The worst thing that could possibly happen to an exhibiting artist is when a member of the public blithely strolls past his or her work without giving it a second glance. Art, by definition, must evoke some kind of response. It could be deep emotion, anger, joy or even disgust but, if it doesn’t elicit some reaction, even a knee jerk, it becomes abrogated and emptied of its ability to leave its mark, however minor, on us the consumers.

Ignoring a work by Avner Pinchover is well-nigh impossible. He has several currently up and running in the Mamuta Center at Hansen House, as part of this year’s Jerusalem Design Week.

His spread in the basement space takes in several video works he has accumulated over the years, and a new visual creation called High Voltage. The whole spread goes by the name of Wild Rue, curated by the Sala-Manca Group.

If you are into flora, particularly of the desert variety, you may be familiar with the titular flower that also goes by the Latin name of peganum harmala.

Its wildly disparate, possibly oxymoronic, properties spell out much of what Pinchover is about. I sat with the amiable 41-year-old in the tranquil grounds of Hansen House, after we’d done the rounds of the exhibition, and it immediately became clear that ne’er a sweeter guy was encountered. His personable disposition contrasts markedly with some of his artistic output.

Actually, High Voltage is a far more genteel work than, for example, three previous Pinchover video creations, Riot Glass, Chairs and Spitting. The latter two are also in the Wild Rue mix.

Feral nature

WATCHING PINCHOVER sling school chairs at a plasterboard wall in a gallery gives you some idea of the feral nature of his evolving oeuvre. But when I play, for want of a better mixed metaphor, “the psychologist’s advocate,” and suggest that his relaxed demeanor in everyday life may be due to his unloading pent-up aggression in his artistic endeavor, Pinchover counters that by explaining some of the mechanics behind his craft.

“This is performance art,” he states. “It is not as if, in a fit of anger, I smash a plate in my kitchen at home. This is not something spontaneous. These works are planned a year ahead of time.”

“It is not as if, in a fit of anger, I smash a plate in my kitchen at home. This is not something spontaneous. These works are planned a year ahead of time.”

Avner Pinchover

Point taken, but he expends bucketloads of energy in his videoed acts. Surely that must spark some sort of physiological and psychological change.

That must facilitate some kind of emotional offload. “Yes, there is that aspect,” he begrudgingly concurs, although taking my line of thought and turning it completely on its head. “In fact, this kid on act recharges me and reinvigorates me. This is performance art.

I need to bring myself to performance mode, and I have to demonstrate something just like any actor has to get into character. There is the initial emotion, but there is a lot of processing and preliminary work before I express that, and perform.”

Then again, personal dynamics come into play while Pinchover puts the planning into visceral practice. “There is frustration, both with the chairs and with the [Riot Glass] stones,” he notes.

“With the chairs, to begin with they stick to the wall really nicely. But, after a while, for every chair I get to stick to the wall two drop off,” he laughs. “It was the same with Riot Glass. Sometimes I try to smash the glass and it doesn’t break, and other times I try not to break it and it does break.”

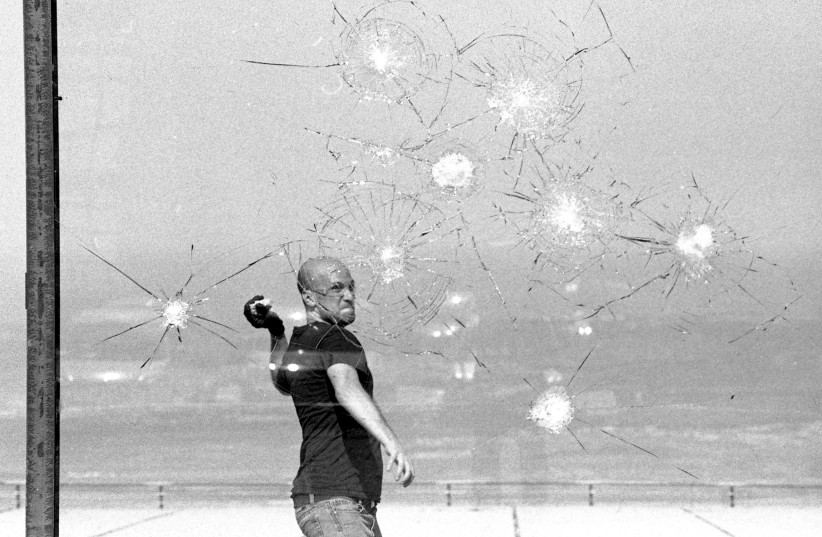

THAT GAVE me the impression that Pinchover video work may be more about achieving an objective rather than about the documented process. Riot Glass, for example, has the artist hurling stones at large sheets of armored plate glass, often used in military situations.

He seems hell-bent on decimating the glass panes, and you can sense and see his frustration when a projectile doesn’t do the business. But, is it more about getting to his destination rather than the journey?

“I want to touch people with my work,” he comes back at me. “This is a sort of communication. The pathway to creating a work of art is important, but I can’t put that above the interaction with the spectators.”

He has street-level credentials in that department. “When I showed Riot Glass in Ramat Gan, there was someone there in the audience, who does not come from the art world, who really expressed their feelings about what I was doing with their body, and their ‘oohs’ and ‘aahs.’

And there was someone at the opening here last week who told me she felt the release of energy of all her anger. I don’t know why. I don’t feel that release until I’ve chucked maybe 200 chairs,” Pinchover laughs. But the sought-for audience response was clearly attained. “That’s my objective,” he eventually declares. “That reaction.”

Pinchover says he gains all sorts of insight from his work. One that surprised me in particular was his observation about accepted gender roles and how women and men relate to emotional offloading. “I have had people say to me, after watching Chairs, for example, ‘When are you going to that next? Let me know.’ And that is almost always, exclusively, women.”

How does Pinchover explain that? Surely, women are generally more adept at giving vent to their emotions, while we males are trained – brainwashed? – to keep our feelings under wraps. “I have the privilege to throw chairs. We, men, can let things go by throwing and breaking objects. We get more opportunities to get the feelings out which we bottle up inside us. It seems women don’t permit themselves to do that as much.” That certainly got me thinking.

NOT ALL the works in Wild Rue are the result of high energy expenditure. One exhibit, in a small display cabinet, comprises a bunch of straggly tendril shapes. “These are roots I found underneath those paving stones over there,” Pinchover explains, pointing to an illuminated spot on the cellar floor. That is yet another example of the balance and counterbalance, yin-yang core of his work. “It was very exciting, and moving, to find something living under this old floor,” he smiles.

We move on to his latest video work, High Voltage. It makes for compelling viewing and we see Pinchover fire plain old fluorescent tubes from a gas-powered launching tube in the direction of electricity cables hanging several meters overhead.

Besides the physical exertion involved in all the screened projects there is always some kind of clash. He examines states of violent interface between different materials, including glass, stone, concrete and spit. The works also make for challenging viewing, in terms of the unfettered action and also the Sisyphean process of achieving the desperately desired end result.

The means to getting there can be mesmerizing, disturbing, riveting and even pleasurable. In High Voltage, Pinchover and fellow artist Nitzan Yulzari fire “fluorescent rockets” from an air-pressure cannon. The bulbs light up as they pass through the electromagnetic field of the electrical cables passing along their trajectory, thereby creating a simultaneously magical and unsettling moment. This is a powerful aesthetic statement, which, somehow – like almost everything that happens in this part of the world – also has a political side to it.

High Voltage had been cooking for quite a while. “It all started from an earlier work from 2017 called Fluorescent,” Pinchover recalls. “That idea began when I was in high school, like Chairs.” The latter was inspired by the students’ seating at Pinchover’s National-Religious school in Haifa. When I was in high school I’d take fluorescent tubes and throw them against a wall. I always remembered the feeling of what it was like to pick up a bulb, throw it at the wall and how they disintegrated right into the wall.”

It was more a virtual-sonic coming together than actual physical absorption of the shards into the vertical brickwork barrier. “It was the sound that penetrated the wall. It was like with Ground Zero – 9/11 – when the buildings fell, they didn’t pile up. It was as if they were reduced from a tall vertical structure into nothing. That’s how it felt with the fluorescent tubing.”

That sensation sat and incubated in Pinchover over the years. “I wanted to recreate that,” he says. And he was willing to go the extra yard to get there. He went to a company that specializes in high-end photography, particularly for the defense forces. “They film all sorts of projectiles to see how they behave across their trajectory,” Pinchover explains. “They film at 3,000 frames a second.”

The resulting video work is nothing short of fascinating, as the lighting implements seem to blend with a wall, and the fragments fly off in every which direction, in something akin to a slow-motion dance with the devil. It also ended with a prestigious career development for Pinchover, when the Tel Aviv Museum of Art acquired it.

HIGH VOLTAGE gradually began to take on corporeal form. “I wanted to find a means of controlling when the bulbs flare into life in flight, in a sort of wireless way and based on a trajectory I choose. It took a while to organize it, but all us artists have ideas hanging around in some drawer until everything comes together to make them happen.”

Pinchover also chose his set with great care. There was also a domestic-social political aspect to it all. High Voltage was shot in the Jerusalem Hills and features the main electricity supply route to Jerusalem and the West Bank. “‘The state of Tel Aviv’ sort of provides the economic support for Jerusalem, and it also sends electric power to Jerusalem. All the electric power plants are on the coast because they [use] seawater for cooling.” Therein lies a subtext to the work’s title, “Metach Gavoah” in Hebrew, which also literally translates as “High Tension.” “There is this tension between the hills and the coastal plain, and between the Palestinian Authority and Israel and, of course, between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.”

There is also tension, in the best and most fruitful sense of the word, when an act of art is created right in front of the public’s eyes, and Pinchover does not rule out the possibility of a live reprise of Riot Glass or, maybe, Chairs. “I really like the feeling of performing something live, while people are watching,” he says. “It is very nourishing. Hadas [Maor, curator of the seventh Biennale for Drawing in Israel, at Jerusalem Artists House in February 2020] and I are still hoping to do Riot Glass live.”

Pinchover is all too keenly aware of the financial considerations, and production logistics, involved in such an undertaking. “I would need to find someone willing to bankroll that, and to help make it happen. Maybe it could be featured in a film festival or something like that. I need to find someone willing to think outside the box, and outside their comfort zone.” Sounds like a pretty spot-on description of the way Pinchover goes about his creative business too, Wild Rue closes on August 19.

For more information: mamuta.org/portfolio/wild-rue/