Pregnancies take their time. Ask any mother out there. And there’s the morning sickness, hankering after this or that improbable edible combo, and the gradually increasing weight the expectant woman has to lug around with her. That’s even before the labor pains and other trials and tribulations that even the most involved and empathetic of men can only surmise.

Miriam Leibowitz knows all about the above, personally, but the gestation period of “Bikurim” was far more protracted than it takes for a baby to become fully formed and make it out as a full-fledged corporeal being on terra firma. “Bikurim” – “First Fruits” – is an appropriate title for her debut exhibition currently on show in the Salon Gallery of the Jerusalem Theatre. And with Shavuot fast approaching, that makes it seasonally appropriate as well.

Leibowitz is 51, which makes her something of a late starter on the exhibition circuit.

“This is the result of over 20 years’ work,” she tells me when we meet at the theater. “This collection represents my inner journey, using art as a modality for healing and my development as an artist.”

“This collection represents my inner journey, using art as a modality for healing and my development as an artist.”

Miriam Leibowitz

That is clear from the array of figurative and abstract-leaning paintings selected by curator Batsheva Goldman-Ida for Palo Alto, California-born, Israel-bred Leibowitz’s curtain-raiser. There is an evolutionary continuum to the spread of around two dozen mostly acrylic pictures, and a general sense of tenderness, angst, revelation, joy, wonderment, love and a whole range of other life-cycle emotions and sensibilities. That stands to reason, given the two decades that have elapsed, along with the concomitant accrued life experiences, since Leibowitz first put brush to paper or canvas in earnest..

I wondered whether this was a matter of self-belief, peer pressure or anything else she may have encountered en route to finally rolling out to the public at large the results of her deepest soul-searching and her creative gifts as well.

“I’ve been an artist all my life. My mother is an artist. Art is in my blood, but my art was very tight, and I didn’t really know how to express myself,” she states.

You could have fooled me. The works on the Salon Gallery walls convey a sense of immediacy, inner conviction, and a highly personal journey well trodden and aesthetically and evocatively documented.

Leibowitz needed some sort of catalyst to unblock the creative dam. She eventually happened upon the means to achieve her goal and allow her ideas and emotions to simply flow out of her unimpeded and, seemingly, unguided.

“I learned this technique called scribble drawing,” she chuckles. “It is an art therapy technique. You kind of scribble on a page, and you find an image. I feel like I needed that to get over my inhibitions. I had a lot of judgment about my art.”

There were some peripheral obstacles to be overcome, too. “I was dealing with being a mother, and life and my own traumas from life, and I was longing for a way to express myself through art. I did the decorative stuff on ketubot (Jewish religious marriage contracts), sort of useful art. But I was longing for self-expression through art,” she explains.

Studio of Her Own: Fighting the patriarchy in art

THAT SOUNDS like a heaping helping of emotional baggage to try to juggle, and the parental practicalities are, no doubt, familiar to many women around the world. Zipi Mizrachi is well versed in the societal logistics that are often dictated by the male ruling class in a still patriarchal global state of affairs.

Mizrachi is the director of the Studio of Her Own art center that she established in 2010. It was primarily designed to provide a platform for religious female artists who simply had nowhere else to go with the fruits of their creative labors. Since then, the center’s purview, under the steady aegis of chief curator and artistic director Meital Manor, has extended into additional areas of female artistic endeavor and now includes secular women, Arabs and others, from here and abroad.

There is, says Mizrachi, an egregious sense of gender imbalance in the street-level world once you get out of the cloistered environs of higher education and try to make your way where it really matters.

“When you look at Bezalel and the other arts academies, there is a clear majority of women among the students. But that turns around completely when the students complete their studies,” she notes.

It is, she says, simply a man’s art world. “When you look at who makes it, who gains recognition, there are a thousand times more men than women. In the Israeli art sector, there are maybe four or five women artists who are successful.”

The art entrepreneur believes that the asymmetry is due to biological facts of life and the continuing dominance of men in most occupational and other areas of activity.

“Women who, for example, want to realize their motherhood, understand that a career in art is so demanding, as is being a mother,” Mizrachi wryly adds. “Women have several stops along the way when they put their career on hold for a while, and sometimes they find it impossible to get back into circulation in the art world. We are still living in a patriarchal society. That’s a plain fact.”

That may be a challenging obstacle to female artists, but Mizrachi and Studio of Her Own are doing their damnedest to address that lopsided reality. It also dictates the way the center has evolved and now operates.

“We have renovated the garden, opened a café, and we now have a pop-up shop that sells arts and crafts items made by women. We also run workshops where women teach traditional crafts that have almost died out. They teach children, including children with special needs, students and all sorts. Everything is run by women.”

Mizrachi says that women not only have had to grapple with significant career challenges, but those who did manage to navigate their way through the practicalities of balancing family commitments and professional advancement, and clear male bias, are often consigned to the realms of historical footnotes.

“There has been a lot of research carried out on women in all areas of the arts, including female architects who built youth villages here that are still in operation today, and all sorts of buildings and facilities. And there have been female painters, sculptors and in all the disciplines. The names of these women are frequently not even mentioned,” says Mizrachi.

Studio of Her Own is trying to do something about getting the historical facts out into the public domain. “The Ministry of Heritage is now supporting our proposal to act as a heritage center for women’s art in Israel. We are going to work with the National Library, and we are going to set up archives with information about female artists since the beginning of the Hebrew Yishuv through to today.” Anyone and everyone will be able to access the data. “The archives will be accessible, with images and texts about all the artists.”

As any entrepreneur in the artistic and cultural sectors will testify, you need to get yourself out there in order to obtain the requisite support to become and remain a going concern. It is a strange, frustrating, dome scratching-inducing morass which many fail to survive. Mizrachi says it is even more taxing for young female artists looking to achieve some degree of presence in the field. Basically, you need to somehow acquire the wherewithal to keep yourself going for a while and, as an artist in the visual plastic domain, at the very least get yourself an exhibition, before the powers that be will even consider providing you with some financial assistance.

Like Leibowitz, albeit probably for different reasons, there are plenty of budding female artists caught in catch-22 limbo whereby they struggle to get arts facilities to exhibit their works because they don’t have any shows in their bios.

That is another area where Studio of Her Own is now coming in handy. “We closed off part of our balcony to create a space where artists can have their first solo exhibition,” Mizrachi explains. “If an artist has not already had a debut solo show, they are not able to apply to Mifal Hapayis or the Ministry of Culture for support.”

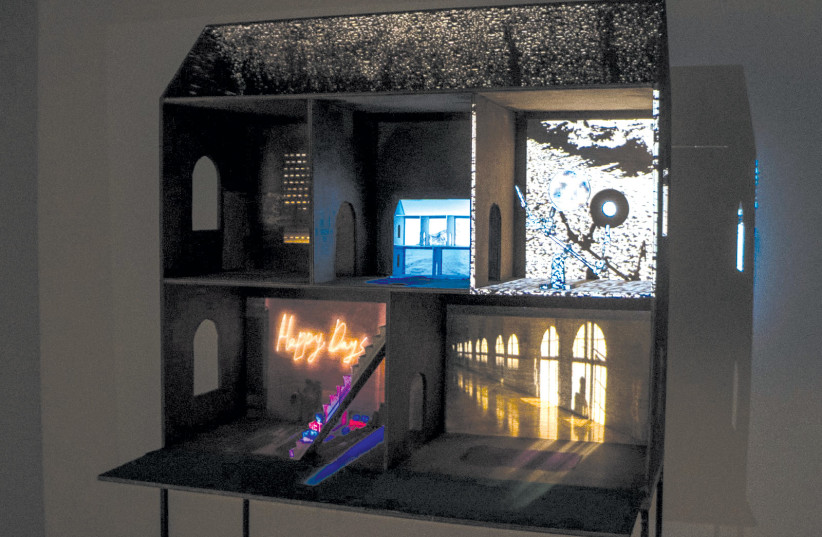

For artists like that, who have the potential and have produced worthy works, it is nothing short of a lifesaver. Mizrachi cites a number of promising and gifted women artists who are now getting well-deserved attention thanks to the woman-oriented facility at the historic edifice on Kaf Tet Be’November Street. The Studio of Her Own roll call includes the likes of young video artist Neta Moses; 43-year-old multidisciplinary artist Shulamit Etzion; and 40something Boston-born, Pratt Institute, New York-trained Yehudis Barmatz-Harris, whose oeuvre to date takes in new media, assemblage and installation.

THE BARBUR Gallery is also doing its bit to push the female artistic boat out there. Earlier this week the unfortunately peripatetic gallery, which currently resides on Herbert Samuel Street near Zion Square, launched an exhibition called “Rest in Power.” The show addresses the pressing issue of violence against women, including murder, and comprises works by visual artist Eden Yilma; New York-based animator Danna Grace Windsor; and Or Segal, who earns a crust as a book illustrator and designer, as well as serving on the teaching staff at Bezalel.

Segal is keenly aware of the predicament of women in society in general and was eager to convey some of that in her slot at Barbur, curated by Lital Marcus Morin and Reut Yeshayahu.

“I relate to the subject of femicide,” she says. “This year, so far, 14 women have been murdered [by their partners]. There has been a crazy increase in the murder of women this year. This exhibition was put together really quickly. I started working on it only a month ago. At the time, there had been 10 murders this year, so there have been four more in the past month alone. That’s crazy.”

In terms of discrimination in her chosen field, Segal says she is in a relatively fortunate position.

“There are a lot of female illustrators. I don’t feel that we are at a disadvantage in this area.”

But the core issue remains. “I find myself, as a woman, wanting to engage in activism and contemporary matters. I find myself relating to how people look at me when I walk on the street, and that impacts on the way I create my art.”

Thankfully, Segal has no firsthand experience of acts of violence, but she feels that she needs to do her bit to impart the seriousness of the situation.

“I am in a pretty good professional place, but the numbers of women being murdered is intolerable. We have to do something about that.”

We certainly do, ASAP, and have to address all kinds of areas of discrimination against women in the process. ❖

For more information: www.jerusalem-theatre.co.il/eng/Exhibitions

studioofherown.com/en/exhibitions_eng/

www.facebook.com/barbur.gallery