Out of all the sculptures on the frieze of the United States Supreme Court, the most immediately recognizable is Moses holding the Ten Commandments.

The connection between biblical law and modern secular justice systems has been thoroughly discussed, but neurologist Joel Y. Rutman wants to add another element to this discussion. In his book Moral Brain, Moral Bible, Rutman argues that the moral teachings of the Bible and biblical commentary actually reflect the inherent biological-based emotions and traits that evolved over the millennia before the Bible was written.

Rutman provocatively proposes that biblical laws don’t come from on high, rather, they come from inside us – from the evolution of our brains. With his short book, Rutman attempts to understand this biology and relate it to traditional, religious ways of thinking about moral behaviour. Or, as he phrases it in his introduction, “the book’s purpose is to show that Abraham’s moral sense and ours as well has roots in evolved human biology.” As such, he wants to ground the Bible in the brain.

It’s an intriguing idea, but unfortunately the book is underdeveloped. In his preface, Rutman admits he is “merely an armchair theorist without hands-on experience in many of the areas” he’ll be discussing, and that lack of expertise shows, not only in his insights but also his writing.

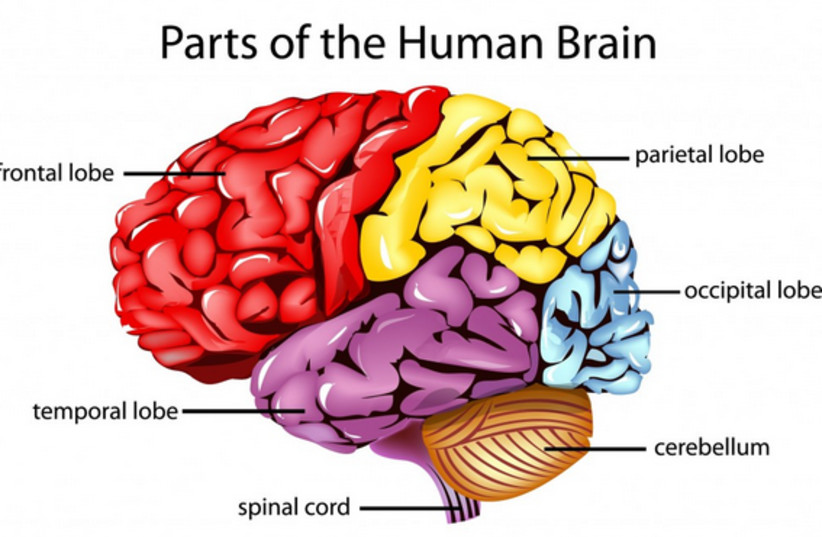

As a medical doctor, and a graduate of Brandeis and Harvard Medical School, Rutman clearly knows about the brain. But, his discussions of it and its accompanying diagrams are elementary to the point of being irrelevant, if not condescending. As he’s also a graduate of the Hebrew Academy and Yeshivath Adath in Cleveland, Ohio, I’m equally confident he knows his Bible, but he’s never able to convincingly present it as a document of moral instruction.

Part of the problem is a confusion of terms. Initially, Rutman clarifies that he’ll use the words moral and ethical interchangeably, because most people do. As a result, we’re never exactly sure what he means by moral behavior, especially because he spends too much of the book relating examples of hominoid and primate behavior, in an attempt to trace morality to behavior genetics.

He has chapters on empathy, altruism, and cooperation, but none of these make a case for morality. When discussing empathy, for example, he cites examples of mothers supporting their babies or strangers helping a child in need, but these are examples of compassion or pity, not empathy, which is a much more complex cognitive process. Empathy is, as Rutman clarifies, “the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing.”

For example, I can understand why someone who lives in a rural area and never sees anyone outside of their household might not want to get a COVID vaccination, even though I personally disagree with that choice. By using empathy, I eliminate judgment. But, Rutman and much of the Bible is talking about something else.

Another problem is Rutman’s lack of focus on the clearest moral teachings in the Bible, the Ten Commandments, or the moral teachings of other religions. Rutman notes that he won’t include in his discussion Buddhism or other non-biblical religions, for his lack of knowledge about them. But, in Buddhism, moral behavior is clearly defined in a negative sense. Right action or moral behavior is when someone refrains from taking life, taking what is not given, speaking falsely or committing sexual misconduct. The basic Buddhist precepts mirror the sixth, seventh, eight, and ninth commandments.

Yet Rutman doesn’t focus on these four commandments to make his case. Rather, he focuses on the biblical passages that encourage Jews to treat strangers fairly, which comes up 52 times, and to love your neighbor as yourself. But how to square these moral injunctions with the commandments of Leviticus 20:9-10, to put to death a child who speaks offensively to their parents or a woman who’s accused of adultery?

How to square the claim that the Bible encourages moral behavior with a god who commands Moses to slaughter 3,000 of his fellow Israelites after coming down from Mt. Sinai, in Exodus 32:28, not to mention exterminate all the people in the land of Canaan, in Deuteronomy 20:17? Even Abraham speaks falsely, David covets his neighbor’s wife and Solomon allows the worship of other gods.

No, the Bible is not a book of moral teachings, at least not in the way we currently think of morality – it’s much more than that, as it captures the complexity and ambiguity of human experience. And Rutman knows this—he acknowledges this counter argument. And so, wisely, he concludes with another approach: though our evolution has given us a moral inclination, which we can choose to ignore, biblical law forces us to aspire to holiness. It’s the force that’s important. Or as Rutman writes, “the act is key.”

To follow Jewish law, one must go against most of their baser and lazier inclinations, and be their better self. For example, Rutman writes, “When a friend or relative dies, empathy is not enough. We are expected to accompany the deceased for burial. It’s an ought.” In other words, in Judaism the deed creates the intention, not the other way around.

That is to say, evolution has only taken us so far – the Bible wants us to go further.

Moral Brain, Moral BibleBy Dr. Joel Y. RutmanValentine Mitchell146 pages; $22.95