On Tuesday, November 1, Israelis head to the polls for the fifth general election in less than four years with no certainty that the political deadlock is about to end anytime soon.

Fed up with the never-ending cycle of elections followed by political stalemate, the campaign has generated little enthusiasm with the public. With the Jewish High Holy Days following the quiet summer months, the campaign really got underway in earnest only during the last few weeks.

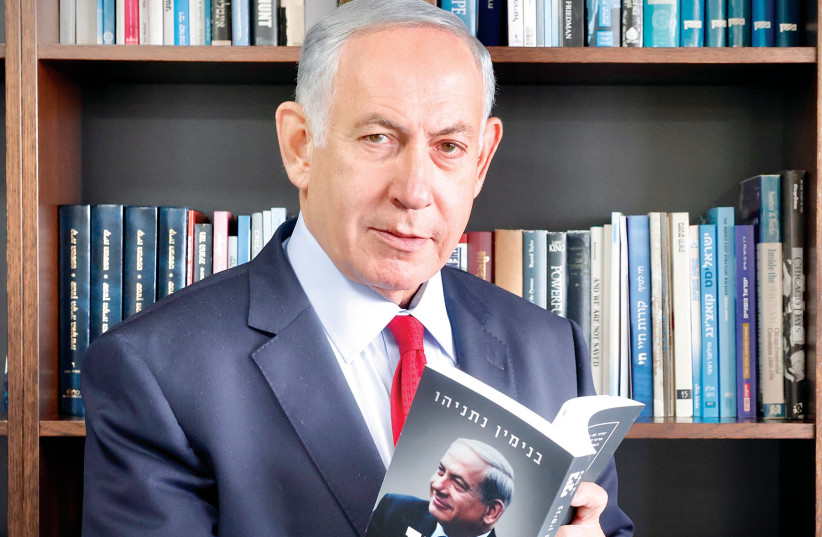

Israel's fault line: Benjamin Netanyahu

Once again the fault line revolves around one man: former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The two opposing blocs are divided into the “Only Bibi” camp and the “Anyone but Bibi” camp, alluding to the Likud leader’s nickname.

The right-wing and religious parties in the Netanyahu bloc, led by the Likud, comprise the far-right Religious Zionist Party headed by Bezalel Smotrich; and the two haredi parties, United Torah Judaism and Shas.

The anti-Netanyahu bloc is made up of Prime Minister Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid; the National Unity Party led by Defense Minister Benny Gantz; Avigdor Liberman’s Yisrael Beitenu; the two left-wing parties, Meretz and Labor; and the United Arab List led by Mansour Abbas.

The polls predict 59 or 60 seats for the pro-Netanyahu bloc – one or two seats short of a majority in the 120-seat Knesset; 56 or 57 seats for the anti-Netanyahu camp; and the remaining four seats likely to go to the Hadash-Ta’al Arab party.

Israel's Arab parties struggle to clear the threshold

The good news for Netanyahu is that both the Arab parties projected to win seats are close to the minimum 3.25 percent threshold required to gain four seats in the Knesset.

If either one of the Arab parties fails to pass the threshold, then the Netanyahu bloc is almost guaranteed a slim Knesset majority.

The United Arab List, which was part of the outgoing government, is projected to win four seats. But the position of Hadash-Ta’al is more tenuous, and the list’s fate may depend on the turnout among Israeli-Arab voters, which is traditionally lower than the Jewish voter turnout.

Voter participation in the last election within Arab society reached an all-time low of just 46.5%, which reflected a 20% drop in the space of a single year, after voter participation stood at 65% just the year before.

A third Arab party, the more radical Balad, split from the Joint List with Hadash-Ta’al earlier in the campaign and is polling well below the threshold.

Despite the danger facing the Arab parties, they failed to sign surplus vote agreements, meaning that tens of thousands of votes in the Arab sector will go to waste. The Netanyahu bloc hopes that the final push in the last week of the campaign and a well-organized effort on Election Day, combined with a low turnout in the Arab sector, will be enough to clinch a wafer-thin Knesset majority.

Does Yair Lapid have any realistic hope this election?

In contrast, the best the anti-Netanyahu bloc can realistically hope for is to block Netanyahu’s return to power while Yair Lapid stays on as caretaker prime minister.

Under such a scenario, will the pro-Netanyahu bloc remain united if Netanyahu fails to deliver for the fifth consecutive time? Will the Likud’s “natural partners” abandon Netanyahu to form a government with Lapid or Gantz? Will there be a revolt within the Likud against the party’s uncontested leader?

The center-left block has no path to forming a government without the support of Hadash-Ta’al. Whereas Lapid has refrained from ruling out the option of forming a government that would rely on support from Ahmad Tibi and Ayman Odeh from outside the coalition, Gantz pledged not to form a government with Hadash-Ta’al, saying that the National Unity Party would not join any such government, even if it were to be formed by Yair Lapid.

Itamar Ben-Gvir and the growing support for Israel's far Right

The most significant trend during the election campaign has been the surge in support for the radical Itamar Ben-Gvir, head of the far-right Otzma Yehudit (Jewish Strength) and number two on the Religious Zionist Party list.

The polls predict some 14 seats for the Religious Zionist Party, making it the third-largest party behind Likud (circa 31) and Yesh Atid (circa 23).

ITAMAR BEN-GVIR, once considered an extremist beyond the pale, will be able to demand a key ministerial portfolio if Netanyahu is given the mandate to form a coalition.

Ben-Gvir came to prominence as a leading supporter of slain Rabbi Meir Kahane, who served in the Knesset from 1981-1985 and whose Kach party was then banned for its anti-Arab racism. The army refused to enlist Ben-Gvir because of his extremist views.

In 1995, a few weeks before the assassination of prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, he appeared on television brandishing a Cadillac emblem stolen from Rabin’s car and declared: “We got to his car, and we’ll get to him, too.”

“We got to his car, and we’ll get to him, too.”

Teenage Itamar Ben-Gvir about Yizhak Rabin

Ben-Gvir had a photograph hanging in his home of another supporter of Meir Kahane, settler Baruch Goldstein, who massacred 29 Muslims at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron in 1994.

Ben-Gvir has been indicted more than 50 times, mostly on public disorder charges, but most cases were dismissed by the courts. His ongoing legal battles prompted him to become a lawyer and make a career of defending right-wing extremists, notably young Jewish settlers from West Bank outposts.

In recent years, after he entered politics, he claimed to have moderated some of his more extreme views. He removed the photograph of Goldstein and urged his supporters to stop chanting “Death to the Arabs,” suggesting “Death to the Terrorists” as more appropriate.

Likud hoped that as the election campaign progressed they would gain seats at the expense of the smaller parties in the bloc as happened in previous rounds, but this time the opposite trend occurred. The party of Smotrich and Ben-Gvir steadily gained in popularity, while Likud dropped to 31.

The US Democratic Party’s Robert Menendez and Brad Sherman have warned that Ben-Gvir’s inclusion in a future government could damage Washington’s relations with Israel.

Ta’al leader Ahmad Tibi threatened to call for an international boycott of Israel should Ben-Gvir receive a ministerial portfolio.

At an election event at Kfar Chabad, Netanyahu refused to go on stage until Ben-Gvir had left, concerned that a photograph of the two together could alienate support from soft-right voters.

Ben-Gvir responded by accusing Netanyahu of preferring to form a broad government with Benny Gantz over one with him, despite statements to the contrary.

Will Gantz sit with Netanyahu?

Netanyahu categorically ruled out such a possibility, labeling Gantz as a “leftist” who says “there is space for a Palestinian capital in Jerusalem.”

Gantz has also ruled out joining a Netanyahu coalition under any circumstances, even though he did join Netanyahu’s government in 2020 in a move that almost ended his political career. “There is no situation in which I will sit with Netanyahu, and I’m not going to negotiate with him,” Gantz declared.

“There is no situation in which I will sit with Netanyahu, and I’m not going to negotiate with him.”

Defense Minister Benny Gantz

Other members of his party have also made it clear that if Gantz makes the same mistake again, he will be on his own.

President Isaac Herzog has already indicated that he will press for a broad-based unity government once the election is over, but it is difficult to see any politician in the anti-Bibi camp willing to agree as long as Netanyahu remains Likud leader.

Both Gantz and Lapid consider themselves candidates for prime minister after the election.

Gantz believes he will be able to attract haredi and possibly some Likud MKs to a coalition headed by his National Unity Party if Netanyahu once again fails to clinch a majority to form a coalition. “There are only two possible outcomes in this election: Either Netanyahu forms a government with Smotrich and Ben-Gvir or Gantz becomes prime minister,” said Culture and Sport Minister Chili Tropper, a confidant of Gantz.

However, at this juncture, all the parliamentarians in the Netanyahu bloc are swearing allegiance to the former prime minister. The Likud failed to ditch their leader after the last four elections, and his grip on the party is now stronger than ever, with no clear alternative leader waiting in the wings.

Gantz hoped that the decision by former IDF chief of staff Gadi Eisenkot to join his list would lead to a surge in popularity, but this failed to materialize and the National Unity Party has polled consistently around the 12-13 seat mark, significantly lower than Yesh Atid.

In contrast, Yair Lapid’s party has made gains during the campaign, managing to rise from a projected 20 seats at the start of the campaign to 23 or 24. “Only one of the two larger parties should form the next government,” Lapid said.

The National Unity Party said in response, “Lapid has no government. It’s a matter of numbers, and no one plans to form a government with Hadash-Ta’al. The next government will only be formed by someone who can break up the Netanyahu bloc and unify the nation: Benny Gantz.”

Two weeks before the election, Lapid made it clear that he was seeking votes from within the bloc, including from Labor and Meretz supporters. “I believe,” he said, “that in the next government, it is necessary that Yesh Atid be big and strong so that the government will be stable and not fall apart.”

But this high-risk strategy could potentially push either or both the smaller left-wing parties, who are polling at around five seats each, toward the electoral threshold. Meretz leader Zehava Galon responded that Lapid’s focus on Yesh Atid could well pave the way for Netanyahu’s reelection.

The issues facing Israel and an attack on the courts

THE LIKUD tried to highlight a number of issues during the campaign: the cost of living; the turbulent security situation; the pending maritime border agreement with Lebanon; and the reliance of Lapid and Gantz on the support of Arab parties. However, none of these issues had a significant impact on the polls.

The message of the anti-Bibi camp focused on the alleged dangers of an extremist Netanyahu-Ben Gvir government and the threat to Israeli democracy. At the center of the campaign was the allegation that a Netanyahu government will undermine the independence of the judiciary, allowing for the corruption allegations against Netanyahu to be overturned.

Netanyahu is accused of fraud and breach of trust in three separate graft cases and bribery in one of them in a trial that is expected to continue for at least another two years. He denies all the charges against him, claiming he is a victim of a witch hunt by the Left, the media, the judiciary and law enforcement agencies in order to keep him from power.

Curtailing the power of the judicial branch has been a central policy platform of the pro-Netanyahu camp during the campaign.

In mid-October, Religious Zionist Party leader Bezalel Smotrich and his colleague, MK Simcha Rothman, unveiled the party’s “law and justice” plan to reform the judicial system. The two men presented a litany of grievances about the current state of the judiciary, including what they described as the excessive power it wields. Their plan includes a range of measures that would shift the balance of power into the hands of the legislative and executive branches of the government.

The plan would strip the High Court of Justice of most of its power and give the Knesset the power to overrule a Supreme Court ruling by a majority vote; the composition of the Judges Selection Committee would be changed, and it would be controlled by the justice minister; the attorney general’s powers would be divided so as to be held by three separate individuals: and, critically, the crime of fraud and breach of trust would be annulled.

“A right-wing government has no right to exist if it doesn’t abolish the offense of fraud and breach of trust.”

Likud MK David Amsalem

“A right-wing government has no right to exist if it doesn’t abolish the offense of fraud and breach of trust,” said Likud MK David Amsalem, who wants to serve as justice minister if the Likud forms the next government.

The Religious Zionist Party claimed the reforms would not retroactively apply to Netanyahu, and Likud says it “would not impact” his trial. However, if Netanyahu’s alleged transgressions are decriminalized, it is difficult to see how his trial could continue.

Netanyahu has promised the public that if he secures a 61-seat majority, he will head a stable government over the course of four years. But even if he emerges victorious and secures a majority of one or two seats, he certainly won’t be the prime minister of a stable government. He will face an entirely new headache as the leader of a narrow right-wing government with a resurgent Religious Zionist Party as his dominant coalition partner.

The animosity the leaders of the anti-Bibi bloc feel toward Israel’s longest-serving prime minister has only grown over the years. This time, they won’t be there to rescue him.

Those hoping that the November election will finally put an end to the country’s chronic political instability should think again. ■