Dov was filled with both excitement and trepidation as he walked into the office of the rosh yeshiva. As the newly elected editor of the school yearbook, Shalhevet (The Flame), Dov had decided that this year’s dedication would be to Reb Mendel Wiznitzer, the yeshiva’s founder and spiritual leader. The scion of a large hassidic dynasty, Reb Mendel was his family’s only survivor of the Holocaust. His knowledge of Jewish law was legendary; he could close his eyes and see before him every page of the Talmud, every verse of the 24 books of the Bible. Boys would tremble as they sat before him at bechinot, tests of the tractates they were learning, but would beam with pride when he smiled an approving smile.

As Dov walked into the office, the rabbi was sitting and studying, so Dov quietly sat and waited. He was captivated by the rebbe’s beard. It flowed in snow-white majesty from his face like an Alpine mountain in deepest winter. “What a treasure trove of wisdom and insights must lie behind it!” thought the boy. Little flecks of red could be seen within the beard’s tapestry; these must be the remnants of the rebbe’s struggle against the terrors of the Shoah. How many stories must that beard have heard! How many tears of pain must have washed through it in the darkest of days, yet how many tears of joy to see Jews reclaiming their heritage as they climbed out of the pit of death to new life.

To Dov, that beard was the very soul and essence of his teacher, and a chill went through the boy as he watched the rebbe stroke his beard. No lion’s mane or peacock’s feathers could be more impressive.

For years, the students had refrained from honoring the rabbi with the annual’s dedication, for fear that it would be beneath his stature. But now, on his approaching 80th birthday, the students felt it appropriate that he be given this rightful distinction.

“Dov!” said the rabbi, suddenly looking up. “I didn’t notice you; I was engrossed in this Tosafot. So good to see you! What brings you here?”

Dov gathered his courage and explained the students’ desire to dedicate the yearbook to the rebbe, who pulled at his beard as he mentally dissected the request. Finally, he answered. “Dov, I’m deeply appreciative of this gesture, and I know how important it is to you. Yet, I feel I must decline the honor. The things you would write about me, and all I went through, are perhaps too dreadful to dwell upon. Better to give this compliment to one of our fine staff; they work so hard, yet receive so much less recognition than I.”

Dov was taken aback but pressed on. “You have taught us many times that memory is the key to redemption, and forgetfulness leads to exile. Your story would be a great inspiration for all who read it!” he argued. Reb Mendel stared ahead for what seemed like an eternity but would not be moved. “My decision is final,” he said. “Thank you, and I wish you well.”

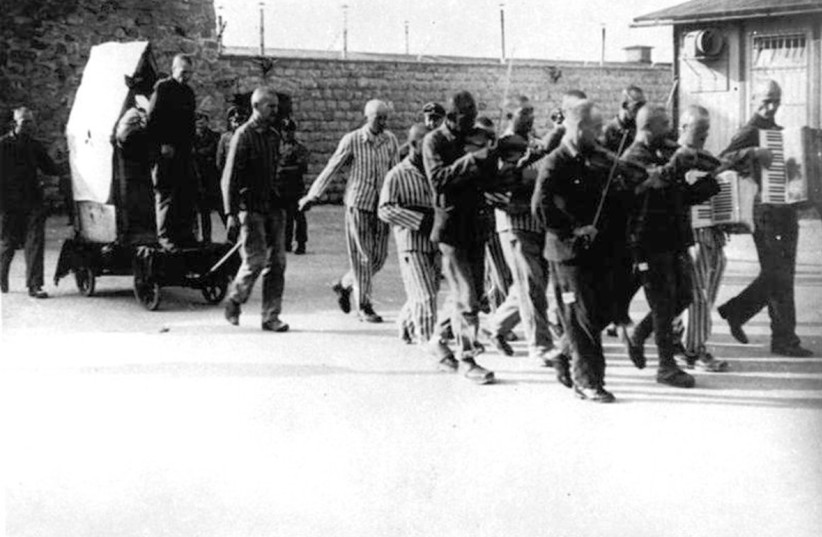

Dov was shaken by the refusal and ran to his favorite teacher, Reb Isaac. “I’m not surprised by this response,” he said. “In the 20 years that I’ve known Reb Mendel, he’s never discussed his past. He must have suffered terribly. He was at the Mauthausen death camp, you know? They say that no Jew ever survived more than three weeks from the time they entered its deathly gates, and yet he survived three years there! It must be excruciatingly painful for him to look back, you must understand.

“But,” said Reb Isaac, “I have an idea. Why don’t you research about the camp, about the Wiznitzer dynasty, and then write the tribute as a surprise to Reb Mendel? Even without his input, you can honor him and celebrate his life.”

Learning about a hassidic dynasty and the Mauthausen concentration camp

Dov was energized by the suggestion and embarked with zeal on his mission. He wrote to survivors of Mauthausen and to Yad Vashem, asking for information on the death camp, and he began to amass all the material he could about the 300-year Wiznitzer dynasty, about the war and about Mauthausen. He was amazed at how so many Jews saw their rebbes as a direct conduit to God, and how their meager material existence was spiritually brightened by these charismatic leaders. They were generals in a Torah army, and every decision they made affected countless lives.

In a book about the hassidic dynasties, Dov found a Wiznitzer family tree. His eyes lit up when he saw the listing for Reb Mendel. “Mendel, third son of Reb Ahron Wiznitzer, born Rosh Hodesh Av, 1928, Poland.” Dov was puzzled. “The year seems right,” he thought, “but Reb Mendel always celebrates his birthday on the fourth night of Hanukkah. Could the book be mistaken?”

As Dov studied more about the inhuman acts of the Nazis in the camps, two emotions overcame him. There was revulsion and disgust at how debased and despicable the human race could be; but at the same time, a feeling of pride – even triumph – at the knowledge that our people died with “Shema Yisrael” on their lips without their spirit being broken. A survivor of the Shoah was living proof that Judaism and the nation of Israel were indestructible. This feeling only heightened Dov’s love and respect for Reb Mendel, and so he began to write his tribute to the rosh yeshiva, a man who stared death in the face, yet lived to tell the tale.

ONE DAY, Dov received a call from a man with a heavy European accent. “My name is Shtern,” he said, “I saw your letter. I was once in Mauthausen. Whatever you read about that place, I could tell you, it was worse, much worse. The living had just one wish – to die without any more pain. I was there two weeks, and then I was sent out because I was an engineer the Nazis needed somewhere else.”

“Could someone survive there for two, or three years?” Dov asked. “Maybe if they were a kapo or somehow spared by the SS?”

Shtern seemed to half-chuckle under his breath. “We Jews have always believed in miracles; unfortunately, I saw few of those in the camps.”

Dov was confused and troubled. How had Reb Mendel survived all those years? Was it, in fact, a miracle, or was there another, more troubling explanation? He could not bring himself to believe that the sainted rabbi would have done anything to harm another fellow Jew. But even as he mentally debated his quandary, a student knocked at his door and told him the rosh yeshiva wanted to see him immediately. Perhaps the rabbi had decided to tell his story, after all.

But Dov was in for a shock. “I must tell you, Dov,” said the clearly angry Reb Mendel, “I am quite troubled to have learned that you are disregarding my words to you and secretly preparing to write about me without my knowledge or consent.” His beard now seemed to be on fire, and his face was no longer one of peace and calm but rather wild with fury. “In fact,” he raged, “you are not responsible enough to be editor of the yearbook; and so, as of this moment, you are relieved of your position!”

Dov was crushed, his mind a whirl of emotions. What had he done? How could he have hurt the man he so looked up to? How could he face his friends? He retreated to his room, a broken soul, and could not eat or sleep for two days.

And then, one of his friends brought him a package from Yad Vashem. Dov looked at it with bitterness and irony; what good would it do him now? Still, he opened it. It was filled with maps and material about Mauthausen, even several volumes of captured German war records. Included in these records were lists of all those who had passed through the camp. Dov casually flipped through the names, looking for that of the rosh yeshiva. When he found it, his heart skipped a beat:

“Wiznitzer, Mendel. Poland. E-1943.” Dov knew that an “E” meant exterminated, eliminated. But if Mendel Wiznitzer had died, who was the man leading the yeshiva?!

A knock at the door interrupted Dov’s train of thought. It was the rosh yeshiva. “Dov,” he said, “I came to apologize for my harsh words. I know how….”

“Who are you?!” Dov interrupted, holding up the paper from Yad Vashem. “Mendel Wiznitzer died in 1943.”

The rabbi seemed to stumble backward at the force of the question. Fear, confusion, shock and then resignation passed over his face. He folded his beard over his mouth as if to guard what he was about to disclose, and then he spoke.

“Dov, I have never revealed this to anyone else before, though I share it each day with the Almighty. My real name is Reuven Landau; I was Mendel Wiznitzer’s best friend. We grew up together and were deported to Mauthausen together. We looked like twins, and at the selection Mendel’s father, Reb Ahron, told us to say we were twins. Somehow, he knew that might help us, and his last word to us before he was murdered was ‘Survive!’”

“And survive we did – until one day when the Nazis made everyone pass through a gauntlet, demanding that we declare that the Germans were the master race, and the Jews the lowest form of filth in the history of the world. I begged Mendel to comply, but he could take no more. He stood tall and told the Nazis, ‘The Jewish people cannot be crushed, and our spirit cannot be extinguished. Your kind will never control us; you are animals, while we are holy.’

“They murdered Mendel on the spot, and I swore that I would survive and keep his name alive. Because we entered Mauthausen together, we had almost identical tattoo numbers – his 52018 and mine 52017. I found a nail and tore my skin across my tattoo, the scar changing the 7 into an 8.”

Pulling up his sleeve to show the tattoo, he went on. “I knew that eventually we would all be called to the selections, so I made my way to another, larger barracks and mixed with those there. Since number 52018 had already been declared dead on the Germans’ records, there was no chance the number would be called again.

“And that is how I survived until liberation and why, as the seeming last of a dynasty, I was given special care and treatment. I knew it was not honest, but I was 15 and I wanted a life of blessings, not curses. I was sent to the best of schools and I worked hard to be the kind of person that Mendel would have been. But now, my secret is finally uncovered, and I shall share this truth and finally end my double life.”

Dov looked upon his rebbe, whose clothes were soaked from the intensity of his confession, and held his hand. “You cannot leave,” Dov said softly. “What you have done is no crime, it is life. God has guided your every twist and turn, and now you are here. Whatever your name may be, whatever your past, you are now a leader of men and a fountain of wisdom that must not be turned off. Did you not teach us that Moses, our greatest hero, had no less than 10 names?! All you have done today is reveal another one of yours.”

The rebbe and the student, their lives forever intertwined, clutched each other with a hardness and a softness that only true friends can know. As they embraced together, the rebbe’s beard covered Dov’s face, and the boy truly became a man.

The writer is director of the Jewish Outreach Center of Ra’anana. jocmtv@netvision.net.il