Art, culture in general, means different things to different people. It may be life-enriching, entertaining, thought-provoking, fun or moving, or spark any of a score or more of other feelings or cerebral jaunts. But for the artists whose work is now on show in the “Hotzim Gevulot” (Crossing Boundaries) exhibition, which opened recently at the David Yellin College of Education in Jerusalem’s Beit Hakerem, one could say that creative endeavor is nothing short of a life changer, if not an actual lifesaver.

The show, which is curated by Naomi Gordon-Chen and was initiated by the college’s Institute for Education of Sustainable Development and Social Entrepreneurship, is a follow-up to last September’s “Breaking the Walls” exhibition at the Arthura Gallery in Kfar Monash, also presided over by Gordon-Chen.

Like its predecessor, the current spread at the college’s social gallery displays works by artists with physical or emotional disabilities of varying severity. The exhibits take in a wide range of subject matters and emotional expression, styles and disciplines, and include painting, photography, video, installations, illustrations and mixed media.

The exhibition moniker is subtitled “The Concealed and Unique in Me,” which, basically, applies to any manifestation of artistic ability. But don’t we all do that? Don’t we all, in general, put on our best face? We all have our personality attributes we put out there for the world to see, things we feel are more “acceptable” and are more in sync with “the norm,” and the other stuff we do our utmost to keep under wraps.

When it comes to people with special needs, that goes double. It may cause us a degree of discomfort to admit it, but the plain and unfortunate fact of the matter is that, by and large, we have a tendency to shun or, possibly worse, to pity those who don’t pass what we view as societal muster.

The curator goes on to perspicaciously note that people who experience challenges and pain, due to emotional and physical problems in their life, are alert to the nature and impact of psychiatric symptoms such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder.

“Their life experience has taught them that the adverse effect of these symptoms exacerbate due to the impact of associative ‘social symptoms,’ such as being labeled ‘mentally sick,’ social discrimination, financial discrimination, policies that impinge on the disadvantaged, alienation, to the point of social isolation of those who appear and behave differently.”

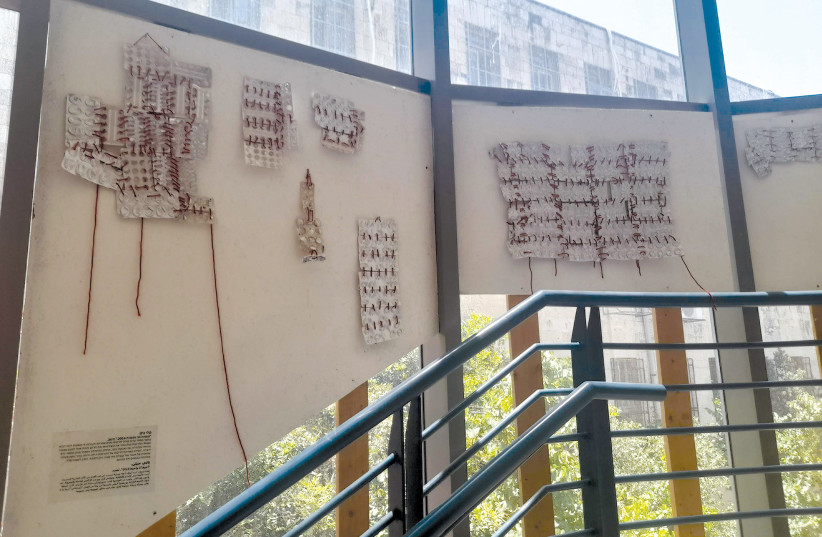

All of the above, and more, comes across in the multidisciplinary spread at the David Yellin social gallery. There are works that offer food for thought, that prick the conscience and, yes, make you feel downright uncomfortable. But, if the latter is the case, try to imagine how the artists themselves feel, what they go through every single day of their lives. One such is an installation by Tali Gilan called I Am Sewing and Sewing 2016, in which she strings together sheets of pills with stitches that conjure up images of the work of a ham-fisted surgeon.

EACH EXHIBIT comes with the artist’s name and the title of the work, and generally with a description of the personal backdrop to the creation. Gilan explains how, for years, she took psychiatric medication which caused her numerous difficult side effects, including, tellingly, blunting her creative instinct. “The medication took my creativity and feelings away from me, and consigned me to a kind of arid and isolated wilderness.”

But Gilan is clearly made of sterner stuff, and brought her indomitable spirit to bear, turning her disadvantage into a creative spawning ground. “I fought that and, as part of the process, I turned my medication into raw material for creation. For me, sewing the empty medicament packaging together was a kind of shamanic action of connection and tying together of things that cannot be joined. It was an attempt to achieve order in chaotic and incomprehensible fields.”

The viewer gets that from the installation, which stretches across the wall by a staircase. Gordon-Chen did a job with positioning the work to its most visual and compelling advantage.

In this PC-strapped age, it is difficult, as an able-bodied white male – is “able-bodied” an acceptable term? – to know how to describe anyone who, for want of better terminology, has to contend with physical and/or emotional challenges. We talk about the “disabled,” and there are people with “special needs.” How best to describe people who do not conform to the normative narrative in a manner that conveys an accurate picture of their physical and/or emotional conditions, without selling them short?

In her exhibition text Gordon-Chen employs an appellation with a distinctly upbeat spirit which, for me, does the trick in the optimum way. “The extrability is designed to enhance awareness of the relationship between society and people with disabilities, with the emphasis on reciprocal partnership.”

The curator notes that, much as the visually impaired are said to develop a keener sense of hearing, going through life with various physical and emotional challenges can help one to identify facilities of which they were not previously aware.

“Extrability is an additional ability or skill that a person with a disability develops due to their adapting to living with their disability,” she explains. “The extra ability, for people with a disability, may dramatically improve their quality of life.” That, she says, can come in handy in all walks of life. “The use and development of extrability in professional fields enables people with disabilities to succeed in integrated work environments.”

There are some striking offerings in “Hotzim Gevulot” across a slew of sensibilities. Some impart a sense of empowerment, others express frustration, anger, beauty, joy or bewilderment.

ADI BEN PORAT’S outsized acrylic work Hibalot (Being Engulfed), for example, strikes the viewers right on the heartstrings. In her exegetical text to the painting, Ben Porat says the painting “conveys the transition from a balanced state to a borderless and uncontrollable manic state.”

She drives her social limbo message home even more succinctly in a mixed media work which comprises a couple of painting frames, hung on the wall in seeming disorder, with the words “Not suited to any framework” running behind one of the frames, fittingly starting inside and ending beyond the bounds of the rectangle.

“My life changed in a single day, physically and emotionally,” she writes in her wall text. “Everything around me just fell to pieces. When I tried to put myself back together, personally and professionally, I discovered that, because of my disability and state of health, I was no longer suitable for any framework.”

Gordon-Chen is keenly aware of that societal downer and sees art, at the very least, as a means for people with special needs to have their say in a world not geared to take too much notice of people who can’t go with the rat race flow. She says that, for the exhibitors, art is “the whole of life. [It is] hope, a way of expressing themselves, to communicate, draw attention and get people to relate to them.”

Considering the sad fact that there are so many people in this country with all kinds of physical and emotional challenges caused, inter alia, by experiences in military settings or encountering violence wreaked by terrorism, it is surprising to hear that people with special needs have to fight so hard to get people – including the political-financial authorities – to sit up and take note. Gordon-Chen calls it “so outrageous.”

THE CURATOR got into the domain of socially oriented art following a cataclysmic event in her own life. She had been working in the field for some years but changed thematic tack after her daughter, Ofir, was killed in a jeep accident in South America. Ofir had been active across a range of artistic disciplines, in writing, dance, painting and sculpture, in addition to what Gordon-Chen terms “immense giving to society and the community.”

She decided to follow in her daughter’s humanitarian tracks.

“After she died she just pulled me there,” she says. “I left a successful career and everything I’d done before, without thinking where I was headed. I registered for a study program on community art at Shenkar [College of Engineering, Design and Art].” That was followed by a master’s at Lesley College – now Lesley University – where Gordon-Chen specialized in the field of challenges associated with generating social change.

She says she hopes “Hotzim Gevulot” engenders “awareness, acceptance, exposure to the topic, equalitarian stances and offering opportunity.”

This, she feels, is a universal issue but a particularly burning one in this part of the world.

“People with physical and emotional disabilities, disabled IDF veterans, people disabled in accidents, those who suffer from battle fatigue, from PTSD, people born with CP or on the autism spectrum, they are part of the mosaic that constitutes Israeli society,” she states. “Arts is a rehabilitative tool for them, and in this exhibition they present a face that Israeli society does not always recognize.”

She says getting that across “is the main objective of this exhibition.”

Each of the participants in “Hotzim Gevulot” addresses that in their own way.

“The works in the exhibition present the viewpoints of artists with disabilities on the place in Israeli society, and examine the ways they cope with the barriers they crash into,” Gordon-Chen continues.

THE WORKS challenge us, but also offer a sense of a beacon shining brightly in the lives of those who tend to be marginalized. “The works present the cracks, the fear of making connections and of social contact. The loneliness, the fragility, the pain, the dreams and hopes, the effect of medication of their lives, and mostly art as a healing tool, and as a creative domain for immersive self-expression.”

There are emotive creations all over the show. Shani Eldar’s Without Skin acrylic painting spells out her sense of vulnerability, as the mother of four battles with MS, while Limor Askenazi’s Hitorerut (Awakening) photograph bluntly communicates “the relationship of control and surrender” the artist has with her wheelchair.

Gordon-Chen wants to show us some of the beauty and gifts such extrability individuals have to offers us and, hopefully, instill a more empathetic and accommodating spirit in Israeli society. “These works express what the artists have to tell [our] society, which created the label that does not allow the majority [of the artist] to resume a normative lifestyle.

“Through their art they simply express their need for support and for embrace, and generous giving, even when there is nothing to draw on, [to express] their battle for survival with few resources, and the small acts of heroism in their daily lives, and just stating ‘I want to fly.’” ❖

“Hotzim Gevulot” closes on July 1.