Blood vessels can develop from lymphatic vessels according to a Weizmann Institute of Science peer-reviewed study published Wednesday in Nature.

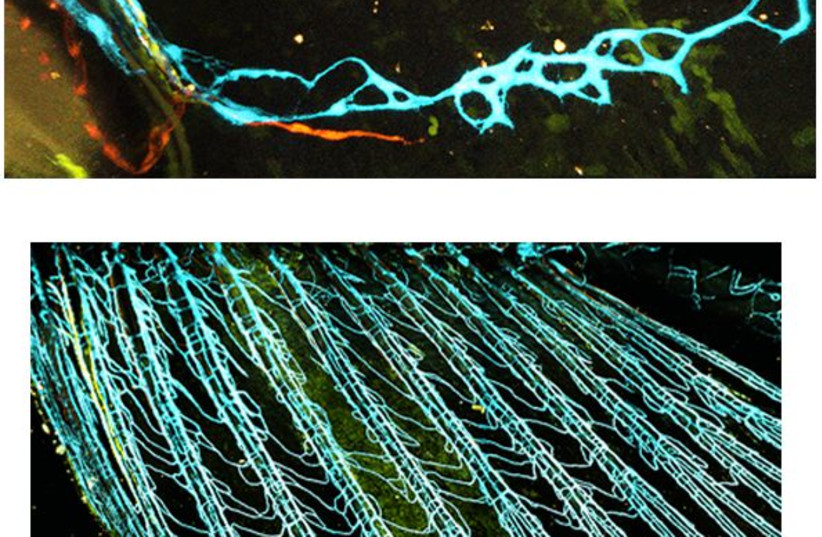

Until this point, new blood vessels were thought to develop either from other blood vessels or progenitor cells - descendants of stem cells. The discovery of this third source, lymphatic vessels, was revealed in genetically lab-altered zebrafish whose cells were labeled with fluorescent markers to enable tracing.

"It was known that blood vessels can give rise to lymphatic vessels, but we’ve shown for the first time that the reverse process can also take place in the course of normal development and growth,” explained Dr. Rudra N. Das, a postdoctoral fellow in Weizmann's Immunology and Regenerative Biology Department.

In examining juvenile zebrafish's fin growth, Das was able to discern that lymphatic vessels appeared before even the bones grew in. Some of these lymphatic vessels eventually lost their characteristic features and morphed into blood vessels.

Why hadn’t the blood vessels in the fins simply sprouted from a large nearby blood vessel?

The team analyzed mutant zebrafish that lacked lymphatic vessels and found that blood vessels in the fins did, in fact, branch off from existing blood vessels. However, the fins would grow abnormally, causing malformed bones and internal bleeding. Furthermore, excessive amounts of red blood cells - which carry oxygen - flooded into the newly-formed blood vessels. In the regular fish, the entry of red blood cells was controlled.

“We found that blood vessels must derive from the right source in order to function properly – it’s as if they remember where they came from,” said team leader Prof. Karina Yaniv.

The restricted presence of red blood cells evidently created low-oxygen conditions beneficial to proper bone development.

Is this relevant to human development?

The study’s findings are likely relevant to other vertebrates including humans.

“In past studies, whatever we discovered in fish was usually shown to be true for mammals as well.”

Prof. Karina Yaniv

These results could lead to new research in the study of human development. For example, they may help clarify the function of the specialized arrangement of blood vessels in the human placenta, which creates a low-oxygen environment for embryo development. The study's results could also lead to new discoveries in the realm of heart disease and cardiovascular health; heart attacks may be easier to treat if doctors better understand the specific features of the heart's coronary vessels.

Yaniv concluded: “On a more general level, we’ve demonstrated a link between the ‘biography’ of a blood vessel cell and its function in the adult organism. We’ve shown that a cell’s identity is shaped not only by its place of ‘residence,’ or the kinds of signals it receives from surrounding tissue, but also by the identity of its ‘parents.’”