Anyone, say, over the age of 60, remember the transition from LPs to CDs? Not only did the size of the disc decrease dramatically, the lettering of the liner notes also dropped quite a few font numbers.

Naturally, that didn’t help the older folks with waning eyesight; and most of us, as we progress in terrestrial years, get ourselves specs or just make do with larger formats.

That wasn’t the way Moshe Samter – literally – saw things. When he took relatively early retirement in 1986, at the age of 62, he went for small in a big way. Actually, it took him a while to build up a full head of steam to get into the minutiae of life, but once he made it, there was no stopping him.

Some of the results of Samter’s attention to detail have been on display, for the past close to six years, at the Great Mini World in Yokne’am, which offers a delightful array of deftly crafted miniatures.

The museum opened for business, in the heart of the local hi-tech quarter, in 2016, when Samter was a pretty hale and hearty 93-year-old.

“He died in August 2020, at the age of 97,” says his daughter Anat Orland, who, clearly, inherited some artistic baggage. When she’s not at the museum, she makes a living as a graphic designer specializing in decorative furniture for the home and the office.

Samter kept himself gainfully engaged as long as he possibly could.

“My father worked on large pieces until the age of 93,” Orland explains. “After that, for a couple of years, he worked on small items, parts of figures and so on, which we sell here.”

Thankfully, the miniatures man lived to see the museum take on corporeal form. He was very much involved in the setting-up process and, later, in the day-to-day modus operandi.

“He was really busy with that,” says his other daughter, Edna Yahav, a painter and sculptor. “He was here for over four years. He had a diary, and he kept an orderly record of all his appointments and the groups that visited.”

That was par for the genetic cultural course for the Yekke who made aliyah with his parents, from Germany, in 1936, at the age of 13.

Mind you, his primary means of keeping the wolves from the familial door had little to do with the creative activity into which he poured his talent, heart and soul for the last three-plus decades of his life. But there was, at least, a nominal connection to his professional skills output.

“He worked as a bookkeeper,” says Orland. “But he also trained as a bookbinder.” And there are quite a few tomes, albeit diminutive, on show at Great Mini World.

THE MUSEUM is neatly divided into thematic sections. These include rooms, houses, furniture, music, art, religion, shops and – yes – books.

The attention to detail, and Samter’s ability to put his ideas into tiny physical form, are quite staggering.

In one work, for example, there are three cabinets stacked with tomes with fetching colorful binding. It makes you want to extend a gentle hand, carefully pull one out and deferentially leaf through it. That isn’t a practical notion, not just because of the size of the artifact but, of course, because there aren’t any pages to turn. But seeing is almost believing, and the books of the shelves make for convincing and utterly charming viewing. The bookkeeper duly became a bookmaker, of sorts.

Samter’s second skill set was also put to good use at the museum, with a Lilliputian bookbindery on display complete with all manner of cutting implements, presses, paper rolls, other materials and even three employees caught in mid-graft. The man evidently had an insider’s knowledge of the business in hand.

He was also a wiz at the real deal.

“See that machine for gluing books?” says Yahav. “He built that.”

“He didn’t just build it; he invented it,” Orland interjects. “He didn’t copy a machine like that. He designed and created it himself. He also built a book sewing machine.”

“And an embossing machine,” Yahav adds.

THE DAUGHTERS’ pride in their late dad’s beloved creative pursuit is palpable. They are as enthused as Samter was about the exhibition space and the little gems he produced for all to enjoy.

Since it first opened its doors, Great Mini World has drawn people of all ages, including schoolchildren, and visitors from abroad to marvel at the pint-size exhibits.

“He spoke German and had very good English, and he’d do guided tours in both languages, in addition to Hebrew,” says Orland.

The sisters, much as their father, are also keen to get visitors on board. That also informed the snack I was offered when I arrived.

“Why do you think we gave you pistachio nuts?” Orland poses.

I’d assumed it was just a normal act of benevolent hosting. In fact the nonedible part plays an important part in the hands-on museum curriculum.

“We give all our workshop participants two pistachio nuts, and we teach them the technique of joining the shell halves, without burning their fingers with hot glue,” Orland chuckles. “And once they manage to stick them together, we back off. They can create what they want. Each participant makes a figure, a person or some kind of animal. After an hour everyone leaves with something they have made. That’s very satisfying. For us, too!”

The pandemic shenanigans may have closed the museum down from time to time, but it also had some beneficial long-term effects.

“We added quite a few textual explanations about the exhibits,” says Orland. “Suddenly, we had time to write things out. When our father was still here, he would run around, with his walker, and talk to visitors about what we have here. Now it’s different. He was the living spirit behind this place. He was so passionate about this.”

We also get some of that from a 10-minute documentary visitors get to see at the museum. Samter illuminates his public about his passion, and how it all began for him.

“On our terrace we had an old wicker curtain that broke,” he explains. “I decided to use the wicker and build something out of it. I took the curtain apart and created the first chair... then a table... and eventually an entire room.”

There is also an underlying ecological message to his work. The museum is full of artifacts based on recycled products, and offerings from Mother Nature he picked up on his walks. “Most of the materials come from nature: stones, seeds, leaves and junk – ‘alte zachen’ – stuff we usually throw away. Some of the items I buy in hobby shops – glue, paint and beads, for example,” he said at the time.

Samter said his creative juices were augmented by various inspirational starters. Some creations involved simply copying an image from a painting or photograph, and making requisite adjustments. Others were dredged up from his childhood memory bank, what he termed as the “nostalgia” element to his approach. A classroom scene he fashioned, for example, harks back to his early formative years back in Reichenbach, in eastern Germany. He also says: “Finding an item that kick-starts my imagination, and building the entire model around it – this is the most interesting option.”

ANGLOPHILES WILL find much to pique their interest at various junctures across the display cabinets and shelving vignettes. The sign for one work reads “English country home,” with a tidy front garden and tiled roof, while the interior has a long dinner table under a chandelier, and the upper-floor bedroom has a cute dressing table.

“My father liked British culture,” Yahav notes. A toilet with a chain pull flush mechanism, floral wallpaper, an open hearth and Tudor-style timber elements are all testimony to the enduring cultural baggage Samter took on during his time in the British Army during World War II. Naturally, there is “an English pub” in there, too, and Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol also gets a referential slot.

His meticulousness is evident, in particular, in a captivating pharmacy layout. Not that I, thankfully, frequent such establishments too often in real life, but when I do, especially when the store in question has accrued some vintage, I am enchanted by the rows of bottles and other receptacles on the shelves, with their aesthetic shapes and labels.

Samter does a good job at imparting that olde-worlde ambiance with his chemist’s shop. We also get some idea of how he went about creating the setting.

“There is an explanation here of how he made the bottles,” says Yahav. “He took a sliver of wood, and the bottle top is made of a half a bead.”

The labels even have Gothic lettering. “He used Letraset [typeface sheets] for that,” Yahav laughs. “And here he explains how he made the veneer flooring.”

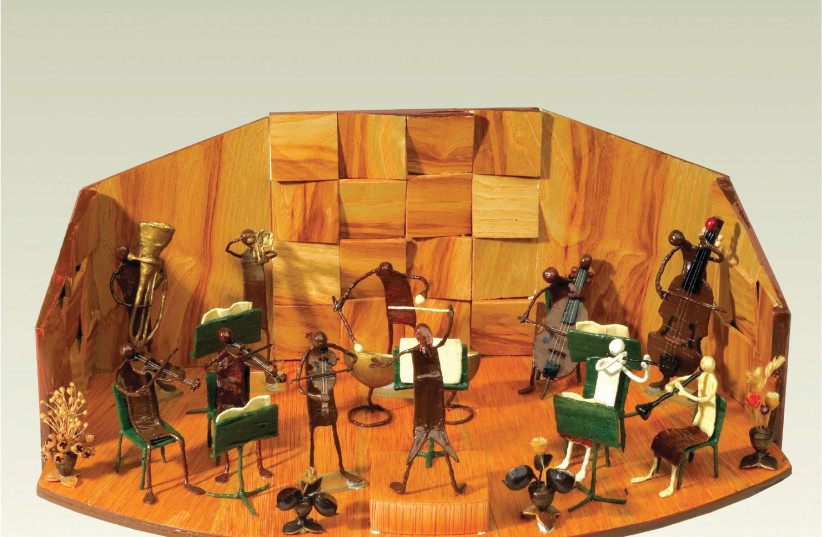

The musical settings are especially evocative. One shows an ensemble in full rhythmic and melodic flight, with the conductor frozen in an animated stance. You can almost hear the sounds coming from the flute, violin, double bass and other instruments on the minuscule stage. The street musician run-out is pretty funky, too.

The museum not only provides a home for the fruits of Samter’s physical endeavor; he also conveys some of his life philosophy. One curious-looking rotund creation has a crescent, cross and Magen David on the domed roof.

“That’s my father’s wishful thinking. He said we all have the same God, so why shouldn’t we all pray in the same place?” Orland observes with a smile.

Samter, it seems, was also blessed with a keen – at times acerbic – sense of humor. That comes across succinctly in his portrayal of the Knesset.

“Look at this,” says Yahav, pointing at a pistachio nutshell figure with a hollowed top half and a gaping lower part. “He makes a statement here – open mouth and empty head,” she laughs. “That’s what he thought of politicians.”

The museum’s patrons, over the years, clearly thought a lot of the place. The visitors’ book is full of enthused reactions. One adult’s response reads: “It was charming and inspirational,” adorned, presumably, by the offspring’s doodles, while another simply says: “It was fun!” That says it all. ■

For more information: www.great-mini-world.com