born in Siberia in 1944, from a young age Sylva dreamed of living in Israel. Having been repeatedly denied an exit visa to leave the Soviet Union for Israel, she and her then-husband, Eduard Kuznetsov, joined an underground group of Zionist activists who devised an escape plan: Operation Wedding.

The group bought all the plane tickets for a local flight, as if they were going to a wedding. Once on board, they planned to take control of the plane, whereupon Mark Dymshits, a former Soviet military pilot and Jewish refusenik, would fly the aircraft under the radar and beyond the Soviet border.

Sylva was tasked with recruiting most of the group members, including Kuznetsov and her two brothers Wolf and Israel Zalmanson.

Although the group was aware that their plan had been leaked to the KGB, who lay in wait, they still went ahead with the operation.

Moments before they boarded on June 15, 1970, the group was arrested and charged with high treason. They went on trial six months later. Sylva was the only woman to be tried and the first to go on the stand, from where she spoke these words:

“If you had not denied us our right to leave Russia, this group wouldn’t exist. We would just leave for Israel with no desire to hijack a plane or any other illegal thing.

“Even here, on trial, I still believe I’ll make it to Israel some day. I feel I’m the Jewish people’s heiress, so I’ll quote our sayings ‘Leshana haba’ah be’Yerushalayim’ [Next year in Jerusalem]; and ‘If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.’”

Sylva received a sentence of 10 years in a Soviet forced labor camp. Kuznetsov and Dymshits were given death sentences; these were reduced to 15 years’ imprisonment after only eight days, due to massive world pressure.

The Let My People Go! campaign raised awareness about the group’s plight, and tens of thousands of people demonstrated all over the world demanding the release of Sylva and her comrades and for Soviet Jews to be allowed to emigrate.

Their campaign resulted in diplomatic pressure being put on the Soviet authorities, who subsequently issued visas to hundreds of thousands of Soviet Jews, resulting in some 300,000 emigrating between the time of the trial and 1979.

A secret prisoner exchange between the Soviet government and the Israeli government secured Sylva’s early release on August 22, 1974. She realized her dream and immigrated to Israel, where she worked as an engineer in the aviation industry.

Not content with her own good fortune, Sylva continued her relentless campaigning for the release of her family and friends, including a 16-day hunger strike in front of the United Nations in New York in 1976, refusing to eat to the point of losing consciousness.

Her tenacity paid off. Most of the group, including Kuznetsov and Sylva’s brothers, were released in April 1979 following a second prisoner exchange, this time with the American government.

Anat Zalmanson-Kuznetsov

Sylva and Eduard Kuznetsov’s only child, Israeli filmmaker Anat Zalmanson-Kuznetsov, who was born and raised in Israel, has always been consumed with the desire to ensure that the next generation is familiar with the historic struggle of Soviet Jewry.

Her 2016 documentary Operation Wedding, named after the foiled escape plan that landed her parents in prison, has appeared in film festivals worldwide, winning 21 awards including Best Documentary at the Chicago Festival of Israeli Cinema, and Best Feature Documentary at the International Filmmaker Festival of New York.

Anat has also continued to spread the word far and wide by producing a film of archival materials for historians about the Soviet Jewry struggle, and sharing related information through social media. Currently, she is writing the script for a series titled Functioning.

In addition, she has developed an interactive online educational program in English and Hebrew with the Prime Minister’s Office called Nativ, an independent administrative unit for Jews and their families living throughout former Soviet Union countries. The unit was set up to strengthen ties with the State of Israel and broaden knowledge about Israeli achievements, culture, and heritage.

The Let My People Go program provides lesson plans and activities for educators relating to “The Soviet Jewry Struggle, Refuseniks, and Prisoners of Zion, 1948-1991.”

It also shares stories about Soviet women and girls who faced unspeakable cruelty at the hands of the Soviet government, such as Marina Tiemkin.

Marina Tiemkin

Happy-go-lucky Marina Tiemkin, 13, was kidnapped by the KGB in February 1973 – in nothing more than her school uniform – from her paternal grandmother’s house at her mother’s instigation, after having told her she wanted to leave for Israel with her father, Dr. Alexander Tiemkin. She was flown to the Orlyonok Young Pioneer camp, a federal state camp for children aged 11 to 16 on the eastern shore of the Black Sea.

Established in 1960, Orlyonok had become a thriving hub of activity by 1973; some 17,000 children visited annually, using the camp’s facilities, which included a swimming pool and cinema.

Nevertheless, Marina felt trapped and alone there. She decided recently to confront her traumatic refusenik past and write about the first five years after her kidnapping.

“To me, the place was a prison. I declared a hunger strike, and for four days I didn’t eat anything until a man from the administration came and told me I would be force-fed.

“I was frightened but told my captors I’d stop the hunger strike if they would deliver letters from me to my father and my grandmother. They promised. Of course, they didn’t keep the promise. I wrote eight letters; not one was delivered,” she recalled in her memoirs.

Marina spent eight months in the camp before she was released. “I was returned to Moscow, to my mother’s and maternal grandmother’s house. They acted as if nothing had happened. I was afraid to talk and ask questions,” she recounted.

Her teenage years were spent under the yoke of relentless KGB surveillance and an express order not to see or contact her father – who by this time had made aliyah – or her paternal grandmother.

Nevertheless, her father did not give up on her. “From Israel, my father made repeated attempts to contact me via newspapers like The Jerusalem Post. This resulted in my receiving more warnings. I stopped talking to people I suspected were in contact with my father.”

In 1990, Marina finally realized her dream and moved to Israel with her family.

Not content simply to share Marina’s story, the Let My People Go program also suggests some “learning objectives” that may be undertaken to encourage discussion and a deeper understanding of Marina’s background and how life was in the Soviet Union for a young girl in the 1970s, as well as ways to stay true to one’s ideals under social pressure.

Avital Sharansky

Perhaps one of the more well-known faces of the Soviet Jewry Movement is Avital Sharansky (born Natalia Stieglitz in 1950 in Ukraine), who fought for the release of her husband, Natan Sharansky, from Soviet imprisonment.

The day after the couple married in 1974, Natalia (as she was known then) left for Israel, while her husband’s exit visa was denied, and he remained in the Soviet Union. Natan (then known as Anatoly) was imprisoned in 1977 on charges of high treason after a Soviet newspaper alleged that he was collaborating with the CIA. Despite denials from every level of the US government, he was found guilty and sentenced to 13 years in prison.

In the courtroom before the announcement of his verdict, Natan said: “To the court, I have nothing to say; to my wife and the Jewish people, I say ‘Next year in Jerusalem.’” This powerful slogan later became the title of his wife’s book, Next Year in Jerusalem.

After Natann’s imprisonment, the couple was thrown into the spotlight as their struggle became a cause célèbre. Avital (who changed her name from Natalia upon her arrival in Israel), campaigned tirelessly for her husband’s release, meeting with government leaders in the United States and around the world.

Natan Sharansky was released on February 11, 1986, and immediately joined his wife in Israel, after which she stepped away from public life. Having eschewed all public honors, this remarkable yet humble woman now lectures Russian-speaking immigrants in Jewish studies and gives talks about her past to young students.

Yulia Navalnaya

Only last month, were we reminded that the struggle for human rights is still very real for many Russian women. Yulia Navalnaya is the widow of Russian opposition leader, anti-corruption activist, lawyer, and political prisoner Alexei Navalny, who died in a Siberian prison on February 16, under circumstances that remain unclear.

Yulia had been a constant source of strength and support for her husband, whom she married in 2000. She campaigned tirelessly when he was urgently hospitalized in Omsk following a suspected poisoning, demanding that he be released to Germany for treatment, and even turning directly to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

After Alexei was transferred to Charité hospital in Berlin, experts confirmed that he had been poisoned. Although this was later denied by Russian doctor Leonid Roshal, Yulia was not afraid to speak out on her husband’s behalf. Roshal acted “not as a doctor but as the voice of the state,” she said.

Yulia’s unwavering support and strength undoubtedly kept her husband going. “Yulia, you saved me,” he wrote.

When the couple returned to Russia in January 2021 and Navalny was detained at the border control, Yulia made a fearless public statement in his support. “Alexei said that he is not afraid… and I’m not afraid, either. And I urge you all not to be afraid.”

Her activities, she claims, led to her own persecution “as the wife of an enemy of the people.” She wrote on Instagram: “The year of ’37 [the year of the Great Purge by Stalin] has come, and we did not notice.”

Maybe Yulia did not notice, but those engaged in the Soviet Jewry struggle certainly did.

More information about these remarkable women and their struggle can be found on the Facebook group Soviet Jewry Struggle, and at en.nativ-education.org.il.