A German Protestant minister has handed over segments of a long lost Torah scroll to the city of Görlitz in southeast Germany, 83 years after his father, a town policeman, came into possession of them.

While it is not unheard of for German non-Jews to turn over religious objects that have been lost or hidden since the Nazi period, the Torah scroll fragments took an unusually circuitous journey before coming to light last week.

The Torah had not been seen since Kristallnacht, the pogrom against synagogues and Jewish property in German-speaking lands on Nov. 9 and 10, 1938.

According to Pastor Uwe Mader, 79, the minister who turned the fragments over to the town, the story began with his father, Willi Mader. Born in Görlitz in 1914, Willi was a young police officer in training when he was called to the synagogue on the night of the anti-Jewish pogrom.

Uwe Mader told the Säschsiche Zeitung newspaper that his father never spoke about what happened that night, so it is unclear how the four Torah fragments actually ended up in the policeman’s hands. Uwe Mader believes they must have been cut out by someone who could read the Torah and carefully selected certain passages, including the creation story and the Ten Commandments.

The fragments changed hands several times over the years of Nazi and later Soviet rule.

In the late 1930s, Willi Mader brought the parchments for safekeeping to a friend in Kunnerwitz named Herta Apelt and her brother. They in turn brought them to their local pastor, Bernhard Schaffranek, who was installed in June 1940. Schaffranek hid the Torah parchments in his library. He died in July 1949. In 1969, his widow, Magdalena, handed them to the new vicar in nearby Reichenbach, Uwe Mader, likely knowing that it was his father who had first received them in 1938.

Magdalena Schaffranek told Uwe Mader to tell no one, and he kept his promise, not even telling his wife. He hid the parchments inside rolls of wallpaper in his office. When he moved to Kunnerwitz in 1977, he took the scrolls with him.

With the political turmoil of 1989 leading to German unification, Mader moved them to a locked steel cabinet, and kept the key with him at all times. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that Willi Mader finally told his son how he had begun this chain of handovers.

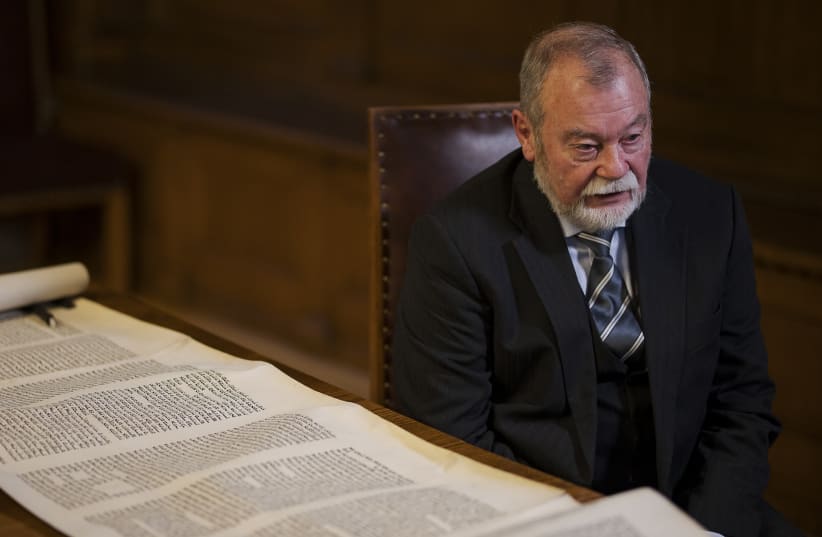

After decades of telling no one, last week Uwe Mader finally decided that the time had come to bring the parchments to light.

The city of Görlitz, which recently completed a refurbishment of its synagogue, said it plans to work with regional Jewish leaders to develop a plan for how to display, or potentially restore, the fragments.

Görlitz’s “New Synagogue,” which dates to 1911, is the only one in the state of Saxony to survive Kristallnacht. It was rededicated as a house of worship and space for interfaith gatherings last summer. There are reportedly some 30 Jews currently living in Görlitz.

Some local Jewish leaders and activists were angered by the announcement that the fragments had been given to the city rather than directly to the representatives of the Jewish community, which would be the legal successor.

But Zsolt Balla, state rabbi of Saxony and Germany’s first post-war Jewish military chaplain, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that he was optimistic about plans for the scrolls after speaking with the town’s mayor, Octavian Ursu, on Friday.

“We will be discussing strategies next week on how to proceed,” Balla said.

According to the Säschsiche Zeitung, observers were awestruck as city archivist Siegfried Hoche placed the four fragments on a table at the city hall on Thursday.

Ursu said in a statement that he was “grateful to have received such a valuable historical treasure for our council archive” and that the city would “prepare its exhibition for the public in close consultation with Jewish representatives of Saxony.”

The governor of the State of Saxony, Michael Kretschmer, said the fragments were “like a door into the history of Görlitz of the past decades, which is now opening.”

Local Jewish community chair and cantor Alex Jacobowitz viewed the parchments on Friday. He told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that some of them appear to be “in relatively good shape, and could be used in a future Sefer Torah… others are no longer usable, and should either be buried in a genizah or put into a permanent exhibit inside the Görlitzer Synagogue.”