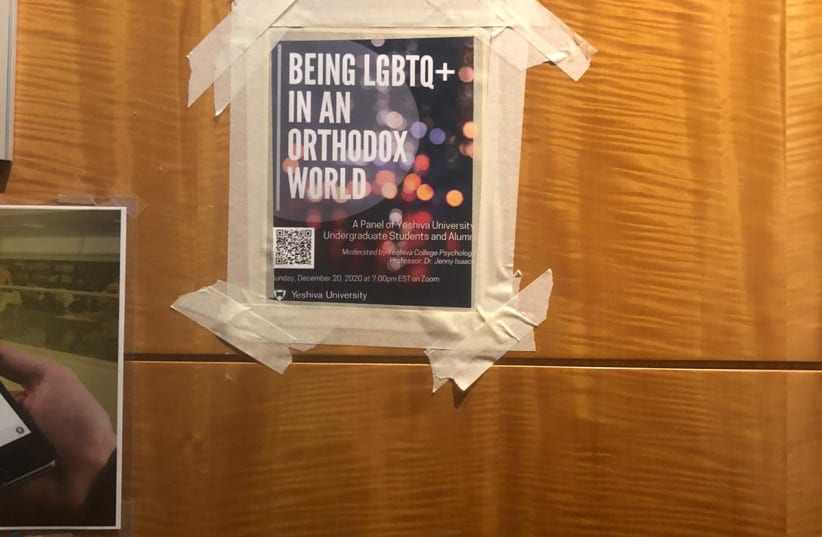

The students who helped plan the event set for Sunday say they do not want their names associated with the panel out of concern that it could have negative academic, personal or professional consequences in the Orthodox world. One said he saw rabbis at the school tearing down flyers promoting the virtual event and filed a federal discrimination complaint against the school as a result.

Dr. Chaim Nissel, Yeshiva’s vice provost for student affairs, said the school does not comment on discrimination complaints because of privacy concerns. He declined to comment on the incident but said “there is more work to be done” to make the school a “compassionate and respectful campus” for all students.

The school has said it wants to foster “an inclusive community” but has rejected several other efforts by students to organize LGBTQ events or groups on campus. This time, the student organizers secured an official faculty sponsor, hoping for a different outcome.

That sponsor, psychology professor Jenny Isaacs, said the process to gain the university’s approval had been “arduous” but that she had taken on the task because she had seen the impact of having gay students feel supported during and after the 2009 event.

“There aren’t many moments in life when you are asked to take on some risk in order to do the right thing, but this was one of them,” said Isaacs, who has taught at YU since 2005 and has tenure.

Zipporah Spanjer, a senior at Stern College for women who identifies as queer, said she was surprised that Isaacs had prevailed. “Last I heard it was going to be run unofficially,” she said. “In the past, getting any LGBTQ event approved by the university has been like pulling teeth.”

The 2009 event, colloquially known at YU and in Orthodox circles as “the gay panel,” was a watershed moment for Modern Orthodoxy’s flagship institution. While non-Orthodox denominations of Judaism now embrace LGBTQ members, Orthodoxy remains hesitant to do so because of the Torah’s edict against homosexuality.

So a live event featuring four students and graduates who identified as gay was a departure. Hundreds of people packed into the university’s largest auditorium for the panel, and at least 100 more had to be turned away, according to news reports from the time. On the panel, three alumni of the university and one then-current student described their personal experiences of being rejected, stigmatized and isolated within their Orthodox communities of origin because they were gay.

At the time, a significant threatened to withdraw part of a $30 million donation toward a new learning center on YU’s uptown campus if university leaders allowed the panel to take place, according to email exchanges from 2009 and 2010 obtained by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Afterwards, the donor accused one of the panelists of having “committed a horrible chilul hashem [desecration of God] in public, which is a grave sin in the eyes of the G-d of Israel, and its people,” according to one email.

While university administrators allowed the event to proceed, they issued multiple statements in the days afterwards distancing themselves from it.

“Homosexual activity constitutes an abomination,” the school’s five top rabbis said in one statement. Then-president Richard Joel and Yona Reiss, then dean of the rabbinical school, issued a separate statement saying that public events must be clear about what halacha, traditional Jewish law, says about homosexuality.

“Sadly, as we have discovered, public gatherings addressing these issues, even when well-intentioned, could send the wrong message and obscure the Torah’s requirements,” they said.

The statements ground to a halt whatever momentum some students felt around YU becoming a more welcoming environment for gay students. In more recent years, some students have reported an atmosphere of increasing tolerance, including from Joel, but the university’s policies have remained firm, and student efforts to advance inclusion have met roadblocks.

In September 2019, the school denied students a permit to hold a Pride march on campus; about 100 marched nearby instead. Spanjer said she hung flyers afterwards in the main building of the women’s campus with mostly anonymous quotes from LGBTQ students describing the difficulties they faced on campus. Within two days, all the flyers had been removed, she said.

In February, seven student activists filed a complaint charging discrimination with the New York City Commission on Human Rights. The case is ongoing.

And this fall, the university denied club status to a gay-straight student alliance on campus, meaning that the group would need to meet off campus. At the same time, the university announced policies it said was meant to make LGBTQ students feel more included.

Spanjer said she filed a federal discrimination complaint with the campus Title IX coordinator, in keeping with federal regulations that require schools to put in place procedures for students to file complaints of description based on sex or sexual orientation. She said she learned earlier this month that an investigation had concluded that the complaint was unfounded.

Isaacs said she was able to convince university authorities to allow the upcoming event only by emphasizing that it is intended to “alleviate the negative outcomes associated with LGBTQ youth who do not have social support,” not tell students that it is OK to be gay.

“There were definitely moments when we thought the panel wasn’t going to happen,” said Isaacs, who said she filed the initial request for the event with the dean’s office in early November.

“There is still tension between many of those with religious authority and the student body,” said Isaacs, who said the “hesitancy” she confronted at first was “soothed by reiterating that the panel is not a conversation about religious values, or even about the university’s values, but a forum to support students and further the university’s goal of inclusion.”

Since announcing the event earlier this month, student volunteers say they have received a positive response from students but a muted — and at times outright negative — response from university faculty.

One student organizer told JTA he witnessed two different faculty rabbis ripping down flyers he hung up on the uptown campus to publicize the event. (While most classes are taking place virtually due to COVID-19, the uptown yeshiva is persevering with in-person Talmud study.)

The student, who requested to remain anonymous to avoid backlash, said he confronted both rabbis personally before reporting the incidents to a university administrator and filing two Title IX complaints. He said the administrator declined his suggestion to send out a university-wide email or take any public stance condemning the flyers’ removal.

“I would expect this kind of thing from some of the faculty rabbis, but it’s more concerning to me that the administration wasn’t willing to do anything about it,” the student said.

Nissel, one of the administrators whom the student said he made aware of the flyers’ removal, wrote in an email that YU is “striving to create an understanding, compassionate and respectful campus for all our faculty, students and staff.”

“There is more work to be done and we are continuing to design programs and convene conversations to deepen the respect and compassion that is the hallmark of Torah character and community,” Nissel said.

Rachael Fried, the executive director of JQY, a nonprofit organization that supports Jewish LGBTQ youth, said compassion is not sufficient for LGBTQ students. Research shows that LGBTQ young adults who do not feel supported are at elevated risk for depression and suicide.

“YU is taking some steps in the right direction. But it’s not enough to say you’re a safe and welcoming space, you have to prove that with actions,” she said. “You have to work to build the trust of a community that has been systematically rejected for so long.”

It is “telling,” Fried said, “that students are not comfortable with their names being associated with this event.”

Spanjer said she understands why so many of her fellow students did not want their names associated with the upcoming event. “It’s the same reason a lot of LGBT students are not out publicly,” she said. “They’re worried about the response from family, friends, and the possibility of discrimination from future employers.”

“I’m OK being out, but I understand that’s a privileged attitude,” she said. “Many don’t have the luxury of a support network. Quite frankly, that’s what the panel is about.”

Student organizers say they have reasons besides fear to keep themselves out of the spotlight before the event, during which one panelist plans to come out publicly for the first time. “The event is not about me,” one student said. “It’s about any student on campus who could be going through this.”

Some Orthodox LGBTQ advocates say the event’s very existence suggests that the university has come a long way.

It’s an “undeniable sign of progress,” said YU graduate Mordechai Levovitz, who was on the 2009 panel and said he faced an intense backlash afterwards, including having his social media accounts hacked. “We can celebrate this while still saying we can do better.”

Levovitz now works as JQY’s clinical director. Reflecting on what has changed at his alma mater since his appearance on the contested 2009 panel, he said “back then, it was a chiddush that there were gay people at YU,” he said, using the colloquial Talmudic term for a novelty or discovery. Today, he said, it is “still dangerous, scary and problematic to be an LGBTQ person at YU,” even as there is more openness around the topic.

“That’s why it’s so important to have another panel like this, so fellow students and faculty understand what it’s like to be queer on this campus,” Levovitz said.