In April, the language-learning app Duolingo added its 40th language to its program arsenal: Yiddish. A couple of decades ago, it would have been unthinkable for a mainstream non-Jewish language program to offer an expansive, comprehensive course in Yiddish. But Duolingo’s Yiddish addition only serves to reflect the increased global interest in learning a language that once had as many as 12 million speakers.

Ladino, a Romance language of Sephardic Jews still spoken by hundreds of thousands worldwide, has also garnered much interest in recent years. Ladino classes, both online and in-person, are widely available to prospective learners.

But while those two Jewish languages are enjoying a cultural renaissance, many others — ones spoken in Crimea, Baghdad, Baku and beyond, which have both miraculously survived and succumbed to tumultuous periods in world history — have remained largely inaccessible to interested learners.

This month, that’s changing.

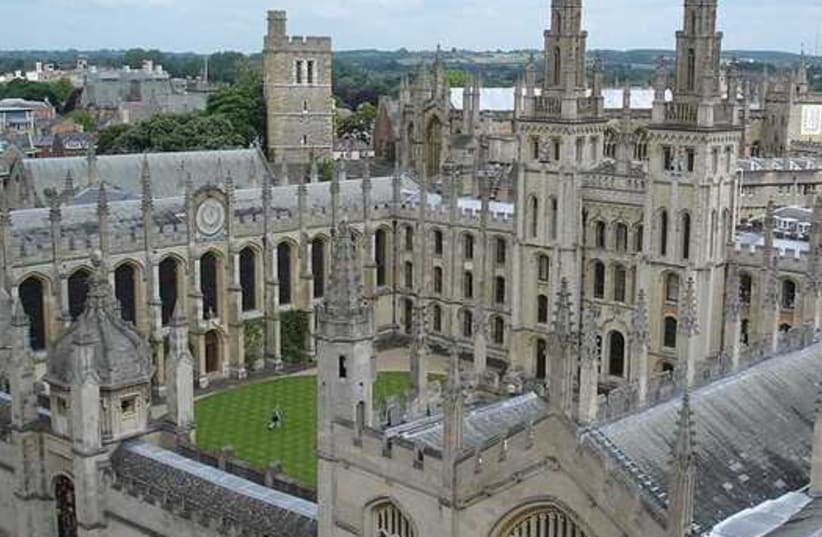

The Oxford School of Rare Jewish Languages in the UK has launched its inaugural semester of courses in 12 Jewish languages, belonging to the Aramaic, Arabic and Turkic language families. They range in number of speakers, from millions to none.

The courses, which began this week, run for an hour a week online and are free for all students.

“There are currently many brilliant research projects and online platforms concerning Jewish languages,” said Professor Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, president of the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies and the creator of the new program. “What is missing is the possibility for the growing number of interested students to learn these languages, even less in an academic setting.”

This is why she sees the OSRJL’s format — online and free — as significant: it ensures that classes are accessible to an international pool of students.

Yiddish is one of the 12 Jewish languages offered by the OSRJL — and with roughly 1.5 million speakers worldwide, it is the only language offered by the program that is not endangered or extinct. In fact, Yiddish is growing in its number of speakers.

“People outside of the Yiddish-speaking world have this distorted notion that Yiddish is disappearing,” explained Kalman Weiser, a Silber Family Professor of Modern Jewish Studies at York University, in Toronto. “It’s not. It’s only growing. Judeo-Greek, on the other hand, is a language that is going to disappear.”

Weiser’s mother speaks Judeo-Greek, but unfortunately, this tongue, which originated in the Macedonian Empire, is expected to die out with this generation without serious intervention. Most of the languages offered by the OSRJL face a similar fate. Several — including Judeo-French, Classical Judeo-Arabic and Classical Judeo-Persian — are already considered extinct.

The latter is a language that Daniel Amir, a doctoral researcher of Iranian Jewish history at the University of Oxford, aims to study at the OSRJL. He also plans to take courses in Judeo-Neo-Aramaic, a language with an estimated 60 speakers left.

“Knowing a language is one thing, but getting to learn and improve together with other people is exciting and motivating. All of these languages are ones with which I have a strong personal connection,” he said.

Amir’s family speaks a dialect of Judeo-Neo-Aramaic that is in serious decline, and he wishes to do his part to halt the downward trend. “Most of my experience with the dialect is through talking with and listening to my family, so getting a chance to formally study it is a great privilege,” he said.

Studying any Jewish language, whether it is of heritage or not, opens up a window into the diverse history of world Jewry, Weiser noted. He mentioned a theory proposed by sociolinguist Max Weinreich in “The History of the Yiddish Language,” which suggests that there is an unbroken chain of Jewish languages stemming from ancient Hebrew to today, where Yiddish is the latest link.

“Once you take this approach, any Jewish language becomes a vital part of Jewishness,” Weiser said. “You start off at one place but then you begin to see the bigger picture.”

Though the chances that Karaim (a Turkic language with roughly 80 speakers) or Judeo-Italian (a Romance language with 250 speakers) are one’s heritage language are low today, studying them can be a potent exercise in understanding the broader Jewish experience. Olszowy-Schlanger told JTA that the OSRJL intends to bolster the connection students feel to their cultures, both through the language courses and by offering a variety of other online content, including blog publications on exceptional books and a 16-lecture series on Yiddish music.

The ripple effects of a program like this are not secluded to the Jewish realm — Weiser mentioned that many past Jewish language initiatives were in tandem, influenced by, or would go on to influence other Indigenous language programs.

The faculties that raised Hebrew from the proverbial dead have also influenced the revitalization of Indigenous languages such as Lushootseed and Sami, and helped inspire the moves to preserve Irish and Cornish.

“These communities merit and deserve our research, curiosity, and admiration — both in their pasts and presents,” Amir said. “And language is a perfect point of departure.”