The natural reaction would have been to recoil, from the sheer brutality of the Hamas attacks on Israel almost one year ago and the now widening war that it spawned.

“That’s exactly what the haters want to happen, for us to become insular, fearful, paranoid,” said Rabbi Daniel Burg of Beth Am in Baltimore’s Reservoir Hill neighborhood. “We’re none of that.”

In the year since the Oct. 7 attacks, he is among those in Baltimore’s Jewish and Muslim communities who have been living with the horrors of a conflict that may be at great physical distance yet hits particularly close to home and heart.

“Is there any healing in this?” Imam Earl El-Amin of the Muslim Community Cultural Center in West Baltimore mused aloud. “The only answer is love and reconciliation so that people can coexist together in peace.”

Some will gather to mark the sad anniversary. On Monday, Beth El Congregation in Pikesville will host a program, which has sold out, featuring Oct. 7 survivors and families of victims, prayers and other reflections.

For many, the day is neither the beginning nor the end of their attempt to process the war — both within their own circles, and crossing the divides that otherwise might separate them. Many have family and friends in the besieged region that they have visited, all feel connected by their faith and culture.

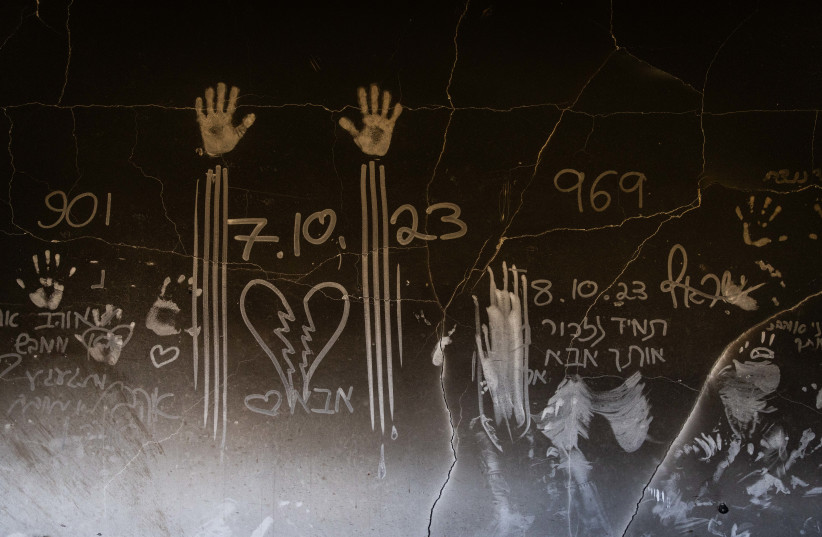

In images from half a world away, they see themselves and their loved ones: In the young revelers at a music festival in the Israeli desert, among the sites stormed by Hamas terrorists on Oct. 7 in a killing, kidnapping and raping frenzy. In the children, so many children, in Gaza killed in Israeli bombings or by starvation or lack of health care.

“It’s no longer possible to shelter kids from the realities of the world,” said Saad Baig, head of the Islamic Society of Baltimore’s Al-Rahwah School in Woodlawn. “These days, kids are walking around with phones, and they are directly exposed to images of death and destruction through social media platforms.”

Seeing “images of children their own age, who look just like them or their classmates, being maimed and killed,” has left them heartbroken, but determined and even hopeful, said Baig, also the ISB’s resident scholar.

“Their empathy and willingness to take action have been inspiring,” he said. Even the pre-K students have tried to help, Baig said, having a smoothie sale to raise funds for school supplies for children in Gaza.

Several weeks after Oct. 7, Burg traveled to Israel. He donated blood, but mostly he bore witness. In a Kevlar helmet and flak jacket, he went to Kibbutz Be’eri, among the hardest hit in the Oct. 7 attacks with 101 civilians killed and 30 kidnapped.

“There were still bloody knives, the remnants of burnt bodies, blood. They’d removed everything they could, but … it was pretty horrific, very hard to see,” he said. “I knew then that this was going to be a long war, and that made me very sad.”

Back home, his congregants will carry cards, each with the name of someone killed on Oct. 7, to their seats for Yom Kippur services next weekend. He remains committed to engaging “beyond our walls” and into the larger Baltimore community. And in fact, the synagogue hosted one of the events organized by a group, Voices of Peace, that brought Jews and Muslims together this year in a nonpolitical, nonjudgmental way about the conflict.

The group was started by two friends: Sumayyah Bilal, who is Muslim and owns the Codetta Bake Shop in Federal Hill, and Rebekka Paisner, who is Jewish and a Hopkins Ph.D. student. They turned immediately to one another in the aftermath of Oct. 7 as they tried to sort through their emotions. They began organizing gatherings, which continue on occasion, for others to similarly address the fraught topic.

“There are times when I feel very powerless and small,” Bilal said. “What I can do is make connections and make our corner of the world brighter.”

Paisner said some might want the Voices of Peace discussions to be more political, but a ground rule is that nothing said is meant to draw a reaction, pro or con, but instead to “deeply” listen to one another.

“We are open to hear your pain so we can all move through this together,” she said.

Elsewhere, there has been less unity.

In November, Hopkins put on leave a physician on its medical school faculty who had called Palestinians “animals” and seemingly endorsed “large-scale slaughter.”

That same month, the Maryland Commission on Hate Crime Response and Prevention also became embroiled in the tensions, with the suspension of member Zainab Chaudry, the director of the state chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, over Facebook posts viewed by some as antisemitic. Then, the resignation of her successor, Ayman Nassar, was accepted after allegations that he was pro-Hamas.

The war roiled colleges across the country, including Hopkins, during the last academic year, with encampments of pro-Palestinian protesters sprouting on campuses including Johns Hopkins. The tent city on the Homewood campus’ “Beach” came down last spring after Hopkins agreed to conduct a review of the protestors’ demands for divesting from companies supporting Israel by June 2025.

A Hopkins spokesman said the university is “engaging with students to support them in finding safe and successful avenues for expression.” The school sent students a letter recently noting that reports of antisemitism and Islamophobia on college campuses including Hopkins have been on the rise in recent years, and no religious harassment or discrimination would be tolerated.

Students for Justice in Palestine will hold a vigil at the University of Maryland College Park, having won its case in federal court last week against the university, which, facing public pressure and citing safety concerns, had previously disallowed the event.

Other campuses have wrestled with issues of free speech and safety over the more charged protests, which have been threatening to some Jewish students.

Rabbi Mitchell Wohlberg, who for more that 43 years led Beth Tfiloh Congregation in Pikesville, the largest Modern Orthodox congregation in North America, said he is saddened by what he views as the loss of multiple former allies of Jews and Israel.

“I’m talking about the African-American community, the gay community, the academic community. I can keep going,” Wohlberg said. “All of the causes that we supported with a full heart — we were there for them… They’ve all swallowed the whole progressive white-Black, colonial-suppressed shtick.”

Within the Jewish community, there is a range of views. Rabbi Ariana Katz, the founding rabbi of Hinenu: the Baltimore Justice Shtiebl, a left-leaning synagogue and community, has participated in pro-Palestinian and pro-ceasefire demonstrations and accuses the Israeli government of perpetrating “a genocide.”

“Acting to save life is the highest Jewish value. For me, solidarity with the movement — participating in the movement for ceasefire, for justice for Palestinians — that stems from my Jewish values, because I know it guarantees safety for Jews and for Palestinians,” she said.

As the one-year mark approaches, many in Baltimore are watching anxiously as the war widens to encompass Lebanon and Iran.

“It’s painful what we’re witnessing,” said Sharif Silmi, a lawyer who lives in Catonsville and is active with both the ISB and CAIR. “We don’t need another war.”

Silmi, whose Palestinian family members first came to the U.S. in 1918, takes a long view, saying today’s conflict cannot be understood without the context of the decades of struggle that preceded it. He takes heart, though, that young people he’s met, particularly on college campuses, who he said have sought to learn more about his people’s plight.

Bridging the gap

The shock of the Oct. 7 attacks and the subsequent war has been challenging to those who seek to bridge religious and other divides, said Imam Mohamad Bashar Arafat, whose Columbia-based Civilizations Exchange and Cooperation Foundation offers a range of programs to do just that.

“For the first few months, It was very tough,” said Arafat, a former Muslim chaplain for Hopkins and the Baltimore City Police Department. “People were not ready to hear anything,”

Now though, it’s “completely different,” he said, as more people seek to understand the backdrop of a war going into its second year. He thinks of how his wife, was recently at a Walmart, where a woman approached and asked about some things — misconceptions, Arafat said — she’d heard about Muslims. They talked so long, Arafat said, the woman’s husband started honking the horn of his car in the parking lot.

“Our biggest enemy is ignorance,” he said, “and misinformation about the other.”

Ultimately, Arafat said, the only solution for the “tit for tat” cycle of violence is for people to take the initiative to reach across what divides them.

“I don’t know how we are going to go forward if we don’t address how we are going to live side by side,” he said. “We have no other alternative but to work for peace because we can’t fight forever.”