In his small studio in the Artists’ Quarter in Hutzot Hayotzer, opposite the walls of Jerusalem’s Old City, David Moss sits and ruminates over which of his projects he should pursue. He is surrounded by many of his projects, those finished and those still to be realized. Around him are books he has produced, designs for architectural projects, calligraphy, copies of ketubot and Mizrachs, individual pieces for his minyan project. The list seems endless.

“My work is idea-based and Jewish-based.”

David Moss

Moss sees himself as an artist-designer and educator. “My work is idea-based and Jewish-based,” he reflects. “I realized about the power that these images have educationally and inspirationally. I could say the same thing in a lecture or writing it in a book, but when the art is in front of you and you see it, sometimes magical enters you in a way that doesn’t happen in a lecture. So I have had this parallel career of education alongside the art.”

Just across from his studio is a larger studio called Kol HaOt, run by his daughter Elyssa among others. It works on similar principles, bringing together art and Judaism. Moss explains: “When I work at summer camps and do project-related stuff with kids, we create an object or solve a design problem, which creates this integration. Some 10 years ago, a major Jewish foundation heard about this and asked if I could create a year-long program for day schools in the US.

I created a program with my daughter Elyssa and her co-worker Matt Berkovitz. Together we created a year-long program for day schools ranging from very secular to very Orthodox. We used an art teacher and a Judaic teacher, and two to four instructors. It’s now been going on for about seven years. Today we have about 10 schools and 25 teachers a year. It has been very gratifying. The teachers love it, as do the children. We have them for five days from Sunday to Thursday. It’s fully funded. The teachers do their year-long project with the kids based on the principles they have learned. Then they come all together in May and share their projects.”

The Moss Haggadah and a history of calligraphy and design

Moss is perhaps best known for the Moss Haggadah, an eclectic creation which takes from traditions from all over the world where the Jews have been – North Africa, Spain, Eastern Europe, Israel. It is considered among the best Haggadot that have ever been produced in a market that is very crowded indeed. But prior to this master work, Moss had a long apprenticeship in calligraphy and design.

He began calligraphy after graduating from the Great Books Program at St John’s University, followed by years of study to “bring him up to scratch in Judaism.” While he was at The Hebrew University and at Machon Schechter, he met up with a friend who was a sofer (scribe). “He wrote out a traditional aleph-bet for me, and I copied the letters. Then I started to do squiggles around the letters, and then doing writing for friends.

“Around 1969, David Davidovitch brought out this beautiful illustrated book of the old ketubot, and I naively started asking people who was doing these ketubot now. ‘Oh, they said, that died out about 100 years ago.’ They explained that the ketubah was now a printed form that the rabbis filled in. I was amazed. How could a beautiful, rich tradition like this disappear? So I started doing them for friends,” he recounts.

His pioneering efforts prompted a whole new industry, and today there are many calligraphers and artists who offer these illustrated ketubot. A book on the revival of this art form, which has become a big business, is now in preparation, Moss continued with the ketubot, as well as other small pieces such as Mizrachs (“East” in Hebrew), a cipher for the yearning for Jerusalem that was for most Jews the direction of the ancient city. Mizrachs became very popular, especially among Sephardi communities. But again, none were decorated quite the same way as a Moss Mizrach.

Then around 1981, when he was still doing mainly ketubot – each one took him between a month to six weeks – he approached one of his ketubah clients, Richard Levy from Florida, and asked him if he was interested in an illustrated Haggadah. There are hundreds of illustrated Haggadot going back to the Middle Ages, but Moss had an idea to make a special one-of-a-kind Haggadah. The reason was also practical.

“Such a commission would enable our family to come to Israel with the possibility of settling. That was the motivation. Roz (my late wife) and I had always considered Israel. She was from a very Zionist background. I was not. But it was always a consideration for us. Roz proposed that we go for a year, decide, and then either move there or not. In order to do that I needed a long-term project.

“Levy was a serious collector of old Judaica. He had some beautiful old ketubot, medieval manuscripts and so on. He liked the idea, and we agreed on just three conditions: that it would be fairly large in format; that it should be traditional; and that it be on parchment.”

Although he calculated that the work would take him about a year, it ended up taking three years. It demanded a great deal of research. As a planned one-off project, Moss felt himself very much like a medieval monk being commissioned by one patron to do one book on parchment. “This was the way every book was made until Gutenberg,” he reflects.

“By comparing myself with my predecessor in 880, I wondered whether I was essentially the same or different. In fact, I wondered whether we, as Jews, are the same as we were in 880 or fundamentally different. I came to the conclusion that the answer had to do with Israel. I sensed that this was the essential difference between who we are as a people today as opposed to what we were then. On a personal note, it was connected to our own question as to where we were going to live and raise our children – as Diaspora Jews or Israeli Jews?

“Everything about a medieval German, Spanish, or Yeminite manuscript is very local and site-specific. By contrast, in Israel Jews are gathered from every region of the globe. So a fundamental principle for my manuscript came to be kibbutz galuyot, the ingathering of the exiles. I would bring them all together in my work. Each page is based on some historical precedent, from different places. The text is the Ashkenazi text, but the calligraphy is Sephardi,” he explains.“The first page, for example, is different from any other page in the book. It’s a beginning. The Festival of Passover is also a beginning – a birth experience, the birth of the Jewish people. That’s what gives it power. So what, I wondered, is so special and unique about a beginning?

“In my research at the British Museum, I found a Sephardi Haggadah manuscript on which the first page was just a simple tree. But what is the beginning of the tree itself, I mused. It’s the seed that contains within it everything that tree was about to become. The Exodus, as the birth of our people, was about the miracle of pure potential. The first page had to somehow be a beginning/potential that encompasses the entire rest of the book. To visualize this, I decided to use a very ancient Jewish artistic/calligraphic design form called micography – minute writing in the margins of the manuscript. I created a border that contains the entire text of the Haggadah so that my page one contains the whole book we are about to enter.

“And thus I continued with each page of the manuscript: research, contemplation, original idea, design and execution.”

But even when he had finished and delivered his one-off work, it was not to be the last of the Haggadah. If anything, it was itself a beginning!

“A few years after it was finished, I met Neil and Sharon Norry from Rochester. I showed them photographs of the Haggadah, and Neil’s first response was ‘Can I buy it?’ When I told him that it was not for sale, he said, ‘It’s unacceptable that there is only one copy of this book in the world. It has to be published.’ I told him this was impossible because of the various techniques I had used. To which he said, ‘You’re going to find someone who can print this book to your satisfaction. We’re going into business.’ And thus Bet Alpha Editions was founded.”

After an exhaustive search, Moss found a master printer in Italy. A year and half later, he produced 550 copies of the original, complete with all the special techniques used in the original. Moss also wrote an accompanying text explaining each page’s ideas, research, precedents and meaning and how he arrived at his graphic interpretation. He later did a trade edition, which is now in its fourth printing. Most recently, he produced a beautiful deluxe edition.

Since the Haggadah, Moss has collaborated with other artists on artist books such as the Book of Jonah, the Song of Songs, and the Book of Lamentations, where he received their original etchings or woodcuts and then created a new calligraphic font to complement the artwork.

“The main thing I am currently involved in is my ‘minyan’ subscription plan. This is an ongoing project in which I create original art several times a year and produce it as a series of limited edition, signed and numbered prints. These go to my list of subscribers who appreciate and support my vision. In over 10 years of this project, I’ve sent out more than 40 pieces.

“I called it a ‘minyan’ originally – the Hebrew word meaning the ten people needed for a prayer quorum – hoping that I could find 10 subscribers. Today, that number is 75! I deliberately vary the styles, formats, sizes, and colors to keep each work fresh. Creatively, it’s fantastic, since I have complete freedom to imagine and create. My subscribers love the surprise of getting a new print, artist book or object, together with a pamphlet carefully describing the ideas and thought behind each work,” he says.

Moss draws on all sorts of materials to make these unique creations. They include American quilts, books, and assorted objects. He will include colors based on Kabbalistic formulas. Another of his creations is a print that he calls Homage to the Human Hand, since he so appreciates the gift of the skill of his hands. It’s built up of photos he has taken of hands in museums on his numerous trips around the world.

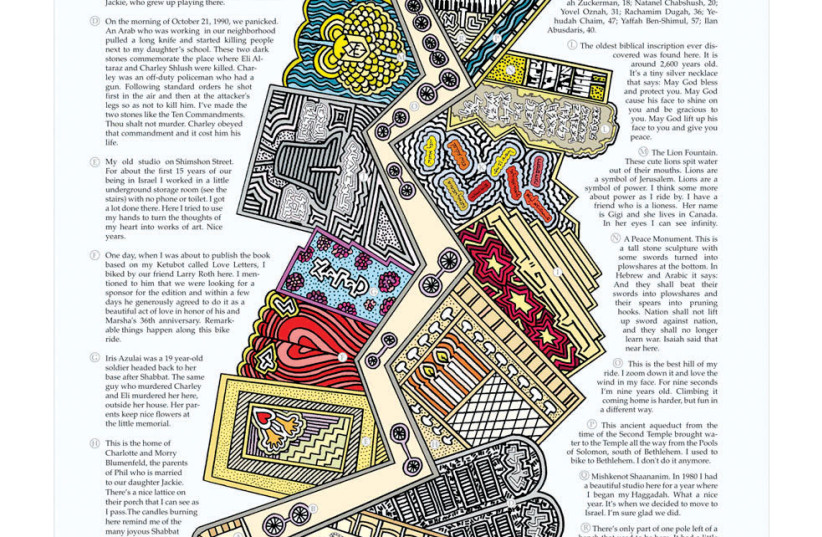

He has also made a number of maps of cities that have a Jewish history. These might include a ghetto or a synagogue, a monument or symbols of people he’s met or experiences from the place and includes his responses to these.

Perhaps it is not coincidental that his eldest daughter, Elyssa Moss Rabinowitz, directs Kol Ha’Ot (The Voice of the Image), which in many ways continues Moss’s pioneering work for future generations to make these surprising but creative connections between the ear and the eye. As Moss himself asks rhetorically: “What’s more Jewish – the ear or the eye?” He answers his own question when he says, “We’re a highly ear-based culture. For a visual artist, that is both an ongoing challenge and an opportunity with unlimited potential to express a deeply verbal, aural, textually based culture visually.”

In his varied activities over the years, Moss has certainly shown that the visual can be a legitimate expression of Jewish ideas, texts and values, along with the written word. ■

Photographs published with permission of Bet Alpha Editions @2023 by David Moss.