Four weeks have passed since the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague issued provisional measures against Israel for alleged acts of genocide, as argued by South Africa in court. Israel has less than a week to report to the ICJ on its response to the court’s order.

For more stories from The Media Line go to themedialine.org

Reactions to the court’s ruling have been sharply divided. Some legal experts praise the verdict as a first step toward justice, potentially leading to future charges against Israel’s arms and funding sources, including the United States.

Tahseen Elayyan, a legal researcher for Al-Haq, a Palestinian human rights NGO in Ramallah, West Bank, tells The Media Line that the court’s decision is satisfactory, as it provided “faith in the intranational [sic] legal and justice system … at a time when Palestinians in general and human rights defenders in particular have become very frustrated from the system considering the double-standards policy and politicization of justice by Western states and accountability mechanisms and jurisdictions.”

Elayyan also argues that by ordering the provisional measures, the court may not have directly ordered a cease-fire, but “enforcing the provisional measures requires a cease-fire in practice.”

Others, like Thomas Warrick, an international law expert and former deputy assistant secretary for counterterrorism policy at the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), now director of the Future of DHS Project at the Snowcroft Center for Strategy and Security’s Forward Defense, are confident South Africa will not provide enough evidence for its charges.

In a statement to the Atlantic Council, Warrick describes the court’s request for a report from Israel as “an opportunity, not a sanction, to present more evidence, like recently declassified cabinet minutes, to explain the intent behind Israel’s campaign to remove Hamas from power in Gaza.”

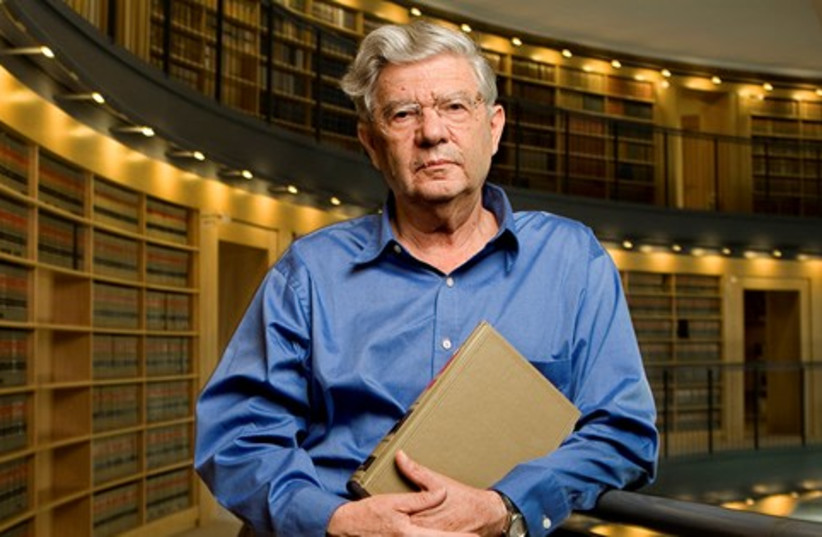

Irit Kohn, president of the International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists and former director of the International Affairs Department at Israel’s Justice Ministry, expresses skepticism about the case’s objectivity.

“Israel has already adjusted to the idea that everything we are doing, whether right or wrong, will result in our being tried,” she says. “And why am I saying it? Because if you look at other disputes in the world—take Syria, take Ukraine, [and] the many disputes between Muslims that are killing each other—and they never brought it to the court.”

Kohn is distressed by South Africa’s presentation, claiming, “The things South Africa’s lawyers said about Israel were more than half lies.” She recalls a time in Geneva, as president of the International Association of Jewish Lawyers, when “someone got up and said the Israeli army is killing Arabs and taking their body parts to transplant them to the bodies of Israelis.” Such claims have been repeatedly levied against Israel—so far without evidence of any systemic abuse whatsoever.

Elayyan contends the narrative is reversed, stating “Israel and the West want the Palestinians to act as good victims.” When Palestinians resist being “killed, tortured, dehumanized, and kept silent,” they are labeled terrorists, he says.

“We must not ignore the context which pushed [the] Palestinian resistance,” Elayyan says, referring to Hamas, an acronym that means “the resistance” in Arabic. “The events of October 7 are a response to Israeli policies of subjugation, fragmentation, control, and colonization,” he adds.

Whether Hamas’ atrocities on October 7—in which the terror group kidnapped over 250 people and murdered, mutilated, and in some cases raped more than 1200 mostly civilian men, women, and children—are considered legitimate “resistance” is a matter of perspective.

The Court’s Findings

The ICJ, without making preliminary judgments, believes South Africa’s allegations have enough merit to warrant a trial, a process that could span years.

Broadly speaking, and without making any judgments, the ICJ believes South Africa’s allegations have enough merit to warrant a trial, a process that could span years.

For this reason, and in light of the time-sensitive nature of the matter, the court sternly called on Israel to adhere to the rules of the genocide convention—to which Israel is already a party—by preventing or punishing violations of the genocide convention, facilitating the supply of aid to Gaza, preserving evidence for potential investigations in the future, and reporting on measures to do so.

This interim ruling diverges significantly from the Israeli defense team’s plea to dismiss the case, arguing South Africa failed to prove its claims or establish jurisdiction. However, neither did the court demand that Israel cease its campaign against Hamas, as well as all other military activities in Gaza, as South Africa called for.

This decision itself seemingly reflects the differences of opinion among the court.

Fifteen out of 17 judges supported all provisional measures. ICJ Vice President Julia Sebutinde from Uganda and Judge ad hoc Aharon Barak, the temporary appointee from Israel, were the only dissenting voices.

Judge Barak opposed four of the court’s six measures, concurring only with the need for Israel to facilitate humanitarian aid to Gaza and to prevent and punish any incitement to commit genocide.

In his detailed 10-page dissent, Barak criticizes the court for overlooking Hamas’ involvement and ongoing war crimes, as well as Israel’s right and duty to defend against Hamas, a group intent on Israel’s destruction.

Additionally, as “the other belligerent in the armed conflict in Gaza, Hamas is not a party to the present proceedings … it is not possible to indicate measures directed at Hamas in the order’s operative clause” and “it is an essential matter to be considered when determining the appropriate measures or remedies in this case.”

Barak also questions South Africa’s sincerity in bringing this dispute to the court, suggesting a lack of good faith.

“After South Africa sent a note verbale to Israel on 21 December 2023, concerning the situation in Gaza,” Barak writes, “Israel replied with an offer to engage in consultations at the earliest possible opportunity. Instead of accepting this offer, South Africa, which could have led to fruitful diplomatic talks, decided to institute proceedings against Israel before this court. Regrettably, Israel’s attempt to open a dialogue was met with filing an application.”

Kohn also probes the “good faith” of South Africa’s actions, suggesting political motives underpin the decision to take legal action.

“I don’t know if it’s right or wrong,” Kohn says before going into detail about repeated if unproven allegations from various human rights organizations and news outlets that South Africa’s leading ANC party was facing bankruptcy until Iran and its allies offered to bail them out … for a price.

Most powerfully, though, Barak shares his background as a Holocaust survivor from Lithuania, reflecting on how this shapes his views on genocide and Israel’s military ethics.

“Israel is a democracy with a strong legal system and an independent judicial system,” writes Barak, adding that where there is conflict between national security and human rights, the former must be attained without compromising the latter’s protection.

Barak provides an example: “Once, in the midst of a military operation in Gaza, the Supreme Court ordered the army to repair the water pipes that had been damaged by army tanks and to do so while the operation was still ongoing. On the same occasion, it ordered the army to provide humanitarian aid to civilians and to halt hostilities to allow for the burial of the dead.”

Judge Sebutinde opposed all the measures, arguing they were unjustified, especially since they mostly demanded Israel comply with the Genocide Convention obligations, to which it is already committed, making the court’s directives seem redundant.

In her dissenting opinion, Sebutinde states, “The dispute between the State of Israel and the people of Palestine is essentially and historically a political one, calling for a diplomatic or negotiated settlement, and for the implementation in good faith of all relevant Security Council resolutions by all parties concerned, with a view to finding a permanent solution whereby the Israeli and Palestinian peoples can peacefully coexist.”

She further notes South Africa did not fulfill the Genocide Convention’s criteria, prove the court’s jurisdiction, or show, even preliminarily, that Israel’s alleged actions were carried out with genocidal intent.

Elayyan wholly rejects Sebutinde’s and Barak’s findings. “He [Barak] is biased. He was part of the so-called Israeli High Court of Justice, which, in many instances, justified the crimes committed by Israeli occupying authorities against Palestinians and their properties. No surprise that he took this position in this case.”

Regarding Sebutinde’s point of intent, Elayyan says Israel’s actions speak louder than words. “Even if we assume that Israeli claims [against Hamas’ use of human shields and of embedding militants among civilians and civilian infrastructure] are true, Israel must respect the principle of proportionality in the conduct of hostilities. The number of harm and casualties among civilians shows that there is an intention to cause this level of suffering.

Elayyan also accuses Israel of committing genocide through forced displacement, irrespective of Gazans’ ability to rebuild after the war. “This crime is not subject to statutory limitations. It has already been started and is still being committed. Perpetrators must be held accountable. Also, survivors are entitled to reparations.”

Responding to Sebutinde’s view that the conflict is political, Elayyan says, “Palestinians have tried ‘peace talks’ for 30 years” without result and “at the end of the day, peace cannot be achieved without justice.”

Conversely, Kohn takes an opposing view, praising Barak’s minority opinion, filled with case studies and legal precedents. “It should be studied in history books,” she says.

Kohn also commends Sebutinde’s courage in her ruling, especially given the political pressures from her home country, Uganda.

The Politics

Indeed, reactions to the case appear influenced by political or group affiliations. A poll by the Israel Democracy Institute showed varied perceptions on the ICJ’s stance towards Israel: 50% of Jewish Israelis found it harsh, 39% lenient, and 11% were unsure. Among Arab Israelis, 19% saw it as harsh, 46% as lenient, and 35% were undecided.

Similarly, opinions diverged along political lines: 60% of the Israeli right deemed the ruling harsh, while 65% of the left considered it lenient.

Kohn suggests that the United States’ support or criticism of Israel should be interpreted through a political lens.

Responding to reports of the Biden Administration conditioning US military aid on Israel providing “credible assurances” of adherence to international law, Kohn expresses profound gratitude toward President Biden for understanding Israel’s long standing struggles with Hamas: “I don’t have enough words to thank him,” she says.

“But let’s try to be objective,” she continues. “It’s close to election day in the United States, and he has to satisfy all kinds of different bodies in the state.” Nonetheless, Kohn believes Israel should easily manage to produce the requested report.

“The army has a very, very good legal department, which constantly refreshes the minds of the soldiers and officers about what has to be done and what has not to be done. So when the court orders a report within a month, we say it won’t be a problem,” Kohn asserts, noting such documentation is routine.