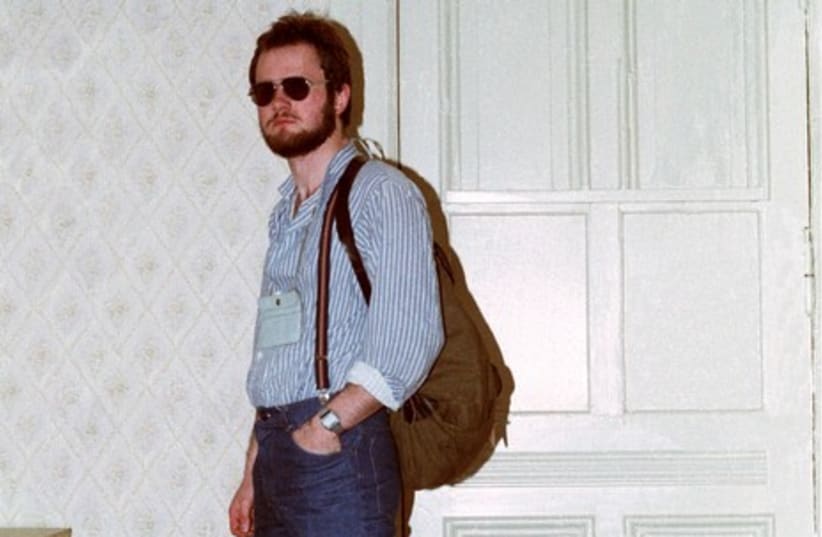

German artist Simon Menner, who put together the exhibition "Pictures from the Secret Stasi Archives," said it should show how something that seems harmless, such as these images that could be shots from a spy film spoof, can harbor danger.RELATED:Israeli history photo of the week: King David lives onPhoto Critique: Telling a story"These were used during courses on how to dress up and blend into society," the 33 year-old artist said. "They seem pretty absurd now, but it was meant seriously -- this is evil stuff."Menner says he aims to fuel a debate about the problems inherent to the concept of surveillance, using evidence of the way the Stasi secret police functioned in the Cold War."These are once highly classified images taken by a secret service that were never meant to be published -- just imagine this was an exhibition of photographs from the CIA!," he said."Here in Germany we have this treasure, an archive that is pretty much open to everyone -- something worth so much, especially in a time when we are debating surveillance issues."

Germany has some of the toughest privacy laws in the world due to its experience with state surveillance systems once used by the Nazis and the Stasi.Menner spent days combing through the vast archives once built by the Stasi using a network of informants numbering one in 90 East German citizens and open to the public since 1990.In one row of images, a spy exhibits disguises, from the Russian mafioso wearing a furry hat and trenchcoat to the casual middle-aged man sporting a cardigan and buttoned-up shirt.Menner also uncovered Polaroid photos made by Stasi agents when they secretly searched peoples' houses on the hunt for evidence they might be betraying the communist state."The people who lived there were never informed when their flats were searched, so the first thing the agents did was to take Polaroid images of the apartment to be able afterwards to put everything back in its original position," he said.These photographs seem harmless at first, showing an unmade bed, a sprawl of shoes, papers on a desk. Yet they testify to the insidious invasion of the Stasi into peoples' private lives.They also underline a universal problem with secret services and preemptive surveillance, says Menner: ordinary people naturally prone to misperception are enshrined with great powers and left free to interpret evidence as they wish.A West German coffee maker could be seen as proof by the Stasi that someone was a spy, or simply proof they liked coffee."Depending on which interpretation you choose, the coffee-maker owner could end up on jail," said Menner, who has frequently explored the idea of an Orwellian Big Brother in his own photographic oeuvre."But that is not something that can actually be found in the image but rather decided by some Big Brother...you see through these images some of the general problems with surveillance."The problem of misperceptions arising from surveillance was not just a relic of the Cold War, and could be found in western society too, with potentially fatal consequences, Menner said.Menner referred to a video leaked last year which showed how a U.S. helicopter crew in Iraq mistook a camera for a rocket-propelled grenade launcher and killed the cameraman."The idea of a common enemy brings society together," he said. "Maybe surveillance does make western society more secure but we have to be very careful with it."Some of the more surprising images in the exhibition show the spies of the western Allied Forces photographing the Stasi spies, sometimes laughing at the absurdity of the situation.Menner explained that among the allied powers, there were small units allowed to move freely between East and West Germany, with each side considering these "military liaison missions" as an ideal opportunity for spying."Sometimes they met, both sides were absolutely aware that the other side was there, but nevertheless both sides took photos, showing that both East and West lived in pretty much the same state of mind," he said, noting that he was unable to obtain the counterpart images from the British or Federal German secret services."The Cold War is over...and yet there is still no way for me to get hold of these images," said Menner. "This again shows just how valuable these pictures are."