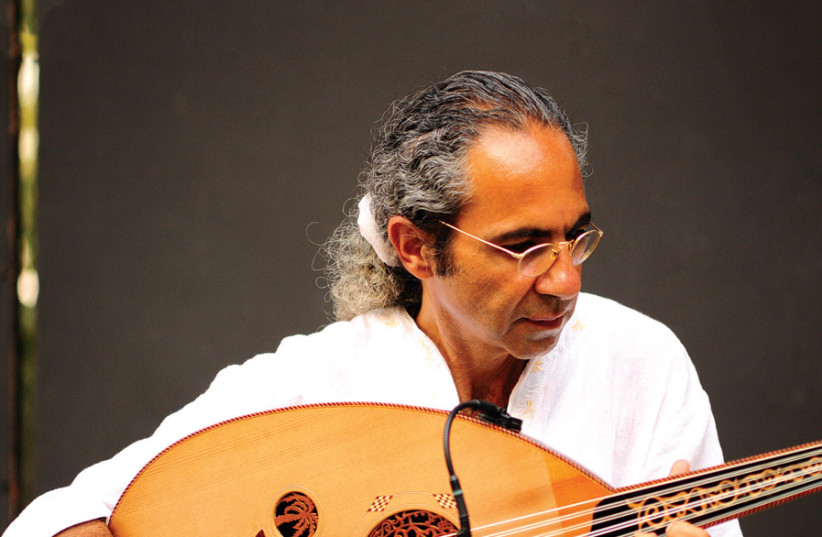

Having a close relationship isn’t a bad state of affairs for a couple of musicians. You could definitely put the personal liaison between Yagel Haroush and Yair Dalal in that category.

Thursday’s Jewish varied musical and textual tradition concert at Confederation House in Jerusalem is called Yedid Nefesh (the Hebrew equivalent of bosom buddies) and features a couple of guys who are just that. “Yair and I both teach in Safed and also in Yeroham, so we spend a lot of time together,” says Haroush. “Sometimes we’ll find half an hour free and we’ll go down to the crater in Yeruham. We’ll play for half an hour and then go back to class.”

That is when the magic happens. “When we play in situations like that, it is the music of the moment. You can’t really record it. That’s what I am always saying to Yair, that the magic comes from the encounter.” It follows, then, that the rest of us may never get to bask in that. “It’s a moot point if you can get that in a recording studio. I don’t know.”

That kind of impromptu tête-à-tête, says the kamancheh (a Persian bowed string instrument) and ney (end-blown flute) player and vocalist, lies at the core of their creative synergy and, indeed, of the entire Eastern musical universe. “One of the things I most love about playing with Yair is the uniqueness of one-time confluences. We constantly return to a basic Eastern theme, which is improvisation. We compose in real-time,” It is, he says, a matter of throwing caution to the wind and just going with the flow. “Then all sorts of things can happen. It is all open.”

That comes, first and foremost, from being fully conversant with the rudiments of your art form. But you also need to have full confidence in your partner-in-musical-arms after paying your dues, individually and collectively. “Yair and I are like mirrors. We are like lights that reflect in each other: What I play is what reflects back from Yair, and vice versa.”

That common bond and shared language is remarkable, particularly in view of the fact that Dalal’s parents came from Iraq, while Haroush feeds off his Moroccan roots. “Yes, we come from different traditions,” Haroush concedes, “but we both grew up here, in the Middle East.” That expansive musical catchment stretch was taken even further by the training each picked up along the road to where they are today. “We learned from all sorts of teachers,” Haroush notes. That is what being Israeli means to him.

The 37-year-old multi-instrumentalist, vocalist and educator made sure he picked up as much as he could from as wide an array of mentors as he possibly could. “I studied classical clarinet. I played in orchestras,” he recalls, adding that spreading one’s educational wings is not such a rare thing in this day and age. “This generation of musicians has studied all sorts of traditions. I studied Arabic music for four years at the academy and studied the Persian tradition with Piris [Eliyahu]. And I studied Sufi music, on ney, in Turkey, and I got Moroccan music at home. That gives you a very broad base.” There were some western commercial sounds in the youthful Haroush mix too. “I liked folk music, and artists like Nick Drake and King Crimson.”

All of that and more colors the way he hears and plays music today. “We often relate to music through the filters we have collected over the years,” he feels. That can surreptitiously find its way into Haroush’s sensibilities mid-flight. “I can be playing some passage with Yair and, not always consciously, I’ll slip in some [Western] harmony. That happens almost without me exercising any control over it. I think that is wonderful.”

Clearly, Haroush does not adhere to catholic musical tastes. He is also of the opinion that is all part and parcel of artistic evolution. “I am not a puritan. You have to know where you are coming from, you have to be connected to the roots of the culture and the music, to be able to create, to advance. But all these traditions were built up over time and, today, we are all adding something to the traditions. That is the beauty of the music.”

Haroush says nothing is sacred. “Yair and I live and create in the 21st century. Music is a living thing.” Dalal also helps to move Haroush along his educational continuum. “It is wonderful to be able to play with him. I sometimes forget we are not the same age.” Considering there are almost 30 years between them, that says much for the power of shared-music-making to bridge generational divides.

SO, AGE difference and cultural familial backdrop notwithstanding, Haroush and Dalal follow a similar pathway and mindset. That also relates to the perception of time and the way to convey emotion, which differs markedly between the Western and Eastern worlds. “There is time in Eastern music. You can impart so much information in a single beat. And that’s not just in music, that applies equally across the whole of Eastern philosophy: Time is circular; you don’t have to rush.”

For example, the latter concept is inherent to taqsim, the musical improvisation that usually precedes the performance of a traditional Arabic piece of music. “It begins with how a musical work opens,” says Haroush. “The taqsim serves as a kind of prologue. It can last a while. I can, for example, play for three or four minutes without disclosing the full scale.” It is very much a matter of creating the context for the work without dotting all the i’s and crossing all the t’s. “I can generate the atmosphere with just the four or five notes of the scale.”

That sets a very different musical and experiential scene compared with, say, a rock concert. Haroush says the softly-softly approach helps to get the audience fully on board. “The first few minutes of a concert are when the audience adopts a different perception of time. That is one of the most genuine elements of the East. And that leads you to a different form of movement in which all kinds of interesting things are possible. The listener can get into a meditative state and become an active listener.”

That is, literally, a world away from the stratospheric energy and excitement levels pumped out at your average rock concert. “There is time and you can address it delicately. We [in the West] are accustomed to being entertained. So as a member of the audience I can sit back in my seat and wait to be entertained.”

The Eastern-music concert scenario is a two-way street and impacts the way the artists go about their business. “The people in the audience become more sensitive to what is happening, and the musicians can play sensitively and gently, without dramas,” says Haroush.

The 27-year-old says he is really looking forward to having another opportunity to mix it with his senior collaborator, and feels blessed by their ongoing union. “There aren’t many, well, as ancient as Yair from which you can drink. I feel he takes me back to the root aesthetics of the music. That means returning to the sound and the delicacy of producing that.”

Haroush believes there are subtle ways to unfurl the magic of music, including its deep spiritual undercurrents. “There is plenty of time. High-standard techniques can come through in very brief flashes. There is a degree of restraint inherent to playing Eastern music which, by the way, is characteristic of Jewish mysticism. There is the idea of holding back, and not revealing the whole secret. You can play the Arabic maqam [a system of melodic modes used in traditional Arabic music] for half an hour without getting to the punch line. That is great art. I am still learning that from Yair.”

Looks like a delectable, engaged time is in store for the Confederation House audience.

For tickets and more details: call *6226 and visit http://tickets.bimot.co.il or call (02) 539-9360 and visit http://www.confederationhouse.org