The arrival of thousands of new immigrants and refugees from Ukraine and Russia in recent months – as well as predictions for tens of thousands in the near future – has alerted health authorities to the need to treat those infected with hepatitis C (HCV) before it develops into liver disease and cancer.

In Israel, there are some 880,000 people believed to be carriers and at risk of getting sick, including 26,004 who were added this year following the wave of immigration from Russia and Ukraine. The population at risk includes emigrants not only from the former Soviet Union but also from Romania, as well as organ transplant recipients, recipients of blood transfusions before 1992 and people who inject drugs.

World Hepatitis Day is marked every year on July 28th, the birthday of Nobel-prize-winning scientist Dr. Baruch Blumberg, who discovered the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and developed a diagnostic test and vaccine for it. With the encouragement of the World Health Organization (WHO), the day is celebrated to increase awareness of the hepatitis B and C viruses, to reduce new infections by 90% and to diagnose and treat those who were infected.

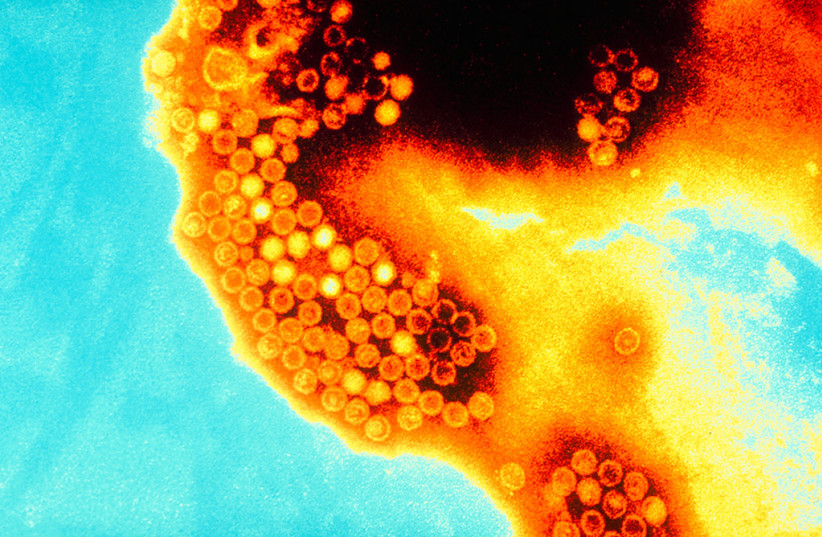

HCV is an infectious virus that primarily affects the liver. During the initial infection, people often have mild or even no symptoms. Occasionally a fever, dark urine, abdominal pain and yellow-tinged skin occur. Acute symptoms develop in some 20% to 30% of those infected about four to 12 weeks following infection. The virus persists in the liver in about 75% to 85% of those initially infected.

After many years, however, HCV often leads to liver disease and occasionally cirrhosis (scarring). In some cases, those with cirrhosis will develop serious complications such as liver failure, liver cancer or dilated blood vessels in the esophagus and stomach.

HCV is spread primarily by blood-to-blood contact associated with injection drug use, poorly sterilized medical equipment, needlestick injuries in healthcare and transfusions. Today, in Israel and other Western countries, blood donations are monitored and transfusions are not a source of infection, but in the former Soviet Union, a failure to properly oversee blood for transfusions and the reuse of poorly sterilized medical equipment there led to HCV infection in many residents.

Using blood screening, the risk from a transfusion is less than one per two million. It may also be spread from an infected mother to her baby during birth, but it is not spread by superficial contact.

Diagnosis is by blood testing to look for either antibodies to the virus or viral RNA. There is no vaccine against HCV, but prevention includes harm reduction efforts among people who inject drugs, testing donated blood and treatment of people with chronic infection, which can be cured more than 95% of the time with antiviral medications such as sofosbuvir or simeprevir.

An estimated 58 million people worldwide were infected with hepatitis C in 2019, and there were about 290,000 deaths, mainly from liver cancer and cirrhosis.

Dr. Yuval Dadon, director of the Health Ministry’s national program to eliminate HCV, said that, “by working together with the health funds, over 6,500 newcomers who were exposed to the virus were located and they are required to be further tested and treated accordingly.”

Preparation

In preparation for World Hepatitis Day, the directors-general of the four public health funds met with Dadon, along with the chief medical officers of the Israel Defense Forces, the Israel Prison Service, the Center for Local Government, the National Liver Council and the Israel Society for Liver Research.

Every year, many people are affected by various complications related to HCV carriers, the program director said. There are some 20 liver transplants, 75 cases of functional failure and 250 people who are diagnosed with cancer in an average year when almost all cases could have been prevented through diagnosis by a simple test and early treatment.

In recent years, despite the challenges of COVID-19, the Health Ministry has been able to locate the people required for HCV testing and set up a monitoring system for the implementation of the national plan to eradicate the virus. The WHO, which was a partner in launching the Israeli program, is working in cooperation with the ministry so that by the year 2030, the State of Israel will meet the goal set by the WHO to wipe out the virus.

The ministry told the four health funds that they must take a proactive approach regarding all their members in the high-risk groups, screen them for HCV and start treatment for all active carriers.

Liver cirrhosis can lead to portal hypertension, ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdomen), easy bruising or bleeding, enlarged veins – especially in the stomach and esophagus – jaundice and a syndrome of cognitive impairment known as hepatic encephalopathy.

It is believed that a minority of those infected are aware that they are HCV carriers. Routine screening for those between the ages of 18 and 79 was recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force in 2020. Before that, testing was recommended only for those at high risk, including injection drug users, those who had received blood transfusions before 1992, those who have been in prison, hemodialysis patients and people with tattoos.