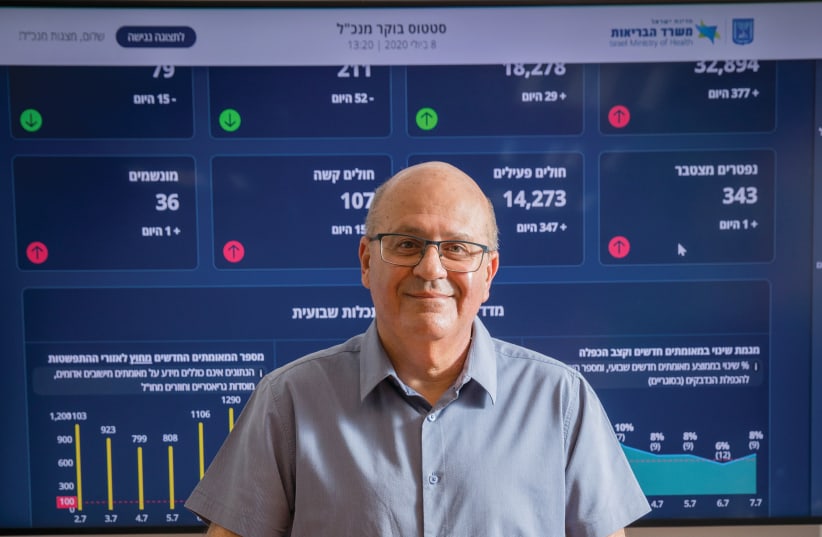

Speaking from his office on the fourth floor of the Health Ministry coronavirus headquarters in Airport City, Levy told the Magazine that Israel is correct to celebrate its “great achievement” of vaccinating more than 80% of its eligible population and upwards of 90% of people at high risk – a campaign the director-general modestly ran from behind the scenes.

But he also warned that it was too soon for Israel to let its guard down, especially at Ben-Gurion Airport, while the virus burns across the world at a rate of more than 670,000 new cases per day. In India alone, more than 330,000 people are being diagnosed with the virus each day and close to 3,000 dying.

Israel, on the other hand, is averaging less than 100 new daily cases and the death toll is in the single digits.

As he spoke Tuesday, a government decision was overdue on the Health Ministry’s request to block all non-essential travel for Israelis to and from countries with the highest levels of infection. The ministry was pressing to require 14 days of isolation for anyone entering Israel from one of these places, including green-passport holders who were vaccinated or recovered.

“We cannot say we have total herd immunity,” Levy explained. “We have 2.5 million kids who are not vaccinated, around 800,000 citizens that have still not vaccinated. We have gotten to a situation where the virus has reduced enough that we have totally opened up, gone back to our routines, opening the economy, the schools. It is impressive.

“The problem is the entrance to Israel through the airport and other passages,” Levy continued. “Look at Europe, Brazil, Ukraine, Turkey. India is a catastrophe that pulls at the strings of your heart. The airport can be the entry point for variants, even for those who are vaccinated, which is deadly dangerous.”

Levy said he is not opposed to opening the skies to allow some tourists to enter Israel. After all, it has been upwards of a year since the country let in any substantial number of visitors. But he said Israel cannot put itself in a situation where there is “no gatekeeper from the rest of the world,” especially when it is still unclear if the Pfizer vaccine on which the country has relied can hold up against certain variants.

He said every plane that arrived in Israel from India in the last two weeks was carrying sick people, despite them presenting a negative PCR test before boarding the aircraft.

Media reports said some of the infected travelers had been vaccinated, but Levy said this was false, though he did say it appears the vaccine could be less effective against the Indian variant than more traditional strains.

“We have to prevent the variants that could cause coronavirus to spread again,” he stressed. “We are really nervous that the opening of the skies could bring us back to where we started.”

The Health Ministry plan divides the world into two parts: those that are “safer” and those that are not. People traveling from highly infected countries would have a different set of rules. But Levy admitted that enforcement at Ben-Gurion has been ineffective at best during the crisis and “I am not sure” Israel can trust in it now.

“We don’t have a stable government, so anything can happen,” Levy said.

And there are, of course, still many unknowns, such as when Israelis will need a third shot to ensure their immunity to coronavirus does not wane.

The director-general said he believes the country’s next COVID-19 vaccination campaign will start at the beginning of 2022 with a re-engineered vaccine that will be more potent against variants.

Although Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has touted his close relationship with Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla, it was Levy’s signature on the first contract with the company for eight million doses that was signed on November 13, 2021 – before the vaccine was even approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The only other Israeli signature on the contract belonged to Health Ministry accountant Hassan Ismail.

“Today we finalized a critical supply agreement with the government of Israel that will provide the Israeli people with access to a COVID-19 vaccine once approved by regulatory authorities,” Bourla said that day.

The purchase of these vaccines was delayed due to government infighting, sparking concern among health officials like Levy that Israel may be bumped to the end of the vaccine line and not have the doses it needs to protect its citizens. The situation caused Levy to uncharacteristically lash out at the government during an interview, warning that political squabbling could endanger the country’s vaccination campaign.

“The State of Israel is engaged in a fierce struggle with the coronavirus that affects all aspects of everyday life of citizens of this state, in addition to other healthcare issues lurking on our threshold,” Levy said on the day he accepted the position. “I shall continue to lead the professional struggle against the coronavirus pandemic, and continue to do all in my power to ensure adequate and compassionate healthcare services in all areas for the benefit of Israel.”

A father of three and a grandfather of two granddaughters whose pictures he proudly displays on his office wall, Levy brought decades of experience to the position, including serving as the IDF’s chief medical officer.

A surgery specialist, Levy served in the First Lebanon War and subsequently headed the IDF’s humanitarian mission to Kosovo. He also participated in medical missions providing humanitarian assistance in Zaire, Kenya, Macedonia, Turkey and Rwanda.

He held previous roles in the Health Ministry, including senior deputy director-general, and most recently served as the director of Barzilai Hospital in Ashkelon, where he created its emergency room, underground hospital and fortified operation rooms. Under his authority, the hospital rose to third place in the country’s public satisfaction survey, leaping up from the bottom of the list.

As the pandemic unraveled – and the government alongside it – Levy became one of Israel’s only trusted voices on the pandemic. Almost nightly, he would address the nation through interviews on public television. No matter what he was asked, Levy would maintain his trademark calm and controlled demeanor.

His dimpled smile makes him feel more like a grandfather than a director-general, which likely helped relax the public.

He told the Magazine he stayed composed because he was “convinced that we were doing what was best.” He praised his top management team – Coronavirus Commissioner Prof. Nachman Ash and Head of Public Services Sharon Alroy-Preis – and said he consults with them and many other experts before making decisions.

“We argue a lot,” he said, “but we get to a decision that is balanced and professional.”

He said he sees it as his job to “take care of the people of Israel.... I am a physician, so it is easier for me [than the politicians] to be frank, to explain. The people deserve explanations.”

Though he has said he had a hard time dealing with the media, at least in the beginning.

“You learn to understand the power of things and the importance of every word and decision you make,” he said during the Eli Hurvitz Conference on Economy and Society in December. “The public has lost faith, but when you deal with the crisis, there are dilemmas: Not every dilemma is a misstep and not everything that is published was really said. The public has lost faith in the government... the public is not to blame.”Levy said sometimes he and his colleagues have felt unfairly targeted by pressures to fire them for no injustice committed on their part; their only offense was that “they represented their firm and professional truth.”

Recently, a group of protesters showed up in front of the Health Ministry, calling on Levy to retire or be blamed for the “murder” of all the country’s children by vaccination. They accused him of being a criminal.

“It’s not so easy,” he admitted.

ON THE TOPIC of vaccinating children, he said, “it is a complicated issue” and that Israel will not solely rely on the emergency approval of the vaccine for young people by the FDA or European Medical Association. Rather, he said, there are ongoing professional discussions among the Israeli medical community.

He mentioned the recent report that some young people who were inoculated developed inflammation of the heart, which can be deadly, and said, “We are only going to vaccinate our children when we are sure the vaccine is safe and efficient – mainly safe. When we are convinced, we can start.”

At the same time, he said Israel will not approve any vaccines that have not earned FDA or EMA recognition. Levy said that there was “a lot of pressure on us” to approve Russia’s Sputnik V, so much so that Israel sent a delegation to examine its production process. When health officials did not feel confident, “We didn’t buy it and didn’t vaccinate with it.”

The same, he said, will hold true for people coming into the country who have been inoculated with vaccines that Israel does not recognize. Their vaccinations will not be recognized and therefore they will be required to take a serological test that proves they have immunity before being granted a green pass. This could prove a diplomatic challenge since, for instance, most of Abu Dhabi was vaccinated with the Chinese vaccine.

“If we find they are not vaccinated, they will go into isolation,” Levy said. “If they are staying in Israel a long time, like some students, they will be able to get an Israeli vaccine. We have enough.”

He also said Israel has enough excess doses to vaccinate the Palestinians. Health officials had told the Magazine in the past that the plan was to inoculate the Palestinian population with Moderna.

Israel purchased some six million doses of the Moderna vaccine, most of which it has not yet been administered. Last week, it completed vaccinating 115,000 Palestinians who work in Israel. It has provided several thousand doses to the Palestinian Authority for its healthcare workers.

Levy said he is in regular contact with the Palestinian Health Ministry, and that health experts believe it is necessary to inoculate everyone living in the West Bank.

“But it is not just a health question,” Levy said. “It is an economic question, a political question, a question between governments. We [the health teams] can help them as much as we can.”

He noted that Israel has already assisted by receiving and transferring vaccines on behalf of the PA, and offering to store vaccines for them in the right conditions. When asked why 10 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine Israel paid for could not go to the Palestinians, Levy said the idea is not off the table.

“We have some scenarios for how to deal with it,” he said, without elaborating.

ASSUMING A GOVERNMENT is formed soon, it is unknown whether Levy will continue in his role. Director-general is a professional position but is appointed by the minister.

He stressed that the next director-general should be a physician, because “there are some heavy medical questions and I think it is not enough to have top physicians around you. I think you should know it, live it, breathe it.”

Prior to Levy taking his position, the role was held by Moshe Bar Siman Tov, who was the first non-doctor director-general of the ministry. He was in his position when the coronavirus crisis began and was largely responsible with Netanyahu for shutting down the airports and locking down the country, which helped Israel succeed in the first wave of the pandemic.

But he also was the one who told hospitals to cease elective and outpatient services, which some argue left people sicker and at risk of being diagnosed with acute diseases too late. He was also in office during Israel’s rapid reopening campaign in early May.

Levy said he is fortunate Edelstein selected him to take on this “really great challenge” and “to be in this role during a historical period, and work for the people of Israel.”

He said since being hired he has worked nonstop, from early in the morning until late at night, and sometimes he does not sleep because he is so concerned.

“I have gone all year with no life, no holiday, no weekends – nothing. You have to be everywhere, make every decision. There is no balance,” he said, though he said he does not regret joining the ministry.

“I am very happy to be in this position now,” he told the Magazine. “I look at it as holy and honorable work.”