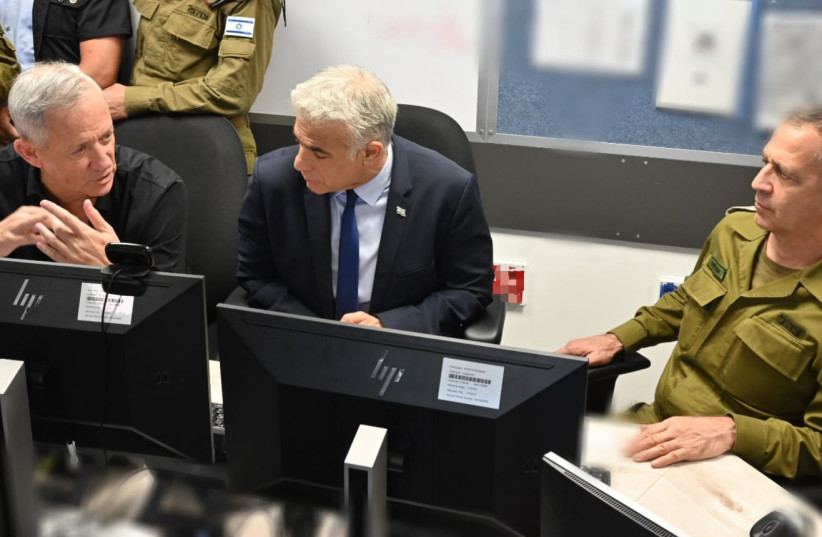

Both militarily and diplomatically, almost everyone in Israel is awarding points to Prime Minister Yair Lapid and Defense Minister Benny Gantz for the weekend Operation Breaking Dawn against Islamic Jihad in Gaza.

But was it legal?

The question of legality is not the usual anti-Israel criticism about alleged war crimes but rather a question of Israeli domestic law, which requires the security cabinet to approve any war or major operation that could lead to war.

Lapid green-lighted the initial attacks to kill Islamic Jihad’s leaders and some of its field combatants in conjunction with Gantz, but without consulting the security cabinet.

So did they break the law?

Almost definitely not. They asked for legal approval from Attorney-General Gali Baharav-Miara to proceed without asking the cabinet, and she told them it would be kosher.

The more interesting question is whether Baharav-Miara gave them incorrect legal advice, and whether someone is toying with the truth between her office and the IDF.

According to Baharav-Miara, the only reason she allowed Lapid to initiate the attack on Islamic Jihad was because the security establishment’s various arms unanimously told her that these attacks would likely not lead to a wider war.

Following Islamic Jihad firing 1,000 rockets at the Israeli home front and criticism from various corners, she strongly implied that if she had known what would happen, and that the security establishment’s estimate to her was wrong, she would have told Lapid that he needed security cabinet approval.

There is, however, a problem with this narrative.

Alongside its initial attack on Islamic Jihad, the IDF spread out Iron Dome batteries across the country, called up reserve units, restricted the movement of Israeli citizens in the south, and put the country on a clear war footing.

So it seems pretty clear that the IDF expected Islamic Jihad to hit back, and hard.

So is Baharav-Miara fudging it? Or did the IDF tell her one thing regarding Islamic Jihad, while acting differently?

Both are possible, but there exists other, grayer possibilities.

Twenty or 30 years ago, it might have been clear what a wider war meant for Israel. But what does it mean today?

Everyone would agree that the summer 2014 and May 2021 conflicts with Gaza represented wider wars. Ground troops were involved, Israel was hit with far more than 1,000 rockets, dozens of Israelis died, and the conflicts lasted 11 days and 50 days respectively, halting all normal life for an extended period.

This weekend’s round lasted for approximately three days, and 1,000 rockets were fired, but not a single Israeli died, and very few rockets hit anything important. Hamas, the real big dog in Gaza, stayed out of it entirely.

This was more analogous to the short Islamic Jihad-focused conflict with Gaza in November 2019.

So do 1,000 rockets fall short of a “wider war”? And might the IDF and Baharav-Miara have had the same conversation but view these concepts differently, with a different understanding about what was at stake?

Extenuating circumstances

There are also some extenuating circumstances. Lapid, Gantz and their lieutenants have said that the element of surprise and their short window of opportunity were critical regarding hitting the Islamic Jihad leaders.

Waiting for a security cabinet meeting would have taken too long, they said, and a sudden convening could have tipped off Islamic Jihad leaders, causing them to go back into hiding.

These are sound – and important – arguments, but had the IDF’s actions led to a wider war, they would not suffice under Israeli law.

Also of note: the security cabinet convened by day two of the three-day operation.

Former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu is fond of accusing his opponents of having double standards for him. There is little question that if he had ordered such an attack without security cabinet approval, he would have been lambasted for an illegal power-grab.

The solution may be that Israel’s law may need to be amended with clearer specifications. This may mean that Israeli law may also need to abandon terms like “war” or “likely to lead to war” to relay with greater nuance what level of risk and suffering the home front can be exposed to without consulting the security cabinet.