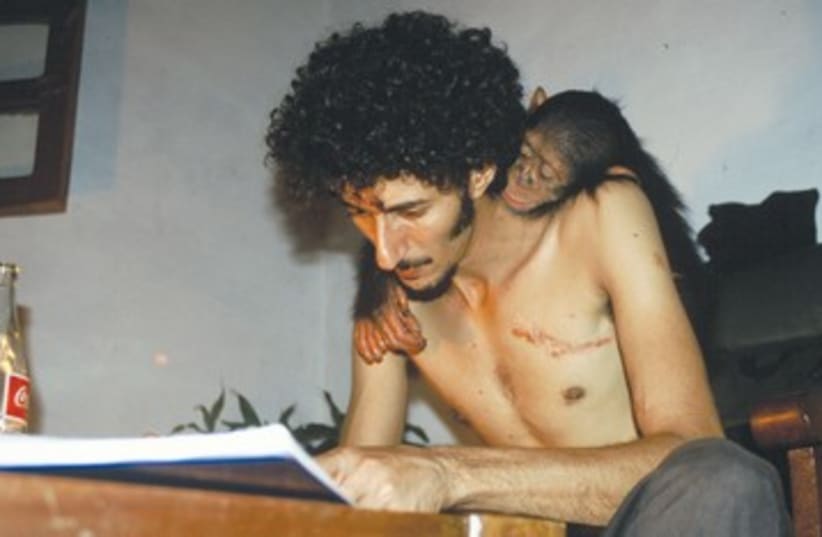

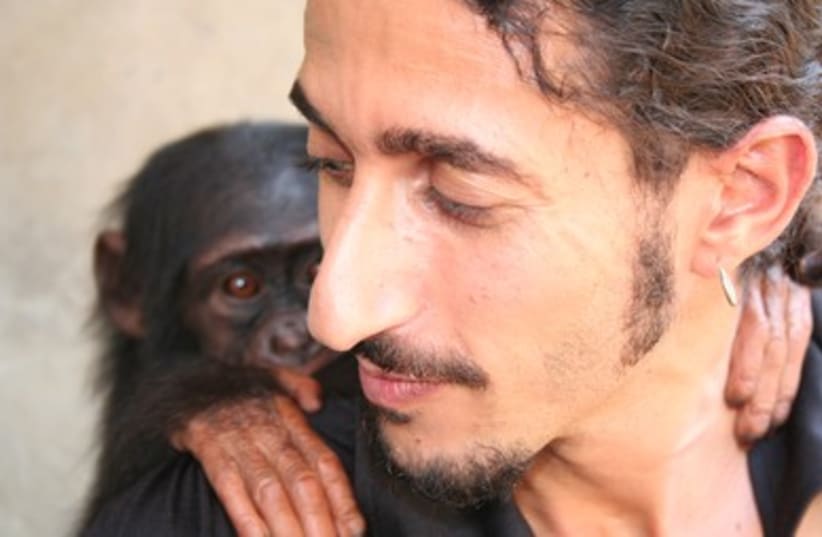

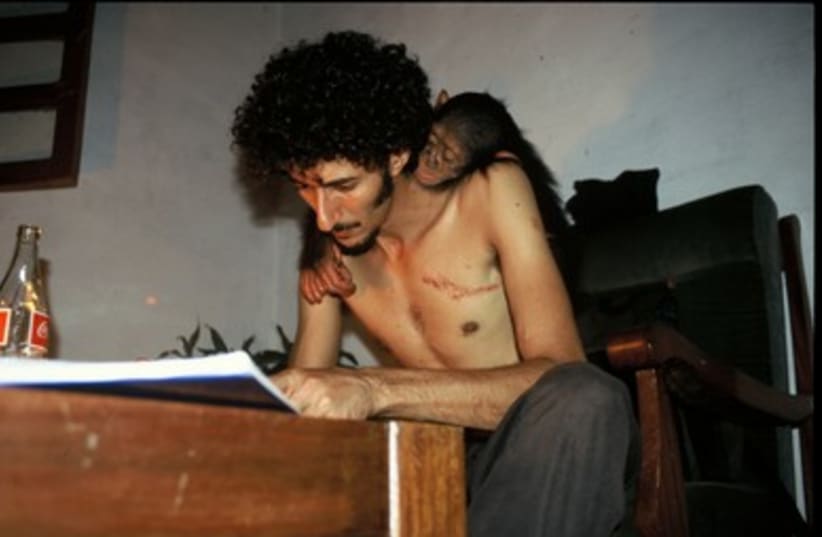

“I was walking thousands of kilometers, and that’s what I specialized in, finding the most remote places in Africa, where communities still retain their cultures and are apart from Western culture,” he told The Jerusalem Post on Sunday. “I had my share of adventures and misadventures.”Drori’s experiences snapping photographs in war zones and assisting in humanitarian operations turned him from an adventurer into an activist – a man “trying to give back to this continent that gave me so much.”Drori, now 36, will receive this year’s World Wildlife Fund for Nature Duke of Edinburgh Conservation Medal, which he will accept directly from the duke of Edinburgh, Prince Philip, and WWF international director Jim Leape, at Buckingham Palace on Monday evening.WWF has been awarding the Duke of Edinburgh Conservation Medal annually since 1970, honoring those have performed “outstanding service to the environment.”The organization selected Drori as this year’s winner for his work over the past decade as founder and director of both The Last Great Ape Organization Cameroon (LAGA) and the Central Africa Wildlife Law Enforcement Network – organizations that have led to hundreds of arrests and prosecutions of wildlife criminals.Drori, whom the WWF describes as a “tireless anti-corruption whistleblower,” has shifted Cameroon’s judicial system by curbing the organized wildlife trade that had escalated so sharply there in recent years, according to the awarding organization.“It is thanks to people like Ofir Drori that we still have a hope of keeping vulnerable elephants and other wildlife populations thriving – and keeping a spotlight on the poaching crisis that threatens them. I applaud his bold and impactful work,” Leape said. “WWF urges world governments to crack down on wildlife poaching and illegal trade as a matter of urgency.”While such hunting and trade has threatened gorillas, chimpanzees, elephants and other WWF flagship species, Drori’s efforts have “helped propagate a zero tolerance approach to illegal wildlife trafficking in Cameroon,” the WWF said.Amid Drori’s African journey, his intention upon arriving in Cameroon was to turn to apes and “take a break” from writing about human rights in Nigeria, for which he had received death threats, he explained.“It turned out that this break was becoming far longer than I thought and the extinction of apes was not such a simple story to write,” Drori said.A primary reason for ape endangerment, Drori discovered in 2003, was the complex network of organized crime behind the animal trafficking system, which involved powerful people and the cooperation of the police. Despite the fact that a law had been in place against such practices for nine years, Drori found himself asking the question – how often was this law being enforced? “The answer was shocking – the answer was a complete zero,” he said, noting that the same applied to almost all Western and Central African countries.After investigating the situation further, Drori said he also could not find any NGOs that focused on the enforcement either.“What I found were castles of these organizations and SUVs driving around everywhere but no answers,” he said. “It seemed that conservation was fueling corruption.”No article he could write or picture he could take as a photojournalist would be sufficient to capture the gravity of the situation, Drori decided.One morning, however, he said he left the capital city of Yaounde in Cameroon to explore the trade in a rural town known for distributing chimpanzee meat and gorilla hands.“The poachers were trying to sell me this baby chimp,” he said. “He was sick and abused, they were treating him like a rat.”When Drori went to the police, the officers simply requested bribes and even offered to sell him an additional baby chimpanzee, he explained.“That night I couldn’t sleep – I kept thinking of this baby chimp that would die soon,” he said.“The face of this baby chimp was just haunting me. I took all my anger against corruption on a piece of paper and started writing.”His writings turned into an outline for the NGO he was about to establish – LAGA – which would be a hands-on solution to enforcing the already existing laws, based on activism and passion, according to Drori.The next day, he returned to the dealers and informed them that by law, they could face three years of imprisonment.“They were totally unimpressed,” Drori said. “And that’s because they bribed their way out – the law doesn’t mean anything when it’s only in the book.”Drori then took a different tactic, fibbing that he was already part of a big, new international NGO that fights corruption and that a car was on its way to arrest the dealers.“This time the bluff was working – they got hysterical,” Drori said, noting that he was making fake phone calls to alleged NGO authorities. “I said, ‘Listen, if you will remain my informants and give me information to arrest bigger traffickers, I will see what I can do for you.’” Ultimately, the dealers cooperated and Drori took custody of the chimp, who quickly began hugging him.“I found myself as a father and a mother to a baby chimp,” he said. The chimp’s name would go on to be “Future,” and he stayed with Drori for a few months in a rented Cameroonian apartment, where he began his fight for the large apes.“This baby chimp made me do it,” he said.Although they had no seed funding, Drori and his new agents managed within seven months to bring about the firstever prosecution against animal trafficking for nearly all of Central and Western Africa. Since then, LAGA workers have been putting their own lives at risk to get a new major wildlife poacher or trafficker arrested approximately every week for the past seven years. In Cameroon alone, LAGA’s work has led to the arrest, prosecution and imprisonment of more than 450 criminals, he said.Out of LAGA grew the Central Africa Wildlife Law Enforcement Network, through which Drori and his team were able to export and replicate their system to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (the former Zaire), the Central African Republic, Gabon and Guinea. Three more countries will join this list by next year, according to Drori.Drori details all of these experiences in an April 2012 book he wrote with co-author David McDannald, called The Last Great Ape: A Journey through Africa and a Fight for the Heart of the Continent.In addition to LAGA and the Central Africa Wildlife Law Enforcement Network, Drori also established a humanitarian NGO called Anti Corruption in 2005.For Drori, receiving the WWF award at Buckingham Palace on Monday indicates “a certain recognition from the conservation establishment that there is a need to change. Conservation has to react to this wildlife trade crisis,” he said.The prize, he explained, demonstrates “a certain acceptance of our messages and our approach which is very different from mainstream conservation.”In 2007, Drori received the Clark Bavin Award for outstanding achievements in law enforcement, as well as the Interpol award for LAGA’s investigation, and the Golden Heart Award. He won 50,000 euros in 2011 from the Netherlandsbased Future for Nature Foundation, and in a few weeks, he will receive the $20,000 Conde Nast Traveler Environment Award in the United States.Thinking back about Future, the baby chimpanzee that thrust him into a career of activism, Drori said he has never visited his primate friend after the few months they lived together. Realizing that Future did not belong in a domesticated home, Drori brought him to a wildlife center that united him with an ape family and offered him rehabilitation. Soon, Future will leave that center and return to the wild.“There’s too much rejection looming,” Drori said. “I’m afraid to see him. He’s wild and I want him to be wild.”