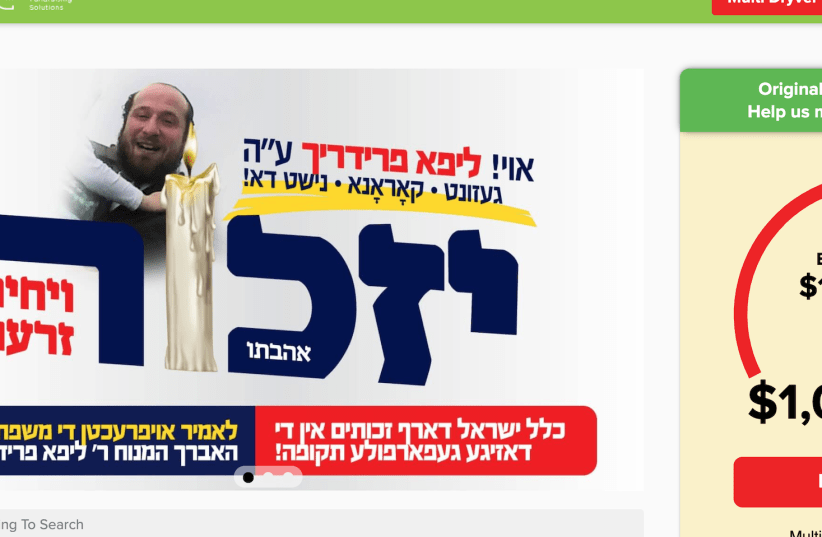

After the coronavirus killed Lipa Friedrich, a 39-year-old bus driver from Monsey, New York, in March, his wife and 11 children were left without a breadwinner.

But within days of the launch of an online fundraiser to benefit the Orthodox Jewish family, the Friedrich family faced a dramatically different financial picture. The campaign has netted more than $1 million, most within the first 48 hours, and another fundraiser brought in even more.

“We didn’t expect that we will reach such an amount,” said Shlomo Spitzer, who organized the larger campaign for the Friedrich family. “But obviously the vibe was very good. People got very involved.”

Spitzer created the campaign through DryveUp, one of several platforms used by Orthodox Jews to crowdfund for community members in crisis. While the platforms have existed for years, the coronavirus pandemic has made clear how powerful they are for generating massive amounts of donations from a relatively small community even at a time of economic upheaval.

“I’m not surprised — it has been tried and proven over and over and over again,” Moshe Hecht, the chief innovation officer at Charidy, another fundraising site, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “I am surprised that it’s still working in this environment, where people are holding onto their wallets and seemingly so frugal.”

The fundraising drives take place on a handful of crowdfunding websites that mainly serve Orthodox clients. Campaigns often feature glossy ads, emotionally overwrought copy and dramatic videos, and they are often heavily promoted on Orthodox websites that closely track coronavirus deaths in the community. Not infrequently, they manage to raise six-figure sums within days.

Donors have chipped in nearly $850,000 via the Chesed Fund for Yerachmiel “Rick” Beilis, a 52-year-old father of four from Chicago who died of the coronavirus on April 4.

In barely two weeks, 5,000 donors used Kupat Ha’ir to give over $250,000 to support the widow and nine unmarried children of Rabbi Chaim Aharon Turchin, a 48-year-old yeshiva head from Bnei Brak, Israel, who died of the coronavirus in April.

And a Charidy campaign on behalf of Yochanan Hochauser, a British father of 12 who died of the coronavirus in April, has raised more than $830,000 from about 7,600 donors.

“You have to attribute it to how people are brought up and their values,” said Yossi Klein, the founder of DryveUp. “Everybody’s cutting back on certain stuff now. No one is splurging. But for essentials, they’re still spending. So if they’re brought up that charity is essential, they still give.”

Dryveup emerged from a marketing firm, Click and Market, that Klein founded a decade ago. The site charges a flat rate to clients in exchange for a range of fundraising services, including graphic design, ad creation, video production and digital marketing materials.

“This tragedy has shaken us to the core,” reads a campaign on behalf of Baila Rivka Mertzbach, a mother of 11 from Monsey who died of the coronavirus. “The children have been left shattered, lost, and bereft of their mother’s love and warm care. ‘How will we survive the excruciating pain of living without Mommy?’ her family is weeping.”

The Chesed Fund, another popular crowdfunding site aimed at the Orthodox, charges nothing to raise money on its platform and offers a more stripped-down service, though its campaigns still routinely raise hundreds of thousands of dollars in days. Over $9 million overall has been raised on the site for coronavirus victims.

“I think it all speaks to the power of community,” said Avi Kehat, the site’s founder, who says traffic to the site has quadrupled in the last month. “Entire cities have stepped up to care for specific members who have passed away. And the broader Jewish community as a whole has also stepped up incredibly to assist individuals they have never heard of before.”

In late March, a campaign went live on the Chesed Fund for Nachman Morgan, a longtime teacher at Toras Emes Academy in Los Angeles who had died of COVID-19. Malkiel Gradon, the campaign’s organizer, said he hasn’t spent a dime promoting it, relying solely on word of mouth. Even so, the campaign is still drawing donations, creeping up past $193,000 last week on the strength of donations from about 1,450 donors — an average gift of about $133.

“When we set out the campaign, we set up an initial goal of $150,000, thinking that would be a nice dream,” Gradon said. “And we were at $150,000 in the first day pretty much.”

The ability of crowdfunding websites to raise fast cash for victims of tragedies was first demonstrated in the Jewish world in 2015, when Charidy helped raise over $900,000 in just days for the family of Nadiv Kehaty, a 30-year-old father of four who died suddenly of an apparent heart attack.

Like Dryveup, Charidy provides a range of marketing and promotional services and hosts campaigns with slick graphics, sharp copywriting, and in many cases professionally produced videos. One coronavirus campaign, for Hatzolah of Williamsburg, opens with a camera dropped from a drone onto the streets of Brooklyn and then cuts quickly among shots of masked paramedics darting from ambulances as dramatic music swells in the background. The campaign has raised over $2 million.

“We’re extremely hands on,” Hecht said. “It’s what sets us apart.”

Charidy makes money by taking a cut of funds raised on the platform, though Hecht says campaigns for individual coronavirus victims rely on a tip model in which donors agree to voluntarily pay a bit more to support the site. To date, the site has raised $3.3 million for individual coronavirus victims and another $30 million for Jewish organizations responding to the coronavirus crisis, according to Hecht.

Though it seems like easy money, organizers say raising substantial sums on crowdfunding sites takes work. The $1 million Friedrich campaign relied on over 200 people who each agreed to raise a portion of the overall target. Spitzer supplied them with graphics and messages to post on Facebook and in WhatsApp groups, and fielded their questions at all hours of the day.

“That’s the reason that a lot of charities don’t succeed. They think online campaigns are like a trick,” Spitzer said. “You put it up and it makes money. It’s not so easy like it looks. You have to work very hard. It’s a 24-hour job.”