With less than a year before Turks head to the polls to cast their votes in the upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections, Syrian refugees have become the focal point in the debate among the country’s political parties.

For more stories from The Media Line go to themedialine.org

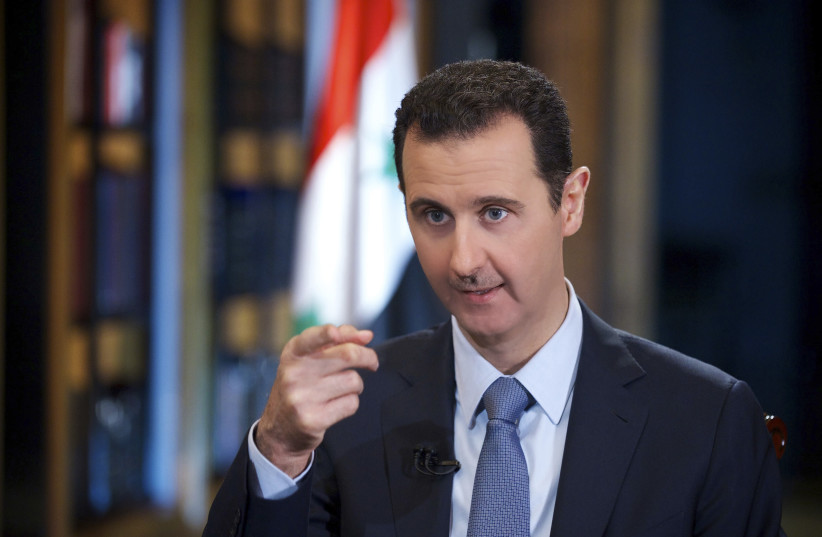

Last July, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan hinted at a possible rapprochement with Syrian President Bashar Assad, saying: “Political dialogue or diplomacy cannot be cut off between states.”

Erdoğan’s seeming shift in rhetoric was followed by his Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu’s statement to broadcaster Haber Global that Ankara would not set “conditions for dialogue” with Syria, but that any talks should focus on security on their border.

Ömer Özkizilcik, an analyst focusing on the Syrian crisis, the dynamics between rebel groups, and Middle Eastern security policy, told The Media Line that changing geopolitics may have played a role in the recent shift in Ankara’s position. He said the statements by the Turkish officials served two main purposes.

“The first one is to respond to the Russian pressure as now Russia has been pushing Turkey to speak with the Assad regime for a long time, and it appears that with Turkish mediation in Ukraine, Russia indicated that Turkey should also speak with the Assad regime.”

Calls inside Turkey to reestablish ties with Syria

“[Turkey] will say our goodbyes to our Syrian guests and will send them to their homes in two years.”

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, leader of the Republican People’s Party

The country’s president and its chief diplomat aren’t the only voices calling for reconciliation with Damascus.

For a decade, calls to send back Syrian refugees came from Turkey’s main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party, and its leader, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu.

To rally the masses around his party, Kılıçdaroğlu promised in July that if elected, Turkey “will say our goodbyes to our Syrian guests and will send them to their homes in two years.”

According to the United Nations, Turkey has been a haven for nearly 3.7 million Syrian refugees.

But Ankara’s softening tone against Assad leaves many of the refugees worried as the number of verbal and physical attacks against them is on the rise and many attribute this to calls by the Turkish opposition to deport them, claiming that the country’s economic and financial woes are a result of hosting the Syrians.

Turkey has been a staunch enemy of Assad and one of the main supporters of the Syrian opposition and armed factions that have fought to oust the Syrian leader.

In the civil war’s early days, Erdoğan described Assad as a “terrorist” and one who would “pay the price” for the Syrian lives lost in the war.

Conciliatory statements by Turkish officials are, however, a calculated move directed at a domestic audience ahead of next year’s elections.

Özkizilcik says that’s where the second and more “important aspect” of these statements comes in.

“They have a domestic and political purpose. In Turkey there are two main issues before the elections: The first one is economic and the second is migration,” he says. “The Turkish opposition has been arguing for years now that Syrian refugees are in Turkey because of the stubbornness of the Turkish government.”

He says it’s more of a political ploy and maneuver by Erdoğan and his government to give him an edge over the opposition, so as not to be upstaged by them. Because the president is facing a low popularity rate and stiff opposition 10 months before the election, he seems to be appeasing his base with his statement.

Özkizilcik says the Turkish government has for years tried to argue that it’s not as easy as claimed by the Turkish opposition.

“Unfortunately, the public debate has been run by the Turkish opposition, as they stated that making peace efforts with the regime will insure the celebratory return of millions of refugees to Syria.”

Hostility between the two governments began over a decade ago but many observers question the sincerity of the Turkish side in kissing and making up with the Syrian government.

“In politics, everything is possible,” Dr. Ammar Kahf, executive director of the Istanbul-based Omran Center for Strategic Studies and a member of the board of the Syrian Forum consortium of nonprofit organizations, told The Media Line.

Kahf is skeptical that these statements signal a renewal of diplomatic ties.

“Politics in the post Arab Spring and post 9/11 [eras] has changed to become much more fragmented and transactional. So, when countries speak of reconciliation or animosity, no country means [what it says] in absolute terms.”

To say that there’s no communication between the two governments is inaccurate, as intelligence officials from both sides share information on terrorism, and low-level officials have met sporadically.

“Communication on intelligence will continue because it’s necessary, but on the diplomatic front there will be no progress,” says Özkizilcik.

He argues that even if Turkey is willing to reconcile, Damascus won’t be interested in a step like this.

“I don’t think that the Assad regime would be willing to make just a political gesture toward the Turkish president, especially 10 months ahead of the elections,” Özkizilcik explains.

But with the mediation role Erdoğan is playing between Moscow and Kyiv, and Russia’s deep involvement in Syria, Kahf says Ankara has no choice but to look flexible.

“The Turkish-Syrian paradigm has shifted since the involvement of Russia in 2015, so the priorities of Turkey have been shuffled several times,” says Kahf.

He accuses Washington of strengthening Assad’s rule for the purpose of getting rid of the Islamic State group.

“The American involvement has to be blamed for empowering the Assad regime both militarily and politically in the region.”

Do Turkish officials think it is conceivable that Ankara and Damascus will patch up their differences? Kahf’s answer is no.

“I don’t see it as a purely tactical move meant for domestic consumption. It’s mostly directed at the Russian leadership and a smaller part of it at the local audience – to take the refugee card out of the hands of the opposition,” says Kahf.