Underneath Yellowstone National Park, a lava-filled river flows. This river is likely to erupt - but when, and what can spectators do to prepare for a disaster of the sort?

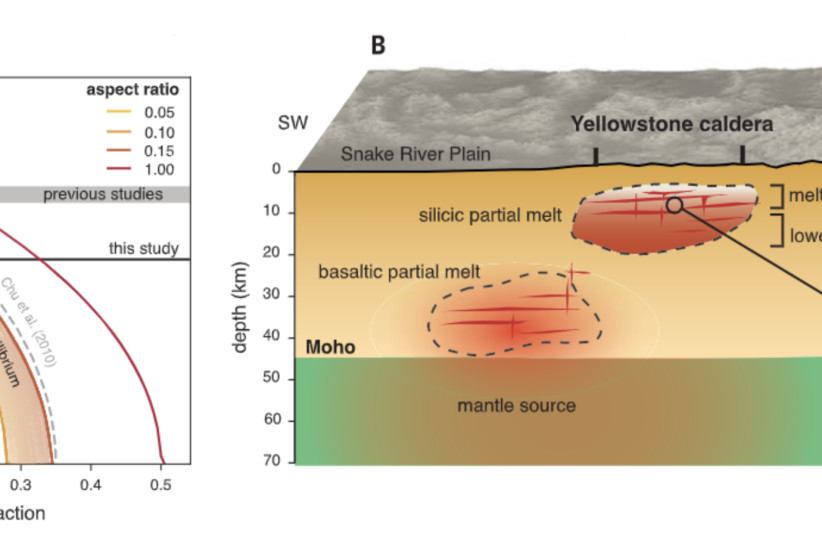

The Yellowstone caldera’s magma reservoir contains partially melted earth's crust. The extent of the melt was far more than scientists were expecting to see. This extensive melt had been enough to convince scientists that they were dealing with a conductor - magma in such a volume that it could incite other eruptions to come.

According to a new scientific study, scientists have been able to improve the model of the supervolcano and all of the associated hazards in order to properly prepare for any natural disasters of the eruptive nature in the coming years.

One rather difficult issue with assessing hazards that come with volcano eruption is that it is difficult to identify just how much magma is boiling under the surface. Plus, add in another key question - where exactly is this magma, and how can we keep ourselves safe against it?

"Although it is clear from geophysical observations that the modern Yellowstone magmatic system remains active, questions persist about the volume and distribution of melt and how it compares with conditions that preceded prior eruptions," Yellowstone researchers from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, the University of New Mexico, and others expressed in a recent study.

Threats beneath the surface

Though many studies have produced images of the subsurface below Yellowstone, revealing magma reservoir in the mid to upper crust, it is still hard to pinpoint exactly which point of the surface is the most at-risk of eruption.

"Yellowstone is an active supervolcano that will cause mass destruction when it next erupts," researchers wrote.

At this point in time, researchers believe there is not quite enough magma boiling that would bring an eruption to end all eruptions. Instead, they believe the amount of magma currently boiling is minimal, compared to what they would have previously anticipated.

Scientists say that the amount of partial melt under the surface "could be greater," so does that mean we're in the clear?

Not quite.

“[T]he uncertainty about how melts are distributed means that more melt is not necessarily more hazardous,” writes Kari M. Cooper of the University of California - Davis, in a related reflection of this study. “The results of Maguire et al. do not indicate that an eruption is more likely than previously thought.But continued monitoring of the subsurface is important as it should provide a clear picture if the situation begins to dramatically change."

The Environment and Climate Change portal is produced in cooperation with the Goldman Sonnenfeldt School of Sustainability and Climate Change at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. The Jerusalem Post maintains all editorial decisions related to the content.