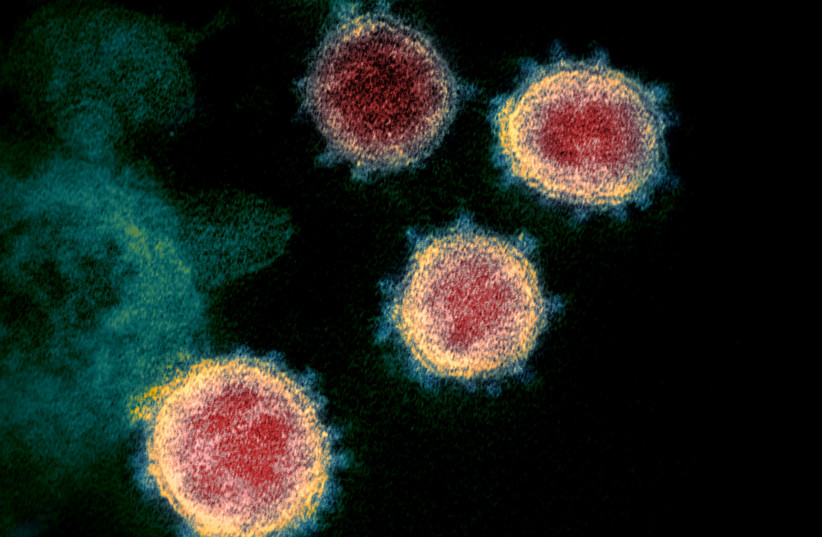

A new Northwestern University Medicine study published Friday shows that coronavirus vaccines and prior coronavirus infections can provide broad immunity against other, similar coronaviruses.

The findings were recently published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

The study found that plasma from humans who had been vaccinated against COVID-19 produced antibodies that were cross-reactive against SARS-CoV-1 and the “common cold” coronavirus (officially named HCoV-OC43), meaning they would potentially provide protection against several different kinds of coronaviruses.

The SARS-CoV-1 pandemic began in China in 2002, claiming the lives of 774 victims in total.

The study also found that prior coronavirus infections can protect against subsequent infections with other coronaviruses. For example, someone with immunity against SARS-CoV-1 would likely be protected against COVID-19.

Lastly, the scientists discovered several findings from their tests on mice. The mice immunized with a SARS-CoV-1 vaccine developed in 2004 generated immune responses that protected them from nasal exposure of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which caused the COVID-19 disease.

“As long as the coronavirus is greater than 70% related, the mice were protected,” researcher Pablo Penaloza-MacMaster said. “If they were exposed to a very different family of coronaviruses, the vaccines might confer less protection,” he added. This was seemingly confirmed by the immunized mice having much less protection against the “common cold” coronavirus.

The reason, the researchers explain, is because SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 are genetically similar, while the common cold coronavirus further contrasts from SARS-CoV-2.

“Our study helps us re-evaluate the concept of a universal coronavirus vaccine,” Penaloza-MacMaster states. “It’s likely there isn’t one, but we might end up with a generic vaccine for each of the main families of coronaviruses.”

Penaloza-MacMaster has studied HIV vaccines over the course of the last decade. His knowledge about HIV virus mutations led him to question cross-reactivity within coronavirus vaccines.

“A reason we don’t have an effective HIV vaccine is because it’s hard to develop cross-reactive antibodies, so we thought, ‘What if we tackle the problem of coronavirus variability (which is critical for developing universal coronavirus vaccines) the same way we’re tackling HIV vaccine development?’”

Researchers Tanushree Dangi and Nicole Palacio, both from Penaloza-MacMaster’s lab at Northwestern university, co-authored the study. Funding for the study was provided by the United States National Institutes of Health.