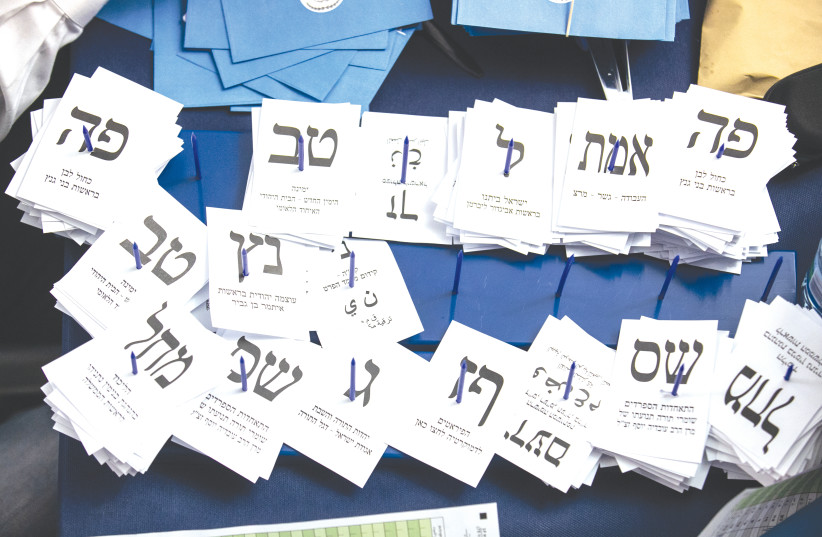

Israel is heading to the polls. Again. Come November 1, Israelis vote in their fifth general election in just over three and a half years.

For more stories from The Media Line go to themedialine.org

The most recent election, held in March 2021, followed closely after three ones that only fortified the political impasse, rather than solving it, with transitional governments all the while. After those back-to-back campaigns, an unlikely coalition was finally formed, composed of eight parties from all over the political spectrum. It gave the country a break.

On June 20, when then-prime minister Naftali Bennett announced he would call for a vote to dissolve the parliament, there was renewed concern that citizens were feeling let down by the system and the politicians. That this time around, they might voice their discontent by not showing up on Election Day.

Voter turnout is considered the main indicator of voter fatigue, the only one that can be accurately measured. However, with such a heterogeneous society, voter turnout in Israel is subject to many influencing factors and does not necessarily accurately reflect whether voters are fed up with the political system. The turnout also varies greatly within the different sectors of society.

When the political crisis began with the first of the five elections, in April 2019, voter turnout was almost 68%. According to data released by the Central Elections Committee, it increased in the following two rounds in September 2019 and March 2020, peaking in the latter at 71%, and then dropped in March 2021 to a little over 67%.

The concern about voter fatigue was largely unfounded throughout the crisis.

Israelis will likely show up en masse again.

Voter turnout in Israel is at an average rate for democratic countries, with a decrease in the past two decades.

It is not compulsory to vote in Israel, but to encourage voters to turn out, they are given an extra vacation day.

There is no possibility to vote through the mail. There is also no possibility to vote in advance, except for Israelis serving abroad in an official capacity and their families, Israeli sailors on Israeli ships at sea, and soldiers. Experts believe a change in this could increase turnout.

After a brief one-year break from political paralysis, the country finds itself once again in the midst of a campaign that will again revolve around former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his ability to lead the country.

Netanyahu, who is on trial on corruption charges, is seen by many as unfit for leadership. When members of his own right-wing camp also voiced opposition to him, an unsolvable political conundrum was born. Leading the Likud, long Israel’s largest political party, Netanyahu was repeatedly unable to form a coalition. Instead, the country went to back-to-back elections, until an unlikely coalition was formed by Bennett and the current transitional prime minister, Yair Lapid of the Yesh Atid Party.

Netanyahu denies the charges against him and with popular backing, he continues to lead the right-wing bloc. The debate regarding Netanyahu is divisive, but it also helps to ensure reasonable rates of participation in the democratic process.

While polls conducted by the Israel Democracy Institute (IDI) throughout the previous election campaigns showed a decline in interest in the process, the turnout showed otherwise.

“The fact that there are a lot of elections in itself does not affect the turnout,” said Prof. Ofer Kenig, a research fellow at IDI. “Voter fatigue appears to be balanced by the polarization in the political system.

“From election to election, the sides had a lot to lose and emotions ran high. When there is such polarization, it pushes people to vote,” he added.

Dr. Moti Gigi, a sociologist and head of the Communications Department at Sapir Academic College, near Sderot, said, “Voters understand the importance of every single vote, especially when there is a fierce competition. In these cases, we even see an increase in voter turnout.”

“Voters understand the importance of every single vote, especially when there is a fierce competition. In these cases, we even see an increase in voter turnout.”

Dr. Moti Gigi

Throughout Israel’s history, in campaigns when the winner was clear, turnout was lower.

While the Likud has consistently maintained its status as the largest party, Netanyahu’s inability to form a coalition highlights how much each vote counts. According to recent polls, Israel’s longest-serving prime minister is just one or two mandates shy of forming a coalition. Netanyahu will need voters who did not show up last time, mainly from the geographic periphery, to show up.

Many believe that if Netanyahu can’t form a coalition this time, he may be finished politically. That could push his supporters and also his adversaries to the ballot box.

In the past year, the Likud consistently rose in the polls, showing greater support for his leadership. Still, his ability to assemble a majority in the Knesset is far from certain.

A greater question mark regards the turnout among Israeli Arabs. Making up just over a fifth of the population, turnout in the sector has fluctuated and has a great influence on the end result. In the last election, Arab voting plummeted.

“Arab voter turnout in the last election, which was below 45%, is a warning sign,” said Kenig, “It means 20% of the population in Israel feels the election process is irrelevant for them and reflects a general feeling of alienation toward the political system. It is unhealthy for Israel that such a large portion of its population does not participate in the game.”

The historical participation of Ra’am, an Islamist party, in the Bennett coalition will likely have an effect on those numbers.

“Arab society underwent a major process with the entrance of Ra’am into the coalition,” said Gigi. “This may even lead to a sharp increase in turnout in the upcoming elections.”

However, disappointment with the outcome of Arab participation in the government may have the opposite effect. While the Bennett government allocated an unprecedented budget for the Arab citizens, polls recently conducted by the Statnet Research Institute suggest voting among Arab will plummet.

There are a number of contributing factors.

“The Arab population did not see tangible achievements as a result of Ra’am’s presence in the coalition,” said Yousef Makladeh, CEO of Statnet. “But also, the split between the Arab parties makes the identification of a common, coherent political rival more difficult.”

When there is infighting between the Arab parties, voters tend to stay at home. However, incitement by the right-wing bloc against Arabs, as was seen in previous elections, could encourage people to vote.

Four months away from the election, everything is subject to change.

Tired of an endless election cycle that produces political paralysis, Israelis might surprise with a high turnout.

“This is a critical election,” said Gigi. “People want to see a clear decision and not more elections. They feel committed to vote, each for their own bloc.”