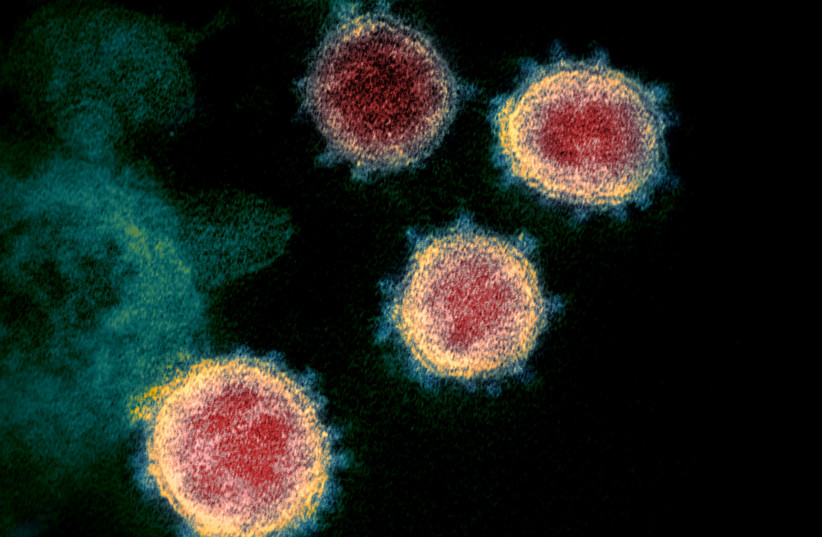

Immune particles within the blood of a llama may provide protection from every COVID-19 variant, as well as other viruses such as SARS-CoV-1, which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome, researchers at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York found in a new study.

The peer-reviewed study, published in Cell Reports on Tuesday, found that the immune particles, or nanobodies, could be used to develop an inhalable spray to combat COVID-19 and other viral diseases.

In comparison to other animals, llamas, alpacas and camels have two immune systems and produce antibodies with one peptide instead of two, according to Mount Sinai. These antibodies are about ten times smaller than normal ones, allowing them to be linked together to prevent mutant viruses from escaping.

“Because of their small size and broad neutralizing activities, these camelid nanobodies are likely to be effective against future variants and outbreaks of SARS-like viruses,” said lead study author Dr. Yi Shi, Associate Professor of Pharmacological Sciences and Director of the Center of Protein Engineering and Therapeutics at Mount Sinai's Icahn School of Medicine.

“Their superior stability, low production costs, and the ability to protect both the upper and lower respiratory tracts against infection mean they could provide a critical therapeutic to complement vaccines and monoclonal antibody drugs, if and when a new COVID-19 variant or SARS-CoV-3 emerges,” Shi said.

The study

“We learned that the tiny size of these nanobodies gives them a crucial advantage against a rapidly mutating virus.”

Ian Wilson, PhD, Hansen Professor of Structural Biology and Chair of the Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology, Scripps Research, La Jolla, California

The researchers immmunized a llama named Wally with the COVID-19 viral spike and found that repeating this process caused Wally to develop antibodies capable of fighting a wide range of viruses in addition to SARS-CoV-2, effectively granting the llama “super-immunity.” The researchers then isolated multiple antiviral nanobodies that are effective against many types of viruses.

“We learned that the tiny size of these nanobodies gives them a crucial advantage against a rapidly mutating virus,” said study co-author Dr. Ian Wilson, Hansen Professor of Structural Biology and Chair of the Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California.

“Specifically, it allows them to penetrate more of the recesses, nooks and crannies of the virus surface, and thus bind to multiple regions to prevent the virus from escaping and mutating,” he said.

Based on their findings, the researchers then created a powerful nanobody capable of binding to two regions on the spike of certain viruses in order to prevent them from mutating and subsequently escaping.