The museum began on the grounds of a Reform summer camp in Utica, Mississippi in 1986. The new building will feature 9,000 square feet of exhibit space containing history and artifacts from 13 states, including Kentucky, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee and North Carolina. Maryland will not have exhibits in the museum as it has its own Jewish museum already.

New Orleans was chosen because it has "a great tourism economy" and "a rich Jewish history," explained Kenneth Hoffman, the executive director of the museum, to the Forward.

Hoffman visited the museum when it was still at the Mississippi summer camp. “The cabins were not air-conditioned, but the museum was,” said Hoffman, a former camper and counselor at the URJ Henry S. Jacobs camp. “So it was always a popular destination.”

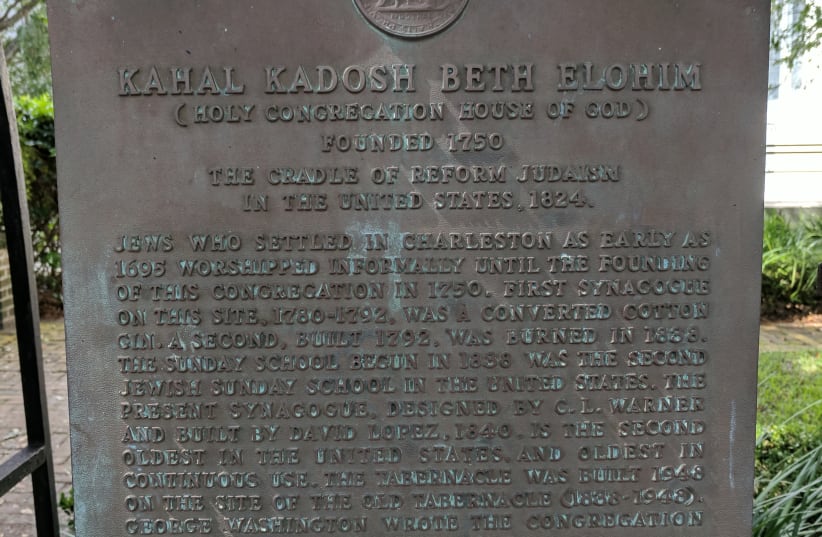

Each state represented in the museum has a unique Jewish history, but tends to diverge from the early Jewish American experience that northerners may know of.

Jews in the early south largely found work as merchants. Only making up around 2% or less of the communities they moved into, Jews had an outsized influence, becoming active philanthropists and even mayors.

Southern hospitality was and still is a large part of their lives.

"A lot of people would think that the South would be inhospitable to Jews, and in many cases the reverse is true,” Hoffman said. “The South is a very religious part of the country and Jews are considered people of the Book — we’re the originals, we’re the Old Testament people and so there’s a certain reverence for that.”

The museum will cover the whole of Southern Jewish history, with artifacts such as a still-corked pre-Prohibition saloon jug from Mississippi and a 1840s Hebrew and French prayer book that belonged to an Alsatian immigrant to Donaldsville, LA. More modern stories will also be featured, such as oral histories from Holocaust survivors who moved to the South and Jewish members of the Civil Rights movement, according to the Forward.

The museum is looking for more artifacts and stories from the broader Jewish and non-Jewish community, especially from the Carolinas, eastern Tennessee and Kentucky. "We would love to get that patch that’s signed by George Washington to a Jewish soldier if such a thing exists,” said Hoffman.

Despite a rising trend of antisemitism in the United States, the museum is not political. "We’re building this museum for the long run and so who knows what the landscape will be in five years, 10 years."

The original museum began as a warehouse for disappearing Jewish communities, with parents of campers donating objects from sold synagogue buildings, according to Hoffman.

“Even though the small towns are disappearing, it’s not a story of decline,” said Hoffman. “It’s a story of evolution and change, and that’s a big part of what Southern Jews are always dealing with, which is ‘How do I fit into this society?’ and making choices. That’s what gives our story universal appeal.”