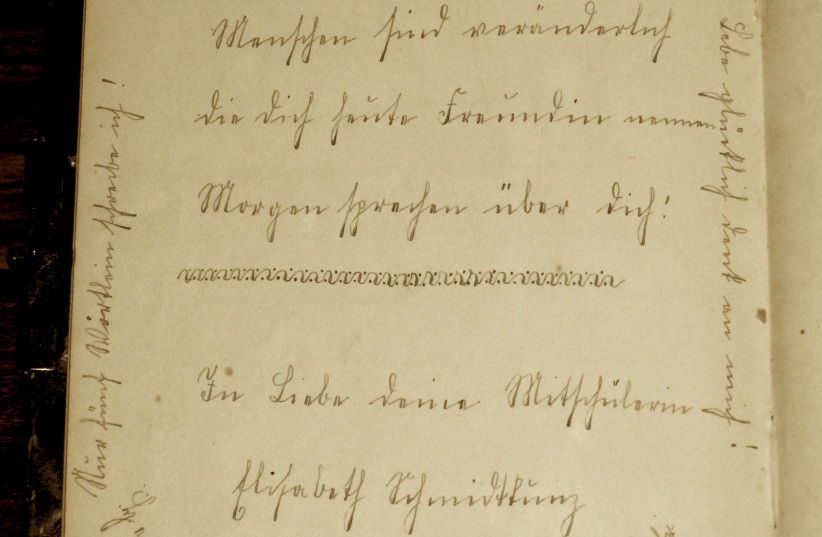

In 1916, in the picturesque German village of Heinebach, a 14-year-old girl named Elisabeth Schmidtkunz penned a sweet message in her classmate Jenny Katz’s autograph book.

“Jenny! Get to know people,” wrote Elisabeth. “People are changeable. Some who call you a friend today, might talk about you tomorrow! With love from your classmate, Elisabeth.”

One hundred and five years later, Elisabeth’s 84-year-old daughter Johanna was astonished to read her mother’s words for the first time. “It was a very special joy and surprise for me,” she said in German. “The sight of that page touched me very much.”

Jenny Katz Bachenheimer was my grandmother. Jenny’s autograph book, known in German as a “Poesiealbum,” accompanied the family when my mother and grandparents escaped the Nazis in the 1930s, ending up in New York City.

Half a century later, as she was moving out of her apartment in the then heavily German-Jewish neighborhood of Washington Heights, Oma (Grandma) Jenny handed me the Poesiealbum. She died in 1998, at the age of 95, and this teenage memento has always intrigued me, filled as it is with nearly two dozen pages of clever notes, poems, colorful stickers and intricate designs from friends and relatives, all long gone.

And now, thanks to two German scholars who have spent years researching the custom of “Poesiealbums,” my curiosity has been rewarded with their insights into what they say is one of the rare such albums by a German Jewish girl to have survived the Holocaust.

Earlier this year, in a Facebook group dedicated to the German-Jewish community, I noticed a post by Dr. Stefan Walter, whose doctoral thesis focused on the tradition of “Poesiealbums.” “Autograph books from German Jews are very rare, due to the Holocaust, and little explored,” he wrote. “I’ve created a collection of Poesiealbums for research and teaching purposes, and no albums of Jewish women are yet included. I’m looking for owners of these kinds of books.”

As a longtime chronicler of my family’s history, I couldn’t resist. Stefan and his life partner Katrin Henzel both work at the Carl von Ossietzky University in the city of Oldenburg, and we made a deal: They would interview me about Oma Jenny’s life and translate the pages, and I would interview them for this story.

The couple, both in their 40s, provided some Poesiealbum background. “This tradition began in the 16th century,” said Katrin, a lecturer at the university. “It started originally with adult students and scholars, who would travel around. They would ask professors and important people in the towns they visited to inscribe something as a souvenir.”

In the 1800s, she continued, “It changed into a tradition for young girls, first by Protestants, and later picked up by Catholic and Jewish students.”

Katrin and Stefan analyze how the content and attitudes of the messages evolve over time; they’ve perused Poesiealbums compiled during the Nazi era, and post-war, pre-unification entries from East and West Germany.

But Oma Jenny’s album was their first from a Jewish girl. “It’s very valuable for us,” said Stefan. Katrin added, “In normal times, people hand books and souvenirs down to the next generation. But the Holocaust interrupted that tradition in Germany. That’s why this is such a treasure, not just for you and your family, but for scientific reasons. This is a rare gift that you have here.”

Most of the entries in my grandmother’s album are signed with the date, followed by “1916, Kriegsjahr,” the “year of war” — that is, World War I.

There are religious admonitions: Jenny’s father Baruch, the unofficial leader of the Heinebach Jewish community, implored Jenny to “often pray to God with a believing mind. Bring praise and thanks to Him for the kindness with which He has guided you. Pray often when you are lacking comfort; it gives strength to the weak. And be willing to do good.”

Uncle Abraham Nussbaum urged her to “always hope and wait. Remember God’s word, which is our only shelter that protects and preserves.”

Most of the messages are more typical of the lighthearted rhymes then popular with teenage girls. Jenny’s friend Lotte Speier wrote, “As many thorns on a rose, As many fleas on an old buck, As much hair on a poodle, So many years you should stay healthy.” Another pal, Berta Sommer, wrote, “Live happily and healthy until three cherries weigh one pound!”

There was a darker, perhaps prescient suggestion from Jenny’s beloved cousin Wilhelmine Goldschmidt: “When you’re in a murky place, And you think you must despair, Think of the words of Kaiser Friedrich, ‘Learn to suffer without complaining.'” Another favorite cousin, Selma Nussbaum, wrote, “Be like the violet that blooms in secret. Be pious and good, even if nobody is looking at you!”

To my delight, however, there is one final entry written at the end of 1933, when the family’s financial life had collapsed due to the Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses, and at a time when they were under frequent physical attack by gangs of Hitler Youth in Heinebach.

In the midst of the growing horror, my grandfather wrote a poem to his wife Jenny, whom he married in 1928. Opa Siegfried died suddenly when I was a toddler, and although I knew he was deeply loved by many, nobody ever mentioned he was a romantic. But there were these verses from him — a complete revelation to me:

Gentle as the dawn, Awakened in young spring, And on the flower beds, The delicate rose laughs.

So you walk with blessing, And always cheerfully, On the paths full of flowers, Of your long life.

After receiving the translations of the pages, I noticed that at least eight of the writers, including Elisabeth, had clearly non-Jewish names. It was heartwarming to discover that my strictly Orthodox grandmother had close gentile friends, and it occurred to me that descendants of those women might still live in the village.

I asked a non-Jewish former neighbor, whose parents and grandparents had been particularly close to and protective of the Bachenheimers, if she knew any of the families. Irmgard Häger, who has graciously hosted my family on our visits to Heinebach in recent years, was happy to help, especially after seeing the precious keepsake herself. “I was delighted to read these poetic thoughts in old German script from these young girls,” she wrote to me several months ago. “I know from my parents that everyone loved your Oma Jenny, and you can feel that in the lines.”

Oma Jenny’s friend Elisabeth, Irmgard told me, was born in 1902, as was my grandmother. Elisabeth died in 1984. In 2021, Irmgard showed Elisabeth’s daughter Johanna Dippel her mom’s handwritten thoughts, at her home just blocks away from where they were inscribed. After expressing her joy and surprise at this unexpected missive from the past, Johanna e-mailed me, saying “My mother must have loved Jenny very much; she expressed it by decorating the page. The verse she quoted also contains a great truth. I’m very happy that my mother was able to express her feelings in this way, at such a young age.”

On the sides and corners of her page, Elisabeth added a bit more, writing “Live happy, think of me!” and, “Forget me not.” Thanks to Jenny’s Poesiealbum, now part of the digital collection of a German university, we remember them both, today and forever.