On Simchat Torah, Oct. 7, 2023, our world changed forever. As Israelis and Jews all over the world, we have tried to come to grips with the trauma we collectively suffered that day.

We have tried to continue our lives as normally as possible despite the ongoing war with Hamas in Gaza, which has dragged thousands of ordinary Israelis away from their homes and their lives; the constant protests worldwide, and the increase in antisemitism – both online and in the flesh; we know that our lives will never be the same again.

This is also true of our Judaism. Our religion, which has so many powerful concepts, has been changed forever. Shabbat, one of the central tenets of our faith, has changed for many people.

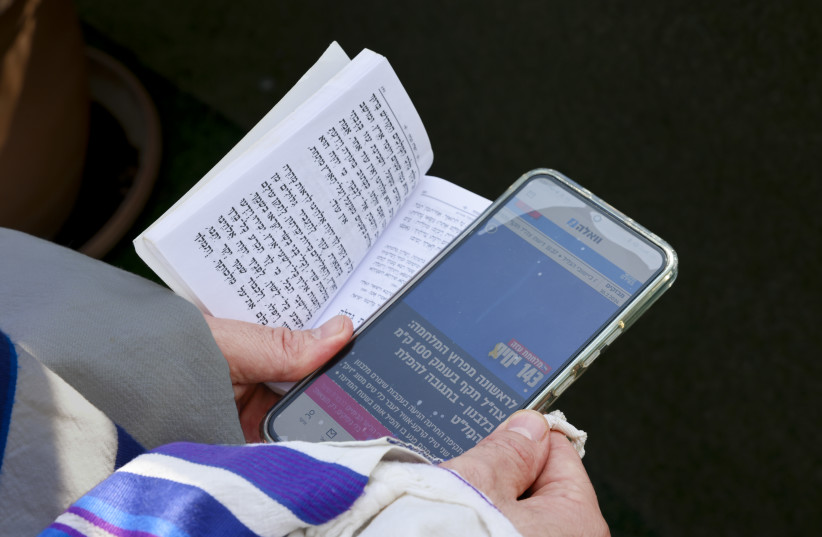

As hundreds of Hamas terrorists crossed the border into Israel and rockets rained down on Israeli cities on that fateful day, people all over the country were celebrating the festival of Simchat Torah – rejoicing of and with the Torah – which fell on Shabbat. Religious Jews, whose cellphones, due to a prohibition against actively using electricity, are normally turned off for those 25 hours, found themselves reaching for their phones to check in with loved ones, to answer their call for military service, or to find out what was really happening in the country.

A survey conducted by The Jerusalem Post looked at Israelis’ relationship with God and Judaism and found that a third of those asked said their faith had been strengthened.

The survey also revealed a significant shift in cellphone usage on Shabbat since Oct. 7 and sheds some light on evolving attitudes toward technology and religious practice, particularly in the context of heightened security concerns in Israel.

The survey

According to the survey results, a striking 68% of respondents reported regularly leaving their phones on during Shabbat since Oct. 7. This represents a substantial departure from traditional norms, where phone usage is typically forbidden during this holy day. Moreover, a majority of respondents (57%) stated that they correspond more by phone during Shabbat since Oct. 7, while a similar 56% reported checking messages and other updates.

Interestingly, the data also revealed gender and age-based differences in phone usage on Shabbat. Women were more likely to leave their phones on during Shabbat, with 72% regularly doing so compared to 65% of men. Additionally, respondents aged 60 and above showed a higher propensity for checking their phones, with 65% reporting this behavior compared to younger age groups.

Religious affiliation played a significant role in determining phone usage patterns on Shabbat. Among religious respondents, 56% reported regularly or occasionally having their phones on during Shabbat since Oct. 7. This trend was particularly pronounced among Masorti (traditional) Jews, indicating a willingness to adapt religious practices in response to changing circumstances.

Regarding correspondence, 11% of religious respondents and a staggering 76% of traditional Jews reported corresponding by phone on Shabbat at least once. In contrast, only 2% of ultra-Orthodox respondents engaged in similar behavior, reflecting stricter adherence to traditional prohibitions against phone usage on the weekly holy day.

Similarly, when it came to checking messages, 13% of religious respondents and 77% of traditional Jews admitted to doing so on Shabbat since Oct. 7. Conversely, only 6% of ultra-Orthodox respondents acknowledged checking messages during this time, underscoring the divergent approaches to technology within different religious communities.

The study was spearheaded by Dr. Menachem Lazar of Lazar Research in collaboration with Panel4All.co.il, an Internet respondent panel. It was conducted between February 5 and 6 and drew responses from 512 individuals, providing a representative sample of Israel’s adult Jewish community. With a margin of error capped at ±4.3%, the findings offer a glimpse into the nation’s soul-searching journey in the face of adversity.

‘Pikuah nefesh’

One of the key concepts that kept appearing during the Magazine’s investigation, and a major notion to understand since Oct. 7, is that of pikuah nefesh, a fundamental principle in Jewish law that prioritizes the preservation of human life above almost all other religious commandments.

Pikuah nefesh literally means “saving a life” in Hebrew. The concept stems from the understanding that human life is sacred and must be protected and preserved whenever possible.

This obligation to save a life overrides virtually all other religious laws, including the prohibitions against certain actions on Shabbat and other holy days, such as not using one’s cellphone.

It is why medical first responders, such as those who volunteer for Magen David Adom, United Hatzalah, and soldiers in the IDF, are allowed to use their phones on Shabbat for this purpose.

“This unusual security situation we are currently in expands the definition threshold of pikuah nefesh,” writes Rabbi Menachem Pearl, head of the Zomet Institute, a national center that brings together halachic (Jewish law) authorities and technology experts to integrate new technologies into the halachic parameters of day-to-day Jewish life in Israel and around the world.

“In a location where the Home Front Command siren is not heard, one must ensure the presence of an activated cellular phone with a fully charged battery before the Sabbath.”

The public’s views

The Magazine asked several people for their thoughts about their cellphone usage since Oct. 7, most of whom wanted to remain anonymous. The overwhelming responses showed that most people are comfortable with having their phone turned on for emergency situations, when previously it may have been off, but that actively using it is still something people are struggling to get used to.

“Starting from Oct. 7, when I heard the multiple sirens in Jerusalem, I realized it was very unusual and worrying – so despite it being chag, I checked the news on my phone quickly thereafter,” one respondent identified as E told the Magazine. “I continued to check throughout the day and even got a call from a friend who keeps Shabbat and had turned her phone on as well, making sure I was okay.

“Since then, most Shabbatot – when walking to [friends’ homes for] meals on Friday night, particularly in the winter dark, I’ve kept my phone on. I usually take it with me when I leave my house, on silent. I like the security of knowing I’ll be alerted of a siren and can also call for help if need be,” she said.

“One Shabbat in particular, a few months ago, we hadn’t had a siren for a while in Jerusalem,” E recalled. “I thought about keeping my phone off, but an instinct told me to leave it on. Lo and behold, not long after I lit candles, my [siren] app went off with a warning; off to the shelter I ran.”

When asked what prompted this change, she stated, “A general sense of increasing my personal security and having a communication device at my fingertips should the worst happen. Pikuah nefesh comes before everything. Also, as a woman, I feel safer in general with it.”

And what of the future? Could E’s phone usage possibly go back to the way it was before Oct. 7? “I’m not sure,” she answered. “I probably will keep it on, at least as necessitated by the specific situation in the country. My perception of Israeli security will likely never go back to the way it was pre-Oct. 7.

“There is no doubt in my mind I’m doing the right thing,” E said confidently. “I’m not scrolling for the fun of it. I’m protecting the life God gave me, which is a mitzvah.” She admitted that keeping the phone on “may feel funny at first – and it’s natural to have neurotic Jewish guilt – but it’s the smart thing to do for many.”

The journalist

“The first Shabbat and Simchat Torah I was forced to work, I felt that updating people about what was going on and giving as much information as possible was something that can be considered pikuah nefesh because the position I hold offers information to a unique target audience. So if we did not supply that information, they wouldn’t get it,” one Israeli journalist who works in Hebrew media told the Magazine.

“It was very complicated because I had to explain to my children, who are young, why I was using a phone,” he explained. “That’s not something that they’re used to seeing, as the phone is usually off on Shabbat. And then, from that moment on until the next Shabbat, I also kept it on and worked a certain period of time because we’re still in the midst of a very dramatic and uncertain event.

“The question is this: If the second you leave your phone on, and you keep going to check to see what’s going on, has your Shabbat suddenly changed?” the journalist asked: “Yes, it’s very difficult to go back. So in the first few months, I was a lot more connected to my phone, but not so much anymore. But it’s something that has definitely affected my Shabbat – and this is something that many people around me also do.”

The IDF officer

One religious reservist officer, who spent the past four months commanding troops in Gaza, explained that on those Shabbatot that he was home from the front, he also had to be available to go back at any moment.

“I’m in a situation where I looked at my phone every time it beeped. But sometimes it would be a WhatsApp from someone in Gaza or near the border with Gaza. Other times, however, it was just a push notification from The Wall Street Journal or a work email, so this kind of blurred my whole disconnect on Shabbat,” he explained.

“The past Shabbat was the first one when I didn’t use my phone – most of the time. I felt helpless, and I wasn’t sure if it was the right thing, but we were not in Gaza anymore. I don’t know how my Shabbatot will be from now on.”

The religious youth

“My personal use changed on Oct. 7,” one young religious woman identified as S told the Magazine.

“During the first round of sirens, in a daze, I figured I would get the news from everyone else around me,” she said. “All that changed when I realized that my family lives not far from the South, and that many of them would have been called up to the army. Around 20 minutes later, during the second round of sirens, I already had my phone out and was checking in on my family.

“When the next Friday rolled around, I made the intentional decision to keep it turned off,” S said. “I figured that if anything big would happen, I’d hear about it. The sense of pikuah nefesh faded past the line of family. As soon as I wasn’t mortally afraid for someone close to me (within reason), I felt comfortable being off line for 24 hours.

“It’s now been four months since then. I usually don’t turn it off and keep it far away from me but rather [leave it] visible in some part of the room,” she said. “It is on vibrate, so I can hear notifications if there is quiet; and other notifications are off, so the only alerts I get are rockets. I think I will revert to not using it at all after the war ends. I hope so.”

The wife

As the survey showed, more women responded that their phone usage has increased on Shabbat since Oct. 7 – for one major reason. Hundreds of thousands of Israeli men were called to military service in the IDF, and their wives, mothers, and sisters who were left behind were more likely to use their cellphones to get any updates coming from Gaza or the northern border.

Understandably, these women were left with a need to understand what was going on and to get as much information as possible. The fear that they must have had over the past four months is not something to be envied.

“I normally turn my phone off every Shabbat, but since my husband was called up for duty, I left it on,” the wife of one man who served for four months on reserve duty told the Magazine.

“While I wouldn’t necessarily take it with me if I went out, I would periodically open it to see if he had called,” she admitted. “Now that he is home for the meantime, I see less of a reason to check it; so although I may keep it on the side, I will not be checking it like I was before.”

Communal changes

“Many people I know have kept their phones on and are taking them with them when they leave the house, particularly women,” respondent E said when asked about those in her social circle. “Some leave at least a radio on in an area they don’t go into often so that it will not disturb the Shabbat quiet.

“None feel guilty about it, as far as I know, since they all have the same understanding of pikuah nefesh.”

Among the religious youth, S stated that “On Oct. 7, most people in my religious circle turned on their phones, and one kept the TV on silent so that the visual element was there, too.

“Since then, it’s been a mix: Some people keep them on, and others decided to go back to no phones,” she said. “It is definitely a debate that has arisen among people in my community. Some people are very forthright with what they’ve been doing or not doing, while others actually don’t share as much.

“For me, as someone who, in terms of phone use, kept Shabbat, stopped and then went back, when the war started, it actually became more of a debate of necessity,” S said. “Shabbat became something I wanted to protect from everything foreign, including the news. It became more of a safe haven than it was before, and I found myself more insistent on keeping it free of phone use.”

The rabbinical perspective

Many people’s memories of the early hours of Oct. 7, especially for those who keep Shabbat, involve the initial moments when they knew something unusual was occurring. In synagogues throughout Israel, as people danced around with Torah scrolls on what was supposed to be a celebratory day, the news filtered through.

“My personal experience was something that I’m not really proud of because I didn’t grasp the situation,” Rabbi Rafi Ostroff, head of the Gush Etzion Religious Council, told the Magazine. “We were in shul, there were sirens, and we went to the safe room. But I didn’t turn on my phone, and I told myself I understand something’s going on.

“Rockets are not something we have never experienced before, so I’m not going to desecrate the Shabbat, and I am not going to change what I am used to doing,” he said.

Ostroff, like many religious Jews, found out later that it was unfortunately not the “usual” type of rocket attack.

“Once they called people up to the army – especially in our yishuv of Alon Shvut [where] they started calling everyone up – we suddenly found out that something serious was going on, but I still didn’t grasp the whole meaning. Only on motzei Shabbat [Saturday night after Shabbat] did I switch on my phone.”

He understood that there was an attack going on and that people who were still keeping Shabbat were already picking up their phones.

“By the next Shabbat, I left my phone on because my children were in the army,” he recalled. “I didn’t take it with me anywhere, but I left it on. By the third Shabbat, however, I had turned it off again, and I said to myself, ‘If something will happen, I will find out somehow.’”

The Magazine asked Ostroff whether he thinks there could be a general shift in the thinking about phone usage on Shabbat during the current conflict, even four months in, to which he answered, “I think the main shift of what has happened is that many people are not actually asking their rabbis and asking their advice. Many parents who have children who were called up kept their phones on during Shabbat; maybe they walked around with their phones on them.

“The truth is that those who saw what was happening, because they turned on the phones first, understood that there’s a war going on. I think that’s definitely caused a whole new thinking of what to do with technology,” Ostroff explained.

“I think it’s amazing when a person keeps Shabbat and succeeds in being disconnected from the world once a week,” the rabbi said. “The only thing is that when there’s a security situation and when mothers are worrying so much about children, it’s very difficult to come and say ‘Switch off your phone and don’t be connected with your sons in the army – and you can’t do anything about it.’ This is something that’s very, very strict – it’s a very difficult demand.”

THE FINDINGS of The Jerusalem Post survey offer valuable insights into the evolving relationship between technology and religious observance during the months since Oct. 7. The decision of so many to increase their phone usage on Shabbat reflects a nuanced understanding of the principle of pikuah nefesh, which prioritizes the preservation of life above almost all else.

While traditional norms surrounding Shabbat observance remain deeply ingrained, the data highlight a growing acceptance of technology as a tool for enhancing safety and communication during times of war.

As Israel continues to grapple with security threats and societal changes, the debate surrounding phone usage on Shabbat is likely to persist. However, the survey results indicate a shift toward greater flexibility and pragmatism in navigating the intersection of tradition and modernity in Jewish life.

The prevailing question looming over these discussions is whether these changes in phone usage on Shabbat will have a lasting impact on Jewish religious practices. While some view these adaptations as temporary responses to the current security situation, others speculate that they may herald a broader shift in attitudes toward technology and Shabbat observance in modern times.