More than a quarter of all stroke victims develop a strange disorder in which they they lose conscious awareness of half of all that their eyes see. After a stroke in the brain’s right half, for example, a person might eat only what's on the right side of the plate because they’re unaware of the other half or only the right half of a photo of themselves and ignore a person on their left side.

Surprisingly, such stroke victims can react emotionally to the entire photo or scene. Their brains seem to be taking it all in, but these people are consciously aware of only half the world.

Called unilateral neglect, this puzzling phenomenon highlights a longstanding question in brain science – what’s the difference between perceiving something and being aware or conscious of perceiving it? A person may not consciously note that he passed a shoe store while scrolling through his Instagram feed when her started searching online for shoe sales. The brain records things that one doesn’t consciously notice.

Where visual images are retained

Neuroscientists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU) and the University of California at Berkeley, now report that they may have found the region of the brain where these sustained visual images are retained during the few seconds that we perceive them. It has just been published in the journal Cell Reports under the title “Distinct ventral stream and prefrontal cortex representational dynamics during sustained conscious visual perception.”

The researchers recorded electrical activity in the brains of epilepsy patients while showing them various images in an attempt to find out where persistent images are stored in the brain and how we consciously access those images. “Consciousness – and in particular, visual experience – is the most fundamental thing that people feel from the moment they open their eyes when they wake up in the morning to the moment they go to sleep,” said Gal Vishne, a graduate student in the International Program for Computational Neuroscience at HU’s Safra Center for Brain Sciences and the lead author of the paper. “Our study is about your everyday experience.”

While the findings don’t yet explain how we can be unaware of what we see, studies like these could have practical applications in the future, allowing doctors to tell from a coma patient’s brain activity whether the person is still aware of the outside world and potentially able to improve. Understanding consciousness may also help doctors develop treatments for disorders of consciousness, she continued.

“The inspiration for my whole scientific career comes from patients with stroke who suffer from unilateral neglect,” added senior author and psychology Prof. Leon Deouell. “That actually triggered my whole interest in the question of conscious awareness. How is it that you can have the information but still not acknowledge it as something that you're subjectively experiencing, not act upon it, not move your eyes to it and not grab it? What is required for something not only to be sensed by the brain but for you to have a subjective experience? Understanding that would eventually help us understand what is missing in the cognitive system and in the brains of patients who have this kind of a syndrome.”

"We are adding a piece to the puzzle of consciousness – how things remain in your mind's eye for you to act on,” added UC Berkeley psychology Prof. Robert Knight, also a senior author and a member of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute.

Deouell noted that for some 60 years, electrical studies of the human brain have concentrated almost completely on the initial surge of activity after something is perceived, but this spike dies out after about 300 or 400 milliseconds, while we often look at and are consciously aware of things for seconds or longer. “That leaves a whole lot of time which is not explained in neural terms,” he said.

How did the scientists test their theory?

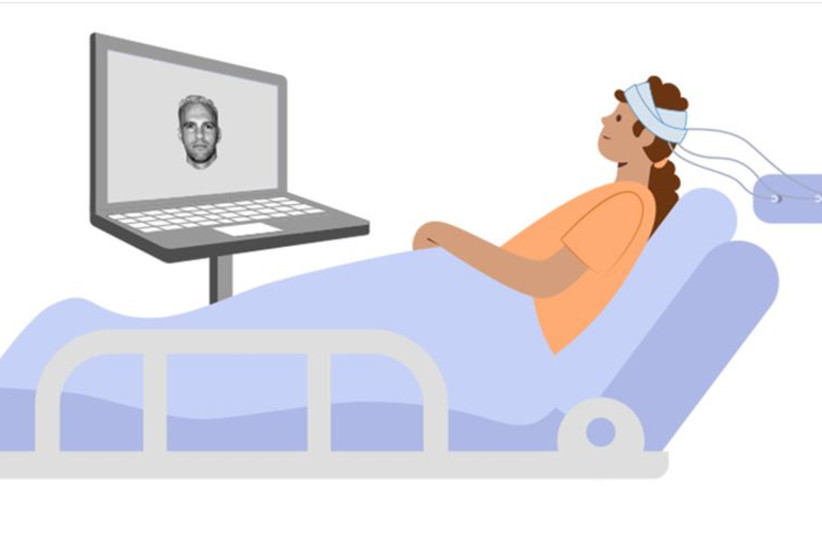

The neuroscientists received permission to run tests on 10 people whose skulls were being opened so that electrodes could be placed on the brain surface to track neural activity associated with epileptic seizures. The researchers recorded brain activity as they showed different images to the patients on a computer screen for different lengths of time, up to 1.5 seconds. The patients were asked to press a button when they saw an occasional item of clothing to ensure that they truly were paying attention.

Most methods used to record neural activity in humans like functional MRI (fMRI) or electroencephalography (EEG) allow researchers only to make detailed inferences about where brain activity is happening or when – but not both. By employing electrodes implanted inside the skull, researchers were able to bridge this gap.

After analyzing the data using machine learning, the team found that, contrary to earlier studies that saw only a brief burst of activity in the brain when something new was perceived, the visual areas of the brain actually retained information about the percept at a low level of activity for much longer. The sustained pattern of neural activity was similar to the pattern of the initial activity and changed when a person viewed a different image. “This stable representation suggests a neural basis for stable perception over time, despite the changing level of activity,” Deouell said.

The team’s findings have been confirmed by a group called the Cogitate Consortium; although the results are still awaiting peer review, they were described in a June event in New York that was billed as a face-off between two “leading” theories of consciousness. That adversarial collaboration involves two theories out of 22 current theories of consciousness,” Deouell cautioned. “Many theories usually means that we don't understand.” But the new study could lead to a true, testable theory of consciousness. Future studies will explore the electrical activity associated with consciousness in other regions of the brain including areas that deal with memory and emotions.