Guy Nattiv knows that Golda Meir is a divisive figure in Israel. The director of Golda, the movie that stars Helen Mirren as Golda Meir as she coped with the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, said that as he made the movie, which was released last week, his thinking about Israel’s first and only female prime minister shifted, and he hopes it may change others’ view of the late leader, who has taken much of the blame for Israel’s lack of preparedness for that war.

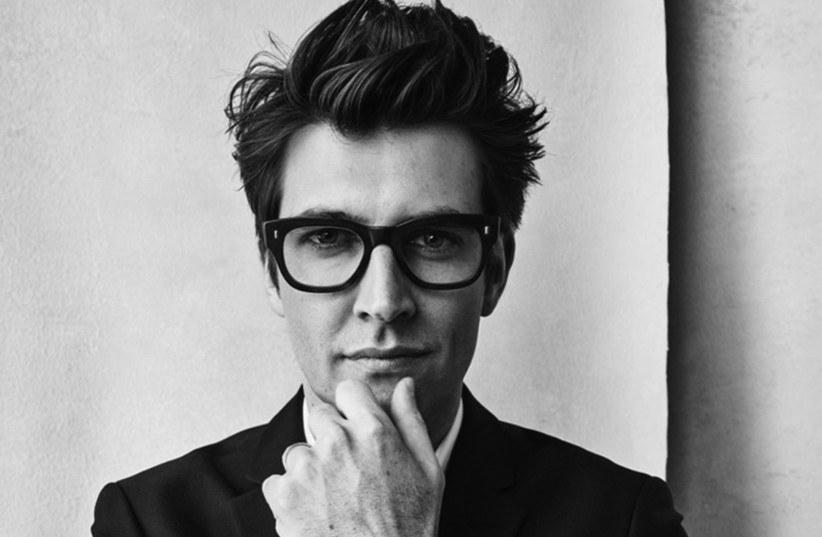

“When I came aboard [the movie], I was very anti-Golda, because I grew up on the notion that she is to blame, that she was the worst prime minister in the history of Israel,” said Nattiv, in an interview from Los Angeles, where he is currently based with his actress/producer wife, Jaime Ray Newman, and their two daughters.

“But the more I researched, the more I worked on this movie, I began to have a more balanced picture of who she was and what she brought to the table. It’s true that she had her faults, but not only her.

“The film is about humanizing this woman... who is the total pariah of Israel. I was explaining to all the non-Jews [working on the film] that she was the Nixon of Israel, she was so hated. You have Rabin Square, you have Ben-Gurion Street, but you don’t have Golda Street.

“I felt that the movie should [have] a different narrative about her. Not cleaning her up perfectly, absolutely not, but because she was a woman, because she was an older lady, it was easy to put her as the face of the failure,” said Nattiv, who won an Oscar for his short film, Skin, co-written with Sharon Maymon, about racism in the US, and then turned it into a feature film.

Nattiv has had a distinguished career making movies in Israel and the US, including the acclaimed films Magic Men and Strangers, which he co-directed with Erez Tadmor.

Originally, Golda, which was produced by Bleecker Street and Embankment Films and written by Nicholas Martin, was intended to be a large-scale, big-budget war film, he said. But then came the pandemic, and the budget was slashed. So Golda ended up being more a character study about Meir and her leadership during the war. This suited Nattiv fine, because it gave him a chance to work more closely with his leading lady.

Casting a non-Jew as Golda Meir

Mirren was attached to the project before Nattiv came on board, he said, but he has no regrets whatsoever about her casting, although some have criticized the filmmakers for not having a Jewish actress play Golda. This controversy was reignited recently after the release of the trailer for the Leonard Bernstein biopic, Maestro, and Bradley Cooper’s fake nose was called antisemitic. In the debate, some pointed to Mirren’s makeup for Golda, which included a nose that made her look more like the prime minister.

Nattiv does not agree with these critics, but he does not dismiss their concerns, either.

“I think it’s a good discussion regarding culture and regarding authenticity,” he said, citing the example of his next film, Tatami, about a female Iranian judoka, which will premiere at the Venice International Film Festival in September.

He co-directed Tatami with an Iranian, Zar Amir Ebrahimi (who is one of the stars as well), and co-wrote it with Elham Erfani, who is also Iranian. He said he felt it was right to collaborate with them on this story, because of their nationality, but he thinks that casting based on religious identity is a different matter.

“What if you say a Jewish actor can’t play the pope?” he mused.

There is also the fact that Mirren, who won an Oscar for her portrayal of another historical figure in The Queen, is one of the greatest actresses in the world, and has won near-unanimous raves for her performance.

“Helen totally got it in terms of what it means to be Golda, because, also, Golda was American, American-Jewish, and I thought that Helen created the character so beautifully.

“When you have an actress like Helen Mirren, who has so much self-confidence about what she does, she’s so good and she knows she’s good, the approach [to working with her] is easy. She knows how to prepare for this role perfectly, because she’s done this before. She needed my guidance, she needed my point of view, and she said, ‘Don’t be shy about telling me what you think and giving me some comments... it’s teamwork.’ And once she said that to me, it opened something in me.”

Mirren – who would have been out promoting the movie now were it not for the actors’ and writers’ strike in Hollywood – has said in past interviews that she likes to give an interpretation when playing a real person, not an impersonation. Nattiv spoke admiringly of her process.

“Golda was a turtle, not a bunny, she was slow in her movements and she never raised her voice, she never screamed or shouted. So that was one of our decisions, Helen and I, that she keeps it all very quiet. And I wanted all the nuances to be very small, tiny. When we would have these discussions, I would take her aside and say, ‘Just a little smaller, keep it low,’ and she’d say, ‘Fine, fine.’”

When he gave her feedback, she was “always gracious... You can feel her strength, but she never uses it in a toxic way.”

Nattiv went on to give me more examples than there is room for here of her kindness to him, including allowing him to use her personal assistant when she was ill. She was also gracious with the mainly Israeli cast, which included Lior Ashkenazi, Rami Heuberger, and Dvir Benedek, as well as such non-Israelis as Camille Cottin as Lou Kaddar, Meir’s assistant and confidante, and Liev Schreiber as Henry Kissinger.

“She called it ‘my tribe of actors,’ and she said, ‘It’s almost like a company in the theater, when you meet other actors you don’t know but you speak the same language, it’s the language of acting.’ She immediately had a beautiful bond with the Israelis and she said, ‘Part of me loving Israel, is that I love the artists in Israel.’”

She did not balk when he warned her that he would be moving in for extreme close-ups, although she asked why.

“I told her that her dry, wrinkled skin is like a map of the desert, it’s part of the texture of the war, instead of going out into the desert, you are the desert, and she liked this idea... The approach was psychological, and she played it from the inside out.”

She was also on board with his decision to give the movie a feeling of claustrophobia, making the command center, where Meir must weigh the conflicting advice of her military commanders, seem oppressively small and airless. Among his inspirations in creating this stifling atmosphere was the television series Chernobyl as well as 1970s movies The Conversation and Three Days of the Condor.

The little air that there was in the rooms in Golda was filled with smoke, since Meir smoked heavily, even during the treatments for lymphoma she underwent during the war.

“It’s almost like she was killing herself slowly, and every puff of a cigarette makes her skin more wrinkled and more dry, I wanted to get that into the movie.” Noting that almost all the top brass were also heavy smokers, he said, “For me, it’s a metaphor for blindness, for people who can’t see the warnings, who can’t see anything... the smoke in their eyes is a metaphor for the dysfunctional leadership.”

Acknowledging that the movie concerns a time when Israelis were disillusioned with their government, he noted that it was fitting that it was being released at a time when protesters are taking to the streets in large numbers.

“There was a blindness and deafness to reality of the leaders in ’73 and the government today is blind to what is going on,” he said, but noted that whatever you think of Meir’s conduct during the war, “she took responsibility for what she did, unlike the leaders of today, who have no self-criticism. I’ve seen Israelis crying at screenings of the movie, they feel something has been lost.”