“Yesterday, three packages left the city… one cask with a full barrel, a small jug, and yet another small jug suckling from the barrel. Off they went, on their way to a good peaceful life without harm. And may heaven have mercy on this merchandise.”

Let us explain.

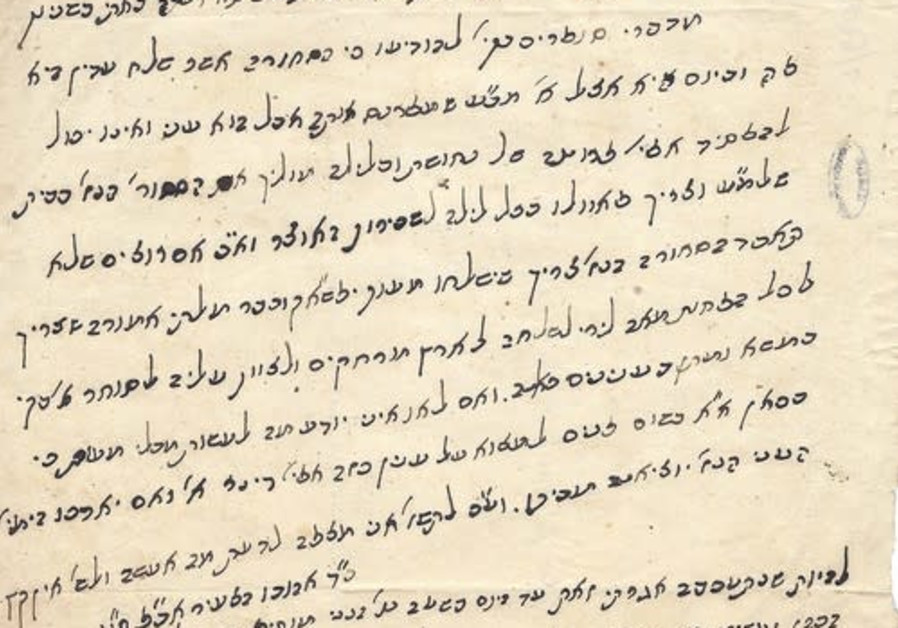

A collection of letters donated to the National Library of Israel tells the story of secretive events that took place in Livorno in the mid-nineteenth century. The letters were written by Rabbi Avraham Baruch Piperno (1800-1863) of Livorno, in response to letters from Moise Uzzielli of Florence which are not in the library's possession. The correspondence between the two men discusses the smuggling of women and their children out of Italy via the port of Livorno to various destinations along the Mediterranean coast.

On the eve of Sukkot in the year 1858, Rabbi Piperno was in Pisa for a brit milah (otherwise known as a bris, a ritual circumcision), when he received an urgent letter from Livorno about a woman in danger in the city of Florence. The letter was from Moise Uzzielli who wrote in Italian and asked Piperno to help smuggle the woman out of Italy. Piperno hastened to reply and explained to Uzzielli that his request would not be easy to carry out, “because she is a woman, and because the matter occurred in our midst, and certainly they will search for her. We will risk ourselves fruitlessly, without achieving her salvation.”

Despite his discouraging response, Piperno suggested to wait a few days and see what could be done. He also added an important instruction in his letter of reply – telling Uzzielli that, for reasons of secrecy, he should henceforth write in Hebrew and use vague language when describing the matter.

In the following correspondence, Piperno reported on the progress of the smuggling process and the technical challenges involved, giving us a rare peek into this curious historical phenomenon of smuggling Jewish women through the port of Livorno. His writings detail the existence of an entire community network that set travel arrangements and maintained contact with various Jewish communities along the shores of the Mediterranean, that served as cities of refuge for fleeing women.

The event described in the document began on September 22, 1858, and was concluded over a month later on October 28. Piperno encountered many difficulties along the way, some of which we learn about in his letters.

The smuggling plan was laid out in three phases: hiding the woman in Livorno until the day of the journey; sending her by ship to a Jewish community in one of the cities along the Mediterranean coast; and finally finding her work and a place of residence in that community. Piperno utilized his connections in Livorno and various Jewish communities to execute his plan, but he needed money to finance the operation. He asked Uzzielli to urgently transfer the necessary funds to him. In one of the letters, Piperno explains why he could not finance the matter locally. He writes: “Here I cannot take even a pence for such a thing, because they do not wish to give anything, even for our own packages.”

In keeping with his need for secrecy, Piperno refers to the escaping woman as a “package”, a very common word in a bustling port town like Livorno. We can also infer from his words that Livorno already has too many “packages” to handle. In order to clarify the state of affairs in Livorno to Uzzielli, Piperno informs him that he is already caring for a recent arrival from Rome, waiting to be smuggled out. The woman was traveling with her children and was also pregnant with another. Piperno describes the condition of the runaway in his secret code: “one cask with a full barrel, a small jug, and yet another small jug suckling from the barrel.” We can, therefore, infer that the “packages” and “barrels” reached Livorno from many places and that Livorno served as a central smuggling depot for Italian Jews.

There was a brief debate about whether to send the woman to the Jewish community of Tunis or to that of Marseilles. The decision was ultimately made to send her to Marseilles “and to connect her with a single man who will attempt to accommodate her, either in his home or in another home.” A ship would transport the woman to Marseilles. For this purpose, she would need to carry forged documents (a “transit pass” in the words of the letter). Placing a secret passenger on a ship was a very dangerous step in this process, and it was undertaken with the knowledge of the ship’s owner. In his fourth letter, Piperno reports, “Yesterday I spoke with the owner of the ship to hasten the delivery. He was waiting for a French captain to ensure that the delivery would be properly looked after.” We do not know whether the owner of the ship was a Jew who cooperated out of sympathy for his people, or whether his loyalty had been purchased by Piperno. In any event, these documents give us a better understanding of the complexity of the matter and the large number of external factors involved in the smuggling process.

After all the hardships and challenges Piperno faced in his efforts to help this particular woman, his last letter details her successful escape to safety. The echo of his sigh of relief can still be heard in his cheerful words: “Today I can say with joy and delight that yesterday evening, the package set out to the desired destination… and blessed be the Lord, who blessed us with such a great mitzvah, and may he bless all those who joined in this mitzvah with life and good tidings.”

Early evidence of a broader phenomenon

The phenomenon revealed here raises the question as to why the women were smuggled out of Italy, and if the phenomenon was unique to the period of the mid-19th century. A partial answer can be obtained from the London-Montefiore 467 manuscript, which includes copies of letters from the Jewish community of Livorno. Here we can see an excerpt of a letter sent to the community of Alexandria (around 1739-40), requesting help for a woman and her children who were whisked out of Italy for fear that their father would force them to convert:

“Our sources are speaking of a difficult and melancholy woman… She and her two sons spoke of her husband who entered into a spirit of folly and took his two sons with him in deceit and led them into the midst of the gentiles, subverting their honor without benefit, and they were almost lost… And because of the great miracle and effort of the leaders of the community… they were returned to us and he also returned with them, but there is no faith in his words…” The community acted quickly to send the children away for fear that the converters would try again.

Another letter sent to the community of Aleppo in 1754 deals with a girl who was pressured to “subvert her honor”- to convert to Christianity or to have sexual intercourse – or both. Subsequently, she was smuggled away in haste.

“She is a good girl as is her name… And she sits within the walls of her house with her mother…and the gentiles have laid their eyes on her on her to subvert her honor…She must be rushed out of this land.”

In both cases, we have no evidence as to whether the women’s trip was of a secret nature. These writings do however offer clues as to the circumstances that may have led to an urgent departure, as well as the existence of a network capable of providing immediate transport and maintaining contact with various Jewish communities. Therefore, these other incidents may also be related to the smuggling of women out of Italy from the port of Livorno in the mid-19th century.

Dr. Yakov Fuchs from the Hebrew Manuscripts Department believes he has the most interesting job at the National Library of Israel. For more stories from the National Library of Israel click here.