The quarrel

In 1952, the New York-based Yiddish monthly Yidisher Kemfer (The Jewish Militant) published the first prose work by then-noted Yiddish poet and Holocaust survivor Chaim Grade (pronounced Grahdeh) titled “My Quarrel” with Hersh Rasseyner.

It tells the short stoy of an ex-yeshiva bochur, Chaim Vilner, loosely representing the author himself, who has a three-part argument with a friend of his from yeshiva, Hersh Rasseyner, at three points in time: 1937, 1939, and 1948. Vilner has turned away from the halachically committed lifestyle and is instead a Yiddish poet, while his friend remained Orthodox.

The story was immediately recognized as “quite stunning,” Prof. Ruth Wisse, iconic Yiddish scholar and professor, told The Jerusalem Post ahead of the printing of her fresh translation of the story, including a storied introduction. Both were published online in Mosaic in December 2020 and will be printed by Koren’s Toby Press.

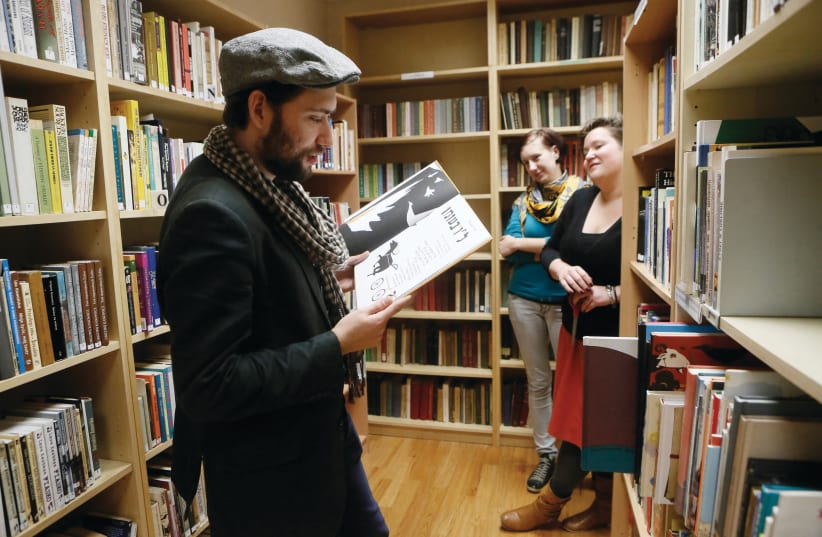

On September 12 Wisse sat down with Jewish history professor Dr. Asael Abelman at Beit Avi Chai, the Jerusalem-based thought and cultural center, to discuss the story ahead of the printing.

“The old translation took certain liberties with the story” prompting a new one from Wisse.

“That’s the power of literature,” she said. “A story lies there inert – [mere] squiggles on a page. When it is studied and read it becomes this medium through which we can study and analyze these ideas.”

The debate which Vilner and Rasseyner have is a “serious [and] intense [one],” Wisse explained. “Nevertheless, the way in which this story and debate work really hold things together.

“It is a very exciting story and very much about the questions that one had to ask after the Shoah: it brings the two sides of a major Jewish debate, particularly in Israel.”

The two sides? “To put it into a sound bite: These boys were once in yeshiva together. One left to become a Yiddish poet, and then they met. It is a very harsh break between them. One of them remains halachically [committed] while the other, who speaks as the narrator and is based on Grade himself” chooses the secular path.

Poised after the greatest display of human cruelty – the Holocaust, “One asks: ‘How can you go on believing in God and being a halachic Jew?’

“ ‘How in the world can you go on believing in man, in Western civilization?’ is the retort.”

“ ‘Quarrel,’ ” Wisse said, is a “delicate” translation of the original title. “‘Mayn krig mit hersh rasseyner (My war with Hersh Rasseyner)’” doesn’t translate to ‘quarrel,’ it translates to ‘war.’”

Grade based this story on his own experience, and is therefore the implied narrator of the story, Wisse noted: “He puts his own struggle into the form of this dramatic dialectic.

“The way the story is constructed is [designed] to show us that this is an ongoing argument, that the Shoah did absolutely nothing to change it.”

That’s a very strong statement.

“That’s my interpretation of the story. It intensifies the debate because [now] more is at stake. But they spend absolutely no time talking about their losses or experiences, everything that Holocaust commemoration [typically] does. They simply return to the same argument.

“That’s what gives the story so much power – that is the real hiddush (innovation) of the story.”

Doesn’t that, in essence, push the argument even further away from any sort of reconciliation – if you say that even after the worst exhibition of God’s treatment of man and man’s treatment of man, that the debate continues.

That is [exactly] why at the end, the only thing that Vilner really says to Rasseyner is: “May we both have the merit of meeting again in the future and seeing where we stand. And may I be as Jewish then as I am today. Reb Hersh, let us embrace...”

The impact

What do you make of that?

“What do you make of Israeli-Judaism? Is this not the debate within the Jewish people? Israel as a country shows you that this debate can be sustained within a [society].”

In her discussion with Abelman, Wisse said: “He [Grade] did not want to take the story in the direction of a political-national resolution.”

The issue, she explained, is as follows: Are the Jews are going to continue as a secular people or as a halachic people?

“He [Grade] really felt that he was presenting us with an argument that continues, that we dare not lose sight of, that we have to have the strength to take [it] seriously, and to air it, to understand what’s at stake on both sides,” she added. “I’m not sure the story has a resolution of any kind.”

Wisse’s growing awareness of the political realities around her, on a personal, communal and nationalistic level, culminated in published works on politics, one of which is titled Jews and Power, but translates in Hebrew to “The Paradox of Jewish Politics.”

“The paradox is of enormous success and enormous vulnerability,” she told the Magazine.

“The question of Jews and power boils down to whether a God-inspired and morally constrained people can hold out until the surrounding nations accept the principle of peaceful coexistence,” Wisse wrote in the Sapir Journal in August.

“Israel – the same as the Jews – only wants to be accepted by the surrounding nations. But when that doesn’t happen – what do you do? Not just militarily, but psychologically, sociologically? What do you do? How do you protect yourself against destroyers?” she asked.

“What the Jewish people did in the 1940s was the most miraculous thing that has ever happened – both in Jewish history and in general history. I don’t think there’s another example of [a] people who, in one decade, underwent what the Jews experienced in Europe – wiped [off the continent] in five years – these brilliant, magnificent, intelligent people – What is that? How in the world does anybody let that happen?

“In the same decade, the Jews recovered their sovereignty in the Land of Israel, which was under foreign domination for 2,000 years. Is there another case in history where you can imagine a people creating everything the Jews created in Europe over a millennia – being destroyed that way – [while advancing to] create the infrastructure, the strength, genius and resilience to rise again as a nation in our homeland; this is truly extraordinary.

“The Jewish people have succeeded in crafting a civilization as good as one could hope for. For me, it’s the political-human miracle, [which is] far greater than anything. It is the religious civilization that allowed for the political miracle.”

The US, Wisse added, is grappling with a similar issue now. Particularly – right around the anniversary of 9/11 – the “extraordinary debacle” that was the withdrawal from Afghanistan.

“The way the Taliban, Hezbollah – the enemies of America – see it [is like this:] This country can’t fight to save its life.”

Wisse’s suggestion? “You have to devote at least as much of everything to defending yourself against those who are going to attack you as you do in building everything that you want to enjoy.”

The memoir

Wisse’s upcoming memoir, Free as a Jew: A Personal Memoir of National Self-Liberation condenses and conveys the bizarre, wonderful sensation of realizing that you lived through history.

“I never thought that what I was experiencing mattered in history, because everything momentous was happening everywhere else – happening in Europe, where I was born – or happening in Israel,” Wisse explained.

“I later on realized that what I was experiencing was important to record.”

Wisse had begun writing personal essays years ago, serving as a precursor to the memoir.

In the work, published in September, she traces her life in its greater context of Jewish culture and politics. Wisse had begun studying Jewish studies in the US, something that wasn’t very common for women to do at the time, taking part in that revolution.

And, of course, “the miracle of the decade that was the 1940s. I want to get across how important it is – how important it remains, how much it needs to be understood and protected.

She is the Martin Peretz Professor of Yiddish Literature and Professor of Comparative Literature (emeritus) at Harvard University – “that is not something that happens every day.”

Wisse retired from Harvard in 2014 and has since been heavily involved in The Tikvah Fund, an educational institution focused on raising the next generation of Zionist leaders.

“For all that has come to me, this book is really about gratitude – for having been alive during this period of Jewish history. I was born in Europe in 1936 – how many children who were born then and are alive today to talk about it?

“My life turned out to be a more interesting story than I would have imagined.”

The memoir was published on September 21 and is available for purchase on major platforms.